Long before modern oddities like cursed phone numbers and eerie Kleenex ads, people were wary of ancient cursed books. These mysterious tomes could appear in any genre—while spellbooks and magical texts were obvious suspects, tales of curses have also been linked to novels, encyclopedias, historical accounts, and even poetry anthologies.

Fortunately, cursed books are rare. In 2010, Google estimated that 130 million unique books had been published, a number that has skyrocketed in the past decade. However, when J.W. Ocker was researching for his 2020 book Cursed Objects, he found it challenging to identify books with enough of a cursed reputation to include. “One of my criteria was whether the object had a body count,” Ocker tells Mytour. “And I don’t recall finding any cursed books that met that standard.”

Ocker also points out that many so-called cursed books aren’t truly cursed in the traditional sense. “Most ‘cursed books’ I encountered weren’t actually cursed,” he says. “They were more like supernatural hazards, such as spellbooks. For example, simply owning or touching the book didn’t bring harm or bad luck, as a cursed chair or vase might. Instead, the danger came from attempting to use the spells within.”

Ocker also mentions the curses medieval scribes would inscribe in their meticulously handwritten books, though these were primarily intended to deter theft. There’s no proof these curses ever worked, so they didn’t meet his criteria.

Occasionally, a book gains a notorious reputation. Whether it’s due to a trail of misfortune, a chilling internet legend, or powerful entities attempting to suppress its contents, these books captivate our imagination. From a sinister Bible to a somber Japanese war poem, here are eight texts accused of causing insanity, tragedy, and even death.

1. The Codex Gigas

If a book’s curse potential were determined by its size, the Codex Gigas, also known as the Devil’s Bible, would reign supreme. Weighing 165 pounds and standing three feet tall, this 800-year-old manuscript is considered the largest surviving medieval book. (“Codex Gigas” translates to “giant book.”) While its exact origins remain a mystery, historians suggest it was created between 1204 and 1230 in the Kingdom of Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. The National Library of Sweden notes that the book passed through several monasteries before Emperor Rudolf II acquired it for his private collection (which also included the Voynich Manuscript) in 1594. It was later seized by the Swedish army during the Thirty Years’ War in 1648 and has been housed in Sweden’s National Library since 1768.

Unlike most illuminated manuscripts, which were collaborative efforts, the Codex Gigas is believed to be the work of a single scribe. Written entirely in Latin, the book includes the Old and New Testaments, historical accounts of Czech and Jewish origins, an encyclopedia covering topics like geometry, law, and entertainment, medical texts, hundreds of obituaries, various magic spells, and a calendar.

The Devil as illustrated in the Codex Gigas. | Per B. Adolphson / KB, Swedish National Library

The Devil as illustrated in the Codex Gigas. | Per B. Adolphson / KB, Swedish National LibraryThe book’s eerie reputation is tied to a vivid illustration of the Devil within its pages and a legend explaining its origin. Folklore suggests the manuscript was created by a monk—possibly Hermannus Heremitus, or Herman the Recluse—who had violated his vows and faced execution by being entombed alive. To save himself, he proposed a deal: if he could write a book encompassing all human knowledge in one night, his life would be spared. Realizing the impossibility, the monk allegedly sold his soul to the Devil, who aided him in completing the book and “signed” it with the infamous portrait. (Another version claims the monk added the image as thanks for Satan’s help.)

Several stories of misfortune surround the Codex Gigas, though its curse appears relatively mild for a book supposedly coauthored by Beelzebub. One tale, dating back to at least 1858, recounts a guard who was institutionalized after being accidentally locked inside Sweden’s National Library overnight. He was reportedly discovered under a table the next morning, claiming to have witnessed the Codex Gigas joining a parade of books floating through the air.

2. The Book of Soyga

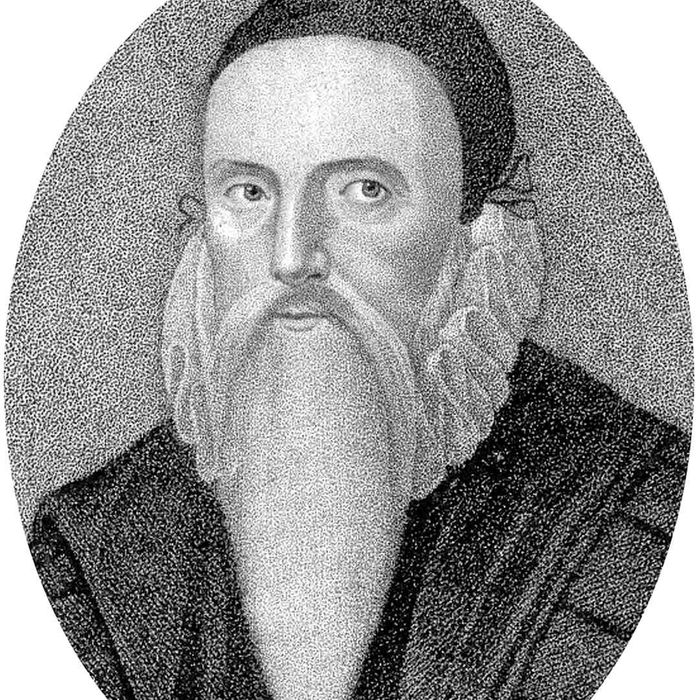

Dr. John Dee (1527-1608), scientist, philosopher, mathematician | Apic/GettyImages

