The renowned Japanese author Haruki Murakami is deeply passionate about music. A former jazz club owner, he boasts a collection of over 10,000 vinyl records, hosts his own radio show, and has co-authored a book dedicated entirely to music. “I almost always work listening to music,” he has stated.

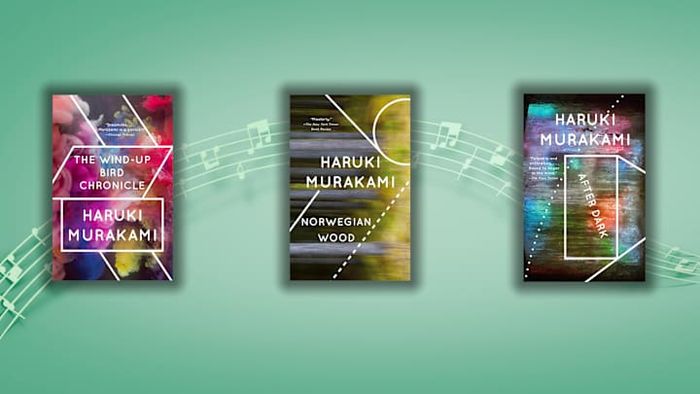

It’s no surprise that music plays a prominent role in Murakami’s novels. His characters are often depicted listening to music, and the songs mentioned frequently offer subtle clues that help navigate the intricate plots. Some of his books even take their titles from songs, though in typical Murakami fashion, the connections aren’t always immediately clear.

1. Hear the Wind Sing

Murakami gained widespread recognition in 1979 with his short novel, Happy Birthday and White Christmas, which was first published in the Japanese literary journal Gunzo. The title references the classic song “White Christmas” by Bing Crosby, a favorite of the novel's unnamed protagonist. In fact, in a sequel to Hear the Wind Sing, Murakami depicts the protagonist playing “White Christmas” on repeat 26 times. However, when Murakami’s novel was published in book form, it was renamed Hear the Wind Sing. Despite this, the original title appears on the cover of various Japanese editions and is even included as a dedication in a novel written by the protagonist’s friend.

2. Norwegian Wood

Murakami’s breakthrough novel, Norwegian Wood, takes its title from the Beatles song of the same name, which is referenced multiple times throughout the story. The song speaks of wood as a material—specifically, cheap wood panelling—but the Japanese title of Murakami’s novel plays on this, using wood as a metaphor for a forest. Forests play an important symbolic role in this and other works by Murakami.

3. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

In Japan, novels are often first serialized or published in volumes, which are later compiled into a single book when translated into English (and sometimes even in Japan). The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, for instance, was originally released as three separate books, which were later combined into one English edition [PDF]. The first of the Japanese books was titled Book of the Thieving Magpie, named after an opera by Gioachino Rossini. Interestingly, Murakami had never heard the full opera before writing the book—only its overture. “I’m convinced he cited Rossini’s overture at the beginning precisely because it’s a piece of music that everybody knows without being able to name or analyse it,” said Jay Rubin, the translator of Murakami’s works, in Murakami Haruki and Our Years of Pilgrimage. “I think Murakami’s drawing a parallel between the half-known music and the existence for most Japanese … of World War II as something that hovers on the edge of consciousness.”

4. After Dark

After Dark is one of Murakami’s more obscure works—a surreal and enigmatic narrative set around the mysterious events of a single night. The title reflects the fact that the entire plot unfolds between dusk and dawn, delving into a shadowy Tokyo that seems like an alternate reality. The name is also a nod to trombonist Curtis Fuller’s track “Five Spot After Dark,” which is a favorite of a pivotal character in the story.

5. Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

Murakami’s 2014 novel takes its title from Franz Liszt’s piano suite, Années de pèlerinage (French for ‘Years of Pilgrimage’). The eighth piece in the first suite, titled “Le mal du pay,” is a recurring theme in the book. It becomes an obsession for the protagonist, who recalls a childhood friend—now deceased—playing this composition on the piano. The piece symbolizes his deep isolation, as he feels cut off from his past and hometown. A secondary character explains that le mal du pay is typically translated as ‘homesickness’ or ‘melancholy,’ but in finer terms, it refers to ‘a groundless sadness that wells up in a person’s heart.’

6. “A Slow Boat to China”

Beyond the novels inspired by songs, Murakami also has a number of short stories in which music serves as the title—one example being “A Slow Boat to China,” named after the 1948 Frank Loesser song, which has been covered by artists ranging from Frank Sinatra to Paul McCartney.

Murakami has long held an interest in China and the painful historical relationship between Japan and China, particularly during Japan’s brutal occupation in the 20th century. His father, who served in the Japanese army during the Second Sino-Japanese War, was deeply scarred by the experience—trauma that Murakami believes was passed down to him. The author has spoken about this guilt, once saying, “History is a collective memory. We have responsibility for our fathers’ generation. We have responsibility for the things our fathers did during the war.”

“A Slow Boat to China” subtly addresses the notion of national shame, examining how a Japanese individual might personally harm a Chinese person, as opposed to doing so through warfare. In idiomatic terms, a slow boat to China suggests something that takes a long time—possibly an allusion to the gradual fading of memories of wartime atrocities or to Japan’s eventual hope for reconciliation and forgiveness.

7. “The 1963/1982 Girl from Ipanema”

In 1982, Murakami wrote a short story titled after the iconic bossa nova song “Girl from Ipanema,” originally by Stan Getz. The author has confessed that, like many of his other works, this story “uses one of [his] favorite pieces of music to evoke a particular mood and time.”

Like much of Murakami’s work, “The 1963/1982 Girl from Ipanema” is a strange tale. In it, he reflects on the fictional girl from Getz’s song, who, because she exists only in the realm of music, has not aged since the song was written. He connects this idea to memories of his high school, where the hallways, in his mind, smell like “mixed salads,” even though there was never a salad bar. This triggers a series of connected, surreal yet humorous thoughts that merge fantasy with memory. Rubin once described it as “vintage Murakami.”

BONUS: South of the Border, West of the Sun and Kafka on the Shore

Murakami doesn’t just borrow real songs for his book titles—sometimes he invents them. South of the Border, West of the Sun takes its name partly from Nat King Cole’s version of the song “South of the Border”… even though Cole never actually recorded it. True to his signature mix of reality and imagination, and his nostalgic yearning for a past that never existed, Murakami creates a fictional song for his characters to listen to. This non-existent tune also appears in another Murakami novel, A Wild Sheep Chase.

In Kafka on the Shore, a boy named Kafka embarks on a bizarre adventure and encounters a variety of characters, one of whom has recorded a song titled “Kafka on the Shore.” This song seems to offer clues for the young protagonist. But is the book’s title inspired by this made-up song, or did the song come first, named after the book? As with all of Murakami’s works, cause and effect blur, and this is no exception. In any case, the song has since been recorded by multiple artists, who have used Murakami’s lyrics to turn his fiction into reality since the book’s 2002 release.