The practice of novelists incorporating real-life elements into their fiction has sparked ongoing discussions, with some authors vehemently opposing the idea that actual individuals can be authentically portrayed in fictional narratives.

“Writers who depict societal life, whether from an external or internal perspective, are often met with the absurd accusation of inserting ‘real people’—those personally known to the author—into their stories,” Edith Wharton remarked in 1933. “‘Real people’ transplanted into a fictional setting would lose their authenticity; only characters born from the author’s imagination can truly evoke a sense of reality.”

Nevertheless, throughout literary history, there exists a clear pattern of novels that heavily draw on real individuals and events, frequently under the guise of altered identities. Below, we explore six books where authors stirred controversy by fictionalizing real-life occurrences.

1. Glenarvon // Caroline Lamb

Lady Caroline Lamb, a prolific author, is often linked to the poet Lord Byron, with whom she shared a romantic relationship. This connection became particularly evident when she released her novel Glenarvon in 1816. Byron, depicted as the titular character, famously dismissed the book—a fictionalized retelling of his life and their affair—as a crude and sensational publication.

In addition to Byron, the novel was rife with thinly veiled depictions of Lamb’s acquaintances and prominent members of British society. Among them were Elizabeth Vassall Fox, Lady Holland (represented as the Princess of Madagascar), and Holland’s son, Godfrey Vassall Webster (portrayed as William Buchanan), who had once been Lamb’s lover. Lady Holland immediately recognized herself and her son in the narrative and was incensed, remarking, “every flaw, folly, and weakness (including my limited mobility due to illness) is laid bare.”

Much like Lady Holland, others depicted in the novel reacted harshly to their portrayals, and Lamb’s standing in society declined as a consequence. However, the controversy surrounding Glenarvon extended beyond its caricatures of real individuals. As highlighted in the introduction to Glenarvon in The Works of Lady Caroline Lamb Vol. 1, “Lamb situated her story in Ireland during the 1798 uprising for Catholic emancipation, which was met with severe repression. … [The novel] championed the political and military efforts of Irish Catholics, portraying Glenarvon, its Byronic protagonist, as a betrayer of their movement.”

In response to the uproar, Lamb made revisions for the second edition of the novel, adjusting certain aspects: While she retained her depiction of Byron’s counterpart, she altered secondary characters and softened elements deemed offensive, such as replacing the term god with heaven and tempering the explicit nature of the central relationship.

2. The Sun Also Rises // Ernest Hemingway

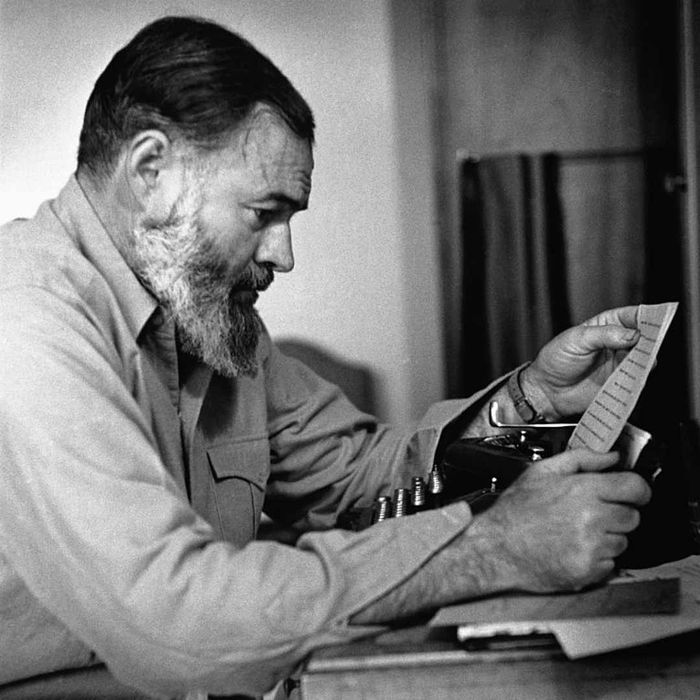

Ernest Hemingway. | Hulton Deutsch/GettyImages

Ernest Hemingway. | Hulton Deutsch/GettyImagesErnest Hemingway’s first novel, The Sun Also Rises, published in 1926, established his reputation as a literary giant. Often hailed as “the finest roman à clef in literature,” the book drew heavily from Hemingway’s own experiences and friendships during his time in Europe in the 1920s. From wild nights of drinking to witnessing bullfights in Spain, their escapades were vividly reimagined in the novel—and that was just the beginning.