Dr. John Dee (1527-1608), scientist, philosopher, mathematician | Apic/GettyImagesThe Book of Soyga, also known as Aldaraia sive Soyga vocor, is an ancient occult manuscript dating back to the 1500s. Its existence is primarily known through John Dee, a 16th-century polymath whose vast knowledge spanned mathematics, physics, chemistry, and astronomy. Dee, also an avid occultist, was deeply fascinated by angelic communication. The Book of Soyga captivated him, as it contained not only magical incantations and writings on demonology and astrology but also detailed the names and lineages of angels. In his biography The Queen’s Conjurer, Benjamin Woolley notes that Dee believed the book held “an ancient, divine message written in the original language spoken to Adam—the pure, untainted word of God.”

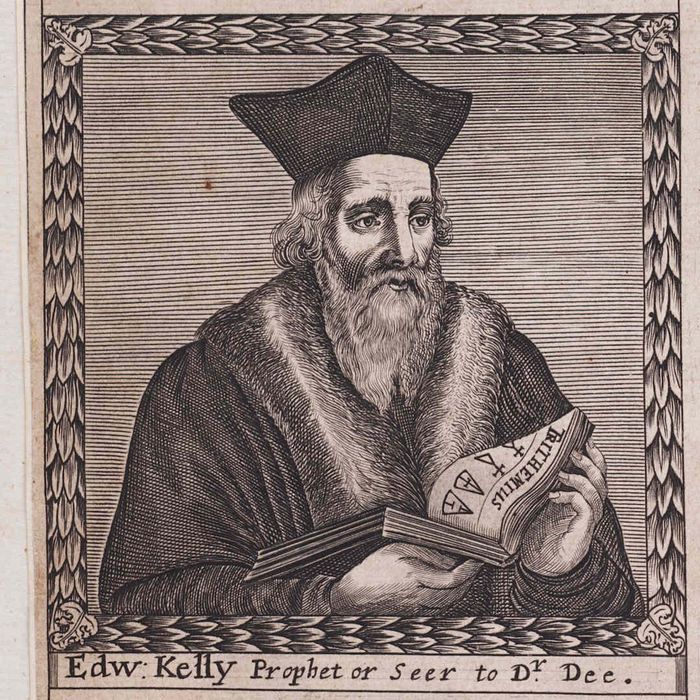

The book also features 36 enigmatic tables that baffled scholars for centuries. Dee sought to decode them with the assistance of Edward Kelley, a scryer who claimed to communicate with angels. (Kelley, who sometimes used aliases like Edward Talbot, had a dubious past, including a conviction for counterfeiting and rumors of having his ears severed as punishment.) According to Sky History, Dee’s desperation to converse with angels led him to agree when Kelley claimed the angels demanded the two men exchange wives as payment for divine messages. Nine months later, Theodore Dee was born.

Edward Kelley (From: The order of the Inspirati), 1659. Artist: Anonymous | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Edward Kelley (From: The order of the Inspirati), 1659. Artist: Anonymous | Heritage Images/GettyImagesWith Kelley acting as an intermediary, Dee contacted the archangel Uriel to inquire if the Book of Soyga was authentic. Uriel, communicating through Kelley, confirmed its legitimacy but stated that only the archangel Michael could decipher the tables. Unfortunately, Michael was unavailable at the time.

This interaction may have contributed to the Book of Soyga’s infamous reputation as a cursed text, sometimes referred to as “the Book that Kills.” During their conversation, Dee mentioned to Uriel that he had been warned he would die within two and a half years if he ever decoded the text. Uriel reassured Dee that he would live for over a century.

However, the book’s cursed reputation is largely unverified. Most references to its malevolent nature come from online sources, with no concrete evidence or documented incidents of misfortune linked to it.

Dee passed away in 1608 at the age of 81. The Book of Soyga exchanged hands several times before disappearing from historical records. Three centuries later, in 1994, Deborah Harkness, who had just completed her doctoral dissertation (“John Dee’s Conversations with Angels”), stumbled upon a reference to Aldaraia sive Soyga in the Bodleian Library’s catalog. Upon examining the book, she realized she had discovered a treasure trove for Dee scholars. This discovery inspired her debut novel, A Discovery of Witches, which became the foundation of a bestselling trilogy and was later adapted into a television series.

