On the evening of April 14, 1912, Violet Jessop was resting in her cabin aboard the Titanic, where she worked as a stewardess. She skimmed through magazines, recited a prayer, and was nearly asleep when a sudden collision startled her awake. Within hours, she found herself adrift in a lifeboat on the icy North Atlantic, among the 705 survivors who witnessed the Titanic vanish into the dark ocean.

Remarkably, Jessop had already endured a maritime disaster before the Titanic, and another would follow. Discover seven astonishing facts about the “unsinkable” Violet Jessop.

1. Violet Jessop took to the seas to provide for her family.

Born in 1887, Jessop was the first child of Irish immigrants in Argentina. Her childhood was fraught with challenges, including the loss of three siblings and her own battle with tuberculosis. After her father's death, her mother moved the family to England and worked as a ship stewardess. However, when her mother fell ill, Violet, at 21, took on the responsibility of supporting her family.

Following in her mother’s footsteps, Jessop became a stewardess for the White Star Line, a leading shipping company transporting both cargo and passengers across the Atlantic. In her role, she catered to first-class passengers, handling tasks like making beds, delivering meals, cleaning, and more. As John Maxtone-Graham, editor of her memoir Titanic Survivor, notes, no service duty was beyond her or her colleagues' responsibilities.

2. She was aboard the RMS 'Olympic' during its collision with another vessel.

In the early 1900s, the White Star Line aimed to dominate the transatlantic passenger market by launching three luxurious ships: the Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic. Despite their grandeur, these ships met with misfortune, and Jessop was present on all three during their respective disasters.

The first incident occurred in September 1911 when the Olympic collided with the HMS Hawke. Although both vessels sustained significant damage, neither sank, and there were no major casualties. Interestingly, Jessop’s memoir omits this event but provides rich accounts of her time aboard the Olympic’s sister ships.

3. She held strong views about the upper-class passengers aboard the 'Titanic'.

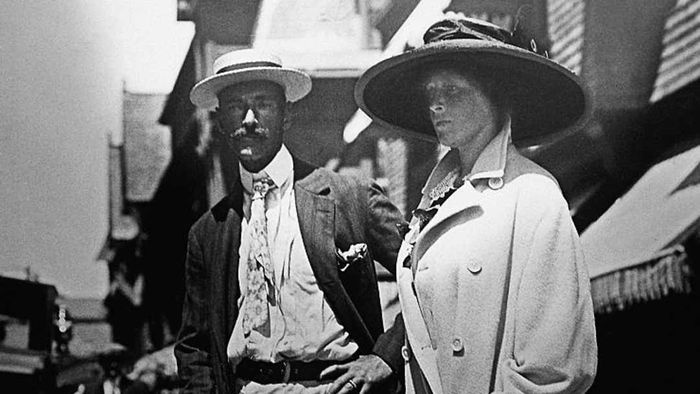

John Jacob Astor IV with his second wife, Madeline Force Astor. | George Rinhart/GettyImages

John Jacob Astor IV with his second wife, Madeline Force Astor. | George Rinhart/GettyImagesDuring her time on the Titanic, Jessop served prominent figures like American financier John Jacob Astor IV and his pregnant wife, Madeleine Force Astor. Their 1911 marriage had sparked controversy due to Astor’s recent divorce and significant age gap with his bride. Jessop described Madeleine as “a quiet, pale, sad-faced, in fact dull young woman” who seemed unenthusiastic, a stark contrast to the vibrant image she had imagined.

Jessop also expressed sharp criticism of other passengers, some of whom may have been fictionalized representations of demanding guests. She recounted how a “Miss Marcia Spatz” arrived with numerous peculiar requests and an abundance of flowers, while a “Miss Townsend” demanded immediate changes to her cabin’s furniture and seemed to delight in watching the crew struggle to accommodate her whims.

4. Following the 'Titanic'’s iceberg collision, Violet Jessop attempted to calm passengers by assuring them everything was under control.

Upon hearing the “horrific grinding crash,” Jessop dressed swiftly and rushed to her designated area. She was soon instructed to guide passengers to the lifeboats. Jessop assisted them with lifebelts, advised them to dress warmly, and encouraged them to gather valuables and blankets. As she moved through the ship, she reassured everyone that these were only precautionary steps, not yet fully grasping the severity of the situation. “Surely the Titanic couldn’t be sinking!” she wrote in her memoir. “She was so flawless, so brand new.”

The grim truth hit Jessop when she noticed the ship’s bow tilting toward the dark ocean as she turned to speak to a colleague. “For a brief moment,” she recalled, “my heart stopped, as it often does when unshakable faith faces its first major blow.”

5. She cared for a baby who had been left behind.

Titanic survivors in lifeboat | Krista Few/GettyImages

Titanic survivors in lifeboat | Krista Few/GettyImagesAs Jessop boarded a lifeboat with other women and children, prioritized as the first to evacuate, a deck officer handed her a baby, whom she described as “somebody’s forgotten baby.” The lifeboat descended to the ocean with a jarring impact, causing the baby to cry. Jessop cradled the child, witnessing the Titanic’s bow dip deeper into the water until the ship split in two and vanished beneath the waves with a deafening roar. Amid the freezing Atlantic, Jessop feared the baby might perish in her arms. She wrapped it in a blanket she had brought from the ship, and the child soon fell asleep.

Hours later, Jessop was rescued by the RMS Carpathia, which had embarked on a heroic mission to save the Titanic survivors. As she stood on the deck, shivering and disoriented, a woman abruptly took the baby from her arms. Jessop later reflected, “I wondered why the mother hadn’t shown even a hint of gratitude for her child’s survival.”

6. She narrowly escaped death during the sinking of the HMHS 'Britannic.'

Reluctantly, Jessop returned to sea after the Titanic disaster, driven by necessity. During World War I, she worked as a nurse aboard the HMHS Britannic, which had been converted into a hospital ship. On November 21, 1916, the ship struck a German mine and began sinking rapidly in the Aegean Sea, putting Jessop in peril once again.

Jessop was instructed to board a lifeboat with her colleagues, but they encountered a horrifying sight upon reaching the water: the ship’s propellers were still churning, pulling passengers and boats toward their deadly blades. Despite her years at sea, Jessop couldn’t swim, yet staying in the boat was equally perilous. Clutching her lifebelt, she leaped into the water. As she surfaced, her head collided with the ship’s keel. “It felt as though my brain was rattling inside my skull,” she later wrote.

Jessop seized a floating lifebelt and held on until a motorboat from the Britannic rescued her. Though she survived this maritime catastrophe, the head injury she sustained caused persistent headaches for years.

7. After retiring from her seafaring career, Violet Jessop took up chicken farming.

Despite her harrowing experiences, Jessop remained in the passenger ship industry. She returned to the White Star Line post-war and later joined the Red Star Line, embarking on five global cruises. After a stint in shore-based clerical work, she resumed her maritime career with the Royal Mail Line, traveling to South America. She retired in 1950 at 63 and settled in the countryside.

In her final years, Jessop embraced a quiet life on land, tending to a lush garden and raising chickens to supplement her income by selling eggs. She passed away in 1971 at the age of 84 due to congestive heart failure.