First published in December 1843, A Christmas Carol was written by Charles Dickens in just six weeks, during which he worked obsessively, taking only brief breaks for long morning walks through London to clear his mind. Less than two weeks after completion, the manuscript was sent to print, and by Christmas Eve, the first 6000 copies had sold out.

Though it was an immediate success, the publication of A Christmas Carol wasn’t without challenges. After a falling out with his publisher, Dickens financed the printing himself to secure all profits. However, his commitment to high-quality paper and expensive leather binding made production costs exorbitant. From the initial 6000 copies sold, he earned a profit of only £230 (around £29,885, or $39,560 today), far less than his expected four to five times that amount. Adding to his financial troubles, the book was pirated by rival publisher Parley’s Illuminated Library two months later. Dickens sued, but Parley’s declared bankruptcy in response, leaving Dickens with a legal bill of £700 (around £90,953/$120,376 today).

Despite its troubled beginning, A Christmas Carol quickly became one of Dickens’ most beloved works, both by readers and the author himself. In fact, Dickens chose A Christmas Carol for his final public reading on March 15, 1870, just three months before his death. But what was it that inspired Dickens to write this iconic story in the first place?

1. A Fundraising Event for Charity

On October 5, 1843, Dickens delivered a speech at a fundraising event at the Manchester Athenaeum, a local organization dedicated to promoting education in the city. At the time, Manchester was renowned as a key player in the Industrial Revolution, but its rapid growth came at a great social cost. It is believed that the harsh utilitarian rules and low wages imposed by factory owners on workers in the city influenced Ebenezer Scrooge’s own stinginess and lack of compassion, as he famously states, “Are there no prisons? … And the Union workhouses? Are they still in operation?”

2. The Town of Malton, North Yorkshire

Just before beginning his work on

3. Charles Smithson

During his stay in Malton, Dickens resided with a friend named Charles Smithson, a solicitor working from offices on Chancery Lane—a place thought to have influenced Dickens’ depiction of Scrooge’s counting-house. The two men had first met more than a decade earlier when Smithson worked at the London branch of his family’s firm, after a friend of Dickens—whom he was acting as guarantor for—joined the business. Their friendship lasted for life, even after Smithson returned to Yorkshire from London.

4. “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton”

Dickens often had characters in his novels narrate their own tales and fables, a practice that began with his debut novel The Pickwick Papers. In this work, Mr. Wardle shares a story titled “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole A Sexton,” about Gabriel Grub, a “miserable, grumpy, and sour” man who encounters goblins on Christmas Eve. These goblins attempt to change his ways by showing him visions of the past and future. Ring any bells … ?

5. “How Mr. Chokepear Keeps a Merry Christmas”

“The Goblins Who Stole A Sexton” may not be the only tale that influenced Dickens. Two years prior, in December 1841, a short story titled “How Mr. Chokepear Keeps A Merry Christmas” was published in the British satirical magazine Punch. Written by Douglas Jerrold, the story details the Christmas Day of a businessman named Tobias Chokepear, who begins with breakfast with his family, then goes to church and enjoys a lavish Christmas feast, followed by “cards, snap-dragon games, quadrilles, country dances, and many other ways to make people eat and drink, sending night into the morning.” Despite the festivities, the story ends with the revelation that a man Tobias had lent money to is now imprisoned for debt, that one of Tobias’s daughters is excluded from the family’s celebration for marrying beneath her, and that while the Chokepear family celebrates inside, “shivering wretches” pass by their door. While Mr. Chokepear doesn’t undergo a Christmas epiphany like Scrooge, it’s likely that Jerrold’s moral tale influenced Dickens in some way, especially since the two were close friends—Dickens served as a pallbearer at Jerrold’s funeral in 1857 and later donated the profits of one of his own short stories to Jerrold’s widow.

6. Washington Irving’s Sketch Book

Washington Irving’s Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., a compilation of essays and short stories, was released over 20 years before A Christmas Carol in 1819. While its most renowned tale is "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," the Sketch Book also features several festive stories that present an idealized vision of Christmas, filled with gifts, decorations, songs, dances, games, and lavish meals. Irving based some of these depictions on his own stay at Aston Hall, a grand Jacobean manor on the outskirts of Birmingham, England. These vivid portrayals are believed to have greatly impacted Dickens' writing. In 1841, two years before publishing A Christmas Carol, Dickens (who was just 8 years old when Sketch Book was first published) wrote to Irving, saying, “I wish to travel with you ... down to Bracebridge Hall.”