In 1998, mathematician Jim Reeds deciphered the code behind the enigmatic tables. Reeds identified a pattern based on the frequency and positioning of specific letters relative to others—or, as he described it, “a letter is derived by counting a certain number of letters after the one directly above it … in the table.” He developed a series of mathematical formulas to decode the tables, each of which was built around a six-letter “code word.” However, the significance of these code words and the intended message of the tables (if any) remain a mystery.

As for the supposed “curse,” it seems to have been ineffective. According to Google Scholar, Reeds was still active in publishing as recently as 2010.

3. The Book of Abramelin

This text may ring a bell for horror enthusiasts—it played a crucial role in the 2016 film festival hit A Dark Song.

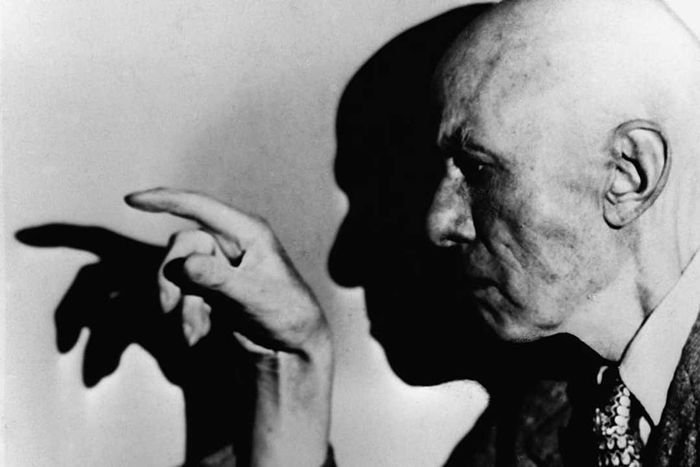

The Book of Abramelin, formally titled The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, is a Jewish mystical text believed to originate from the 14th or 15th century. However, its modern fame stems from the 19th- and 20th-century occultists of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. One of the Order’s founders, S.L.M. Mathers, produced the first English translation in the 1890s, based on a 1750 French manuscript. As noted by writer and occultist Lon Milo DuQuette in his foreword to a 2006 edition, Mathers’s translation gained popularity among his contemporaries, cementing The Book of Abramelin—often referred to simply as “the Abramelin” in occult circles—as a cornerstone of modern occultism. It is said to have influenced Aleister Crowley’s system of “magick.”

Aleister Crowley, English Writer and Magician | Hulton Deutsch/GettyImages

Aleister Crowley, English Writer and Magician | Hulton Deutsch/GettyImagesThe core of the Abramelin revolves around an intricate, months-long ritual designed to help the practitioner connect with their “Holy Guardian Angel”—essentially their divine counterpart. The challenge arises after a three-day phase of “blissful intimacy with the Angel,” as DuQuette describes. Following this, the sorcerer must summon and subdue “every unredeemed spirit of the infernal realms”—essentially, all the demons of hell. While the angel is said to guide the magician through this ordeal, it remains an arduous task. DuQuette suggests that the Abramelin’s cursed reputation may stem from its instructions on defeating “the world’s evil spirits.” These spirits, naturally, would prefer such knowledge to remain hidden, leading to rumors that merely possessing the book could be dangerous.

However, the risk might be justified. Beyond instructions for summoning angels and demons, the Abramelin contains spells for transforming someone into a donkey, conjuring juggling spirit monkeys, and even commanding a spirit to deliver cheese.

4. The Orphan’s Story

Historia del Huérfano, also known as The Orphan’s Story, is a novel authored by a Spanish monk, Martín de León y Cárdenas, between 1608 and 1615. Initially, Martín de León intended to publish the novel in 1621 under the pen name Andrés de León, but the plan fell through. The Guardian suggests he may have withheld publication to protect his reputation within the Roman Catholic Church. (He later became bishop of Trivento in 1630 and archbishop of Palermo in 1650.)

The book was believed lost for centuries until 1965, when a Spanish scholar discovered what is thought to be the sole surviving copy in the New York archives of the Hispanic Society of America. Despite multiple attempts to publish it, none succeeded, fueling rumors of a curse surrounding The Orphan’s Story. The project eventually landed with Belinda Palacios, a Peruvian philologist, who dedicated two years to preparing the manuscript for publication. Shortly after she began editing, warnings about the curse surfaced.

“When I started working on it, many people warned me that the book was cursed and that those who worked on it often died,” Palacios told The Guardian in 2018. In an interview with The Telegraph that same year, she elaborated: “It’s taken so long because previous editors met untimely ends—one from a mysterious illness, another in a car crash, and a third from other causes.” According to the Endless Thread podcast, the victims included Antonio Rodríguez-Moñino, a Spanish scholar who died in 1970, and William C. Bryant, a professor of Spanish.

In 2017—four centuries after its creation—The Orphan’s Story was finally published. Palacios has remained unaffected by the so-called “curse”: She currently teaches Spanish-