Hemingway didn’t just insert himself into the narrative—early drafts referred to the protagonist, Jake Barnes, as “Hem.” Additionally, many of his contemporaries were thinly veiled in the story, their identities barely concealed under altered names. One of the most notable real-life events fictionalized in The Sun Also Rises was the romantic entanglement between Harold Loeb (portrayed as Robert Cohn) and Lady Duff Twysden (as Lady Brett Ashley). Twysden was appalled by the portrayal and later labeled Hemingway as “cruel” for publishing the novel.

Hemingway made his intentions clear one evening after the group returned from Spain: “I’m writing a book,” he informed his friend Kitty Cannell (who would also feature in the novel). “Everyone’s in it.” He revealed that Loeb was meant to be the antagonist. As Lesley M.M. Blume—author of Everybody Behaves Badly, which explores the creation of The Sun Also Rises—noted, “The depictions would torment Lady Duff and the others for the rest of their lives.”

3. Animal Farm // George Orwell

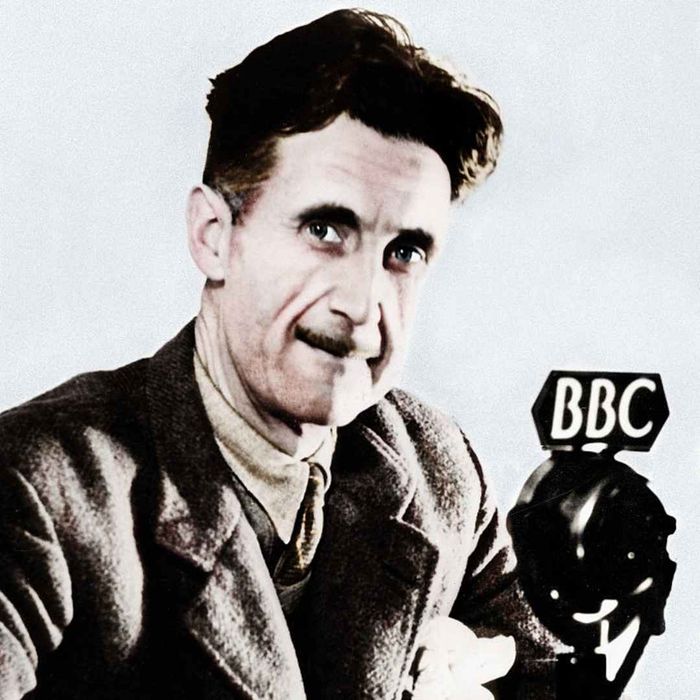

George Orwell. | adoc-photos/GettyImages

George Orwell. | adoc-photos/GettyImagesGeorge Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), one of the most renowned political allegories, reimagines the Russian Revolution and Stalin’s ascent through the lens of “a fairy story” (the book’s subtitle). The animals, humans, and locations in the novel symbolize key figures and events from that historical era. Manor Farm, renamed “Animal Farm” after the animals’ rebellion, represents Russia, with its name change mirroring Russia’s post-revolution transformations. Historical personalities were also recreated: Farmer Jones symbolizes Nicholas II, the last Russian tsar; Napoleon the pig embodies Joseph Stalin; and Snowball, another pig, represents Leon Trotsky.

The creation and release of the book sparked controversy, as many in Britain opposed providing a platform for critiques of Stalin and the Soviet regime—especially since they were wartime allies against Nazi Germany when Orwell was seeking publication. Four publishers, including T.S. Eliot at Faber & Faber, rejected the manuscript before Secker & Warburg accepted it. Despite its success, the book faced bans in several countries, including the Soviet Union, where it remained unpublished until 1988.

4. The Bell Jar // Sylvia Plath

Blue Plaque Commemorating Sylvia Plath. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Blue Plaque Commemorating Sylvia Plath. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesPublished in Britain just before her death in 1963, Sylvia Plath’s sole novel, The Bell Jar, drew heavily from her personal experiences as a young adult, including her stay in a psychiatric facility. Plath kept the novel a secret from her mother, Aurelia, fearing its autobiographical nature might cause issues. The publisher worried about potential libel lawsuits in England, where defendants must prove the truth of their statements. To avoid legal and personal complications, Plath altered details to obscure the real-life parallels, as noted by biographer Carl Rollyson. She further concealed her identity by adopting the pseudonym Victoria Lucas and portraying herself as the fictional Esther Greenwood.

