Clara Peeters' "Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels" features a subtle self-portrait that only the sharpest eyes can detect. Wikimedia Commons

Clara Peeters' "Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels" features a subtle self-portrait that only the sharpest eyes can detect. Wikimedia CommonsLeaving a lasting legacy through a masterpiece is remarkable, but embedding a clever, hidden nod to your audience elevates that legacy even further. Legendary artists like Leonardo da Vinci often infused their works with symbolism, such as in "The Last Supper, where intricate details have sparked endless scholarly debates. Below, explore six other renowned artworks that contain concealed messages you might not have noticed.

1. Clara Peeters' "Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels" (c. 1615)

"Among my most cherished examples of concealed imagery in art is Clara Peeters' still life, 'Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels,' housed in the Mauritshuis in The Hague," remarks Ross King, a renowned author of works on Italian, French, and Canadian art and history, such as "Leonardo and The Last Supper," "Brunelleschi's Dome," and "Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling."

"Created in the early 17th century, this painting offers a strikingly realistic portrayal of a tempting midday treat. However, upon closer inspection, Peeters has ingeniously inserted her own likeness: her tiny reflection appears on the polished surface of the jug's lid at the center of the composition. While this act may seem humble, it simultaneously showcases her extraordinary talent for miniature detail."

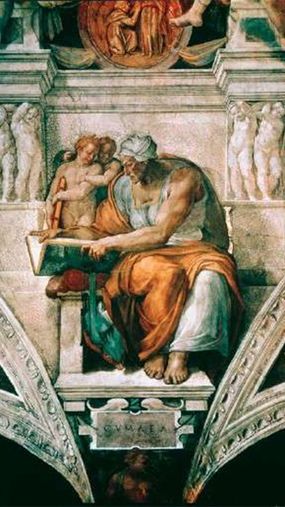

The Sistine Chapel's ceiling is brimming with concealed messages left by Michelangelo.

Wikimedia Commons

The Sistine Chapel's ceiling is brimming with concealed messages left by Michelangelo.

Wikimedia Commons2. Michelangelo's Frescoes on the Vault of the Sistine Chapel (1508-1512)

"Michelangelo portrayed a collection of sibyls and prophets from the Old Testament, each seated on thrones and flanked by angelic figures," explains King.

"One of the two cherubs peering over the muscular shoulder of the Cumaean Sibyl makes an offensive hand gesture, placing his thumb between his index and middle fingers. This gesture, known as mano in fico in Italian, traces back to ancient Roman times and is akin to flipping someone off. While viewers on the chapel floor couldn't see the details, Michelangelo likely took delight in secretly embedding this vulgar sign into his grand work."

Additionally, the Sistine Chapel's ceiling frescoes contain Michelangelo's intricate anatomical sketches, cleverly hidden within the depiction of God's figure. Although Michelangelo destroyed most of his anatomical studies, these detailed drawings remained concealed from Pope Julius II and countless admirers for centuries.

3. Sandro Botticelli's "Primavera" (late 1470s or early 1480s)

A deep understanding of botany might be necessary to fully grasp the intricacies of Sandro Botticelli's masterpiece, often regarded as the "first large-scale canvas produced in Renaissance Florence." Specialists note that the artwork features at least 500 distinct plants, representing over 200 species, many of which are believed to have flourished in Florence during the springtime of the 15th century.

Botticelli's "Primavera" is a treasure trove for botany enthusiasts.

Christophel Fine Art/Getty Images

Botticelli's "Primavera" is a treasure trove for botany enthusiasts.

Christophel Fine Art/Getty Images4. Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" (1503)

While not all art experts concur, Italian researcher Silvano Vinceti claims that Leonardo da Vinci's iconic female portrait harbors hidden secrets within her enigmatic gaze.

As the head of Italy's National Committee for Cultural Heritage, Vinceti and his team analyzed high-resolution images of the painting, proposing that it contains concealed symbols, such as minuscule letters and numbers in the subject's eyes, invisible to the naked eye on the aged original.

They assert that Mona Lisa's right eye features the initials LV, which they interpret as da Vinci's signature, marking his ownership of the masterpiece.

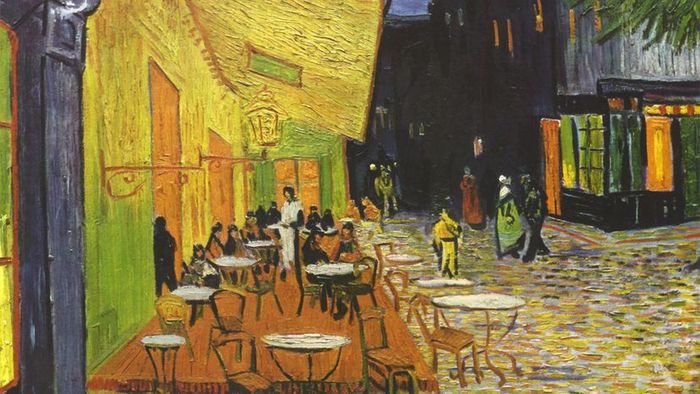

5. Vincent van Gogh's "Café Terrace at Night" (1888)

Returning briefly to "The Last Supper": Beyond da Vinci's iconic depiction, some argue that Vincent van Gogh also subtly referenced the biblical scene in his 19th-century work "Café Terrace at Night," though the connections are understated.

Van Gogh scholar Jared Baxter points out that keen observers can spot a long-haired central figure in the background, encircled by 12 others. Still skeptical? Consider the figure lurking in the shadows, reminiscent of the infamous Judas.

If doubts persist, try locating the small crucifixes scattered across the painting, including one positioned above the Christ-like figure.

Vincent van Gogh reimagined the Last Supper on a café terrace under the night sky in Arles, France.

Wikimedia Commons

Vincent van Gogh reimagined the Last Supper on a café terrace under the night sky in Arles, France.

Wikimedia Commons6. Jan van Eyck's "The Arnolfini Portrait" (1434)

Van Eyck's hidden details are mirrored in the reflection.

Wikimedia Commons

Van Eyck's hidden details are mirrored in the reflection.

Wikimedia CommonsAlthough the primary figures in Jan van Eyck's artwork are believed to be the affluent merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his spouse, Costanza Trenta, they are not the sole individuals depicted.

Upon closer inspection of the mirror positioned at the room's center, two additional figures can be seen entering the space.

Many art historians suggest that one of these figures is van Eyck himself, as evidenced by a Latin inscription above the mirror that reads, "Jan van Eyck was here. 1434," serving as the artist's signature.

A fascinating interpretation arises from the fact that Giovanni's wife passed away in 1433, leading to two possibilities: either van Eyck started the painting while she was alive and completed it after her death, or it was a posthumous tribute. The man's gentle hold on the woman's hand may symbolize her passing, while the chandelier's candles—lit on the man's side and extinguished on the woman's—represent life and death.

Occasionally, artists aren't deliberately concealing elements but are instead rectifying controversial choices. When John Singer Sargent painted wealthy Parisian socialite Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau in 1884, the upper class was reportedly scandalized by a slipping shoulder strap. To address the backlash, Sargent reworked the straps, changed the painting's title to shield the subject's identity, and even retreated to London to escape the ensuing embarrassment.