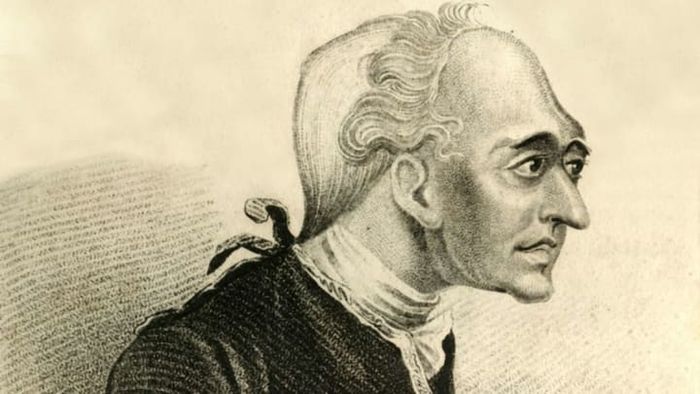

7. John Elwes MP

For the miserly character of Scrooge, Dickens is thought to have drawn inspiration from an infamous 18th-century politician, John Elwes, known for his extreme frugality.

Born in London in 1714, Elwes inherited a fortune when his father passed away when he was just four years old. Then, following the death of his mother—who, despite being wealthy, was so miserly that she is said to have starved herself to death—the entire Elwes estate, valued at approximately £100,000, passed to him. In 1763, Elwes’s uncle, Sir Harvey Elwes, died as well, and his even larger estate—worth over £250,000—was inherited by John.

Although Elwes was immensely wealthy, he prided himself on spending as little as possible. Despite being elected to Parliament in 1772, he reportedly wore rags and looked so ragged that people often mistook him for a beggar and gave him money in the streets. He only saw doctors when absolutely necessary, and once, after severely injuring both his legs, he paid a doctor to treat only one—and bet the doctor that the untreated leg would heal faster (which it did, by two weeks). He allowed his grand estates to fall into ruin due to lack of maintenance, went to bed at sundown to avoid buying candles, and sometimes ate rotten food to save on fresh ingredients (including, allegedly, consuming a dead moorhen pulled from a river by a rat—a story that might be more myth than fact). Despite all this, Elwes left behind an estate worth at least £500,000 when he died in 1789, earning the nickname “Elwes the Miser.”

After Elwes’ death, Edward Topham penned a highly popular biography of him that went through 12 editions over the following years. Topham had his own reasons for telling Elwes’ story; he saw Elwes as “the perfect vanity of unused wealth.”

BONUS: One Person Who was Likely Not an Influence—Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie

According to a popular story, during a trip to Edinburgh in 1841, Dickens took a walk through the Canongate churchyard and noticed a gravestone with the unflattering inscription, “EBENEZER LENNOX SCROGGIE—MEAN MAN.” Dickens later wrote that he imagined this inscription must have “shrivelled” Mr. Scroggie’s soul, thinking it was a terrible mark to carry into eternity, but he still drew inspiration from it for the creation of Ebenezer Scrooge. However, Dickens had misread the inscription. Ebenezer Scroggie, born in Kirkaldy in 1792, was actually a “meal man,” or corn merchant.

Here’s the problem with this tale: It’s likely just that—a tale. A representative from the Edinburgh Civic Trust told Uncle John's Fully Loaded Bathroom Reader that it was an "interesting story, but not necessarily based on fact... [T]here’s no evidence of an Ebenezer Scroggie as a merchant in the post office directories of the period, the gravestone no longer exists, and there’s no parish burial record. I’ve yet to see any direct quote from Dickens on this either."

So where did this myth originate? "I find myself complicit in a probable Dickens hoax," wrote Rowan Pelling in The Telegraph in 2012.

"On Monday, I came across a letter in The Guardian, which claimed to uncover the source of the name Ebenezer Scrooge. The letter described how Dickens 'visited the Canongate churchyard in Edinburgh’s Royal Mile' in 1841 and 'noticed a memorial slab for Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie, a 'meal man' (i.e., a corn merchant).' According to the story, Dickens mistakenly read this as 'mean man' and was struck by the idea that someone could be so miserly that it was etched into a gravestone. In the extended version of this tale, Scroggie is portrayed as a licentious bon viveur. How do I know? I published this literary 'exclusive' in 1997, in The Erotic Review. However, as we went to press, the facts were questioned, and I realized the author, Peter Clarke, was likely pulling my leg. No one could verify the story, but it seemed a shame to let the facts get in the way of a good story. The fame of the Edinburgh merchant grew: in 2010, it was reported that even though Scroggie's gravestone had been removed in the 1930s, plans were underway for a new memorial in honor of the man supposedly inspiring Charles Dickens. I wait with bated breath for the next chapter of this tale."

To explore more about the Christmas stories Charles Dickens wrote after A Christmas Carol, head here.