When Plath’s authorship of The Bell Jar was revealed a few years later, Aurelia initially opposed its publication in the U.S.—claiming Plath had never intended for it to be released there. She was also displeased with how characters, whom she believed had genuinely supported Sylvia in real life, were depicted. (The Bell Jar wasn’t published in the U.S. until 1971.)

Despite Plath’s efforts to alter details, it seems they weren’t sufficient: According to writer Joanne Greenberg, a colleague from Plath’s magazine days remarked, “‘She wrote The Bell Jar and exposed all of us … she revealed the abortion one person had and the affair another was involved in. We could never face each other again, as these were secrets we had kept.’” The revelations in The Bell Jar were so explosive that they reportedly caused the dissolution of two marriages.

5. Answered Prayers // Truman Capote

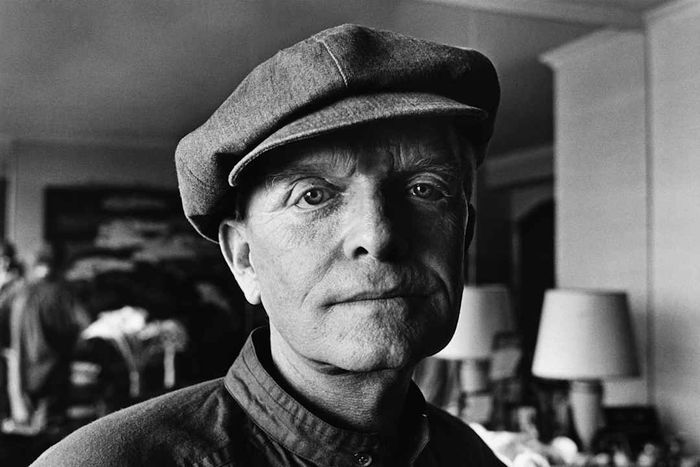

Truman Capote. | George Rose/GettyImages

Truman Capote. | George Rose/GettyImagesStarting in 1958, Truman Capote began teasing a novel inspired by real-life events, which he believed would become his magnum opus. He titled it Answered Prayers. The specifics of the novel remained unclear until 1975, when he released excerpts from the unfinished work in Esquire. The second chapter, titled “La Côte Basque 1965,” ignited a massive controversy.

When his friends and New York’s elite read the chapter, it became evident which real-life events Capote was fictionalizing—and precisely who the thinly veiled characters represented. One of the most scandalous portrayals was that of William Woodward (renamed David Hopkins in the novel) and his wife Ann (who retained her name in the story). In 1955, Ann shot William at home, claiming she mistook him for an intruder, though some suspected it was premeditated. Capote’s version leaned into the latter theory. Ann took her own life shortly before the chapter’s publication, and some speculated it was because she had learned of its contents.

Capote’s social circle ostracized him, and he never completed Answered Prayers. The novel was eventually published posthumously in the 1980s.

6. Black Water // Joyce Carol Oates

Joyce Carol Oates. | Leonardo Cendamo/GettyImages

Joyce Carol Oates. | Leonardo Cendamo/GettyImagesJoyce Carol Oates earned a Pulitzer Prize nomination in Fiction for her 1992 novella Black Water, inspired by a highly contentious real-life incident. In July 1969, Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy left a party with Mary Jo Kopechne—a former aide on his late brother Robert’s presidential campaign—and accidentally drove his car off Dike Bridge, which lacked guardrails, on Chappaquiddick Island. Kennedy managed to escape the vehicle and tried to save Kopechne but was unsuccessful. He delayed reporting the accident until the following day, by which time Kopechne had died. Kennedy later pleaded guilty to leaving the scene and received a suspended sentence.

In Oates’s novella, the Kennedy-like figure is referred to as “The Senator,” while Kopechne is reimagined as Elizabeth Anne Kelleher (nicknamed Kelly). The story unfolds from Kelly’s perspective as she remains trapped in the submerged car, surrounded by the titular black water. Oates shared with The New York Times that she began drafting notes shortly after the incident and revisited the concept during a period when societal attitudes were particularly unfavorable toward women.

Rather than anchoring the story to a specific event, Oates aimed to create a narrative that felt “somewhat mythical,” capturing the archetypal experience of a young woman who places her trust in an older man, only to have it betrayed. She emphasized this approach in her writing process, telling Charlie Rose that she conducted no research. “I wanted to focus on the victim, but there was very little information about her,” she explained. “All the attention was on the senator. That, to me, was part of the tragedy—that the young woman had a story to tell, but she didn’t survive to share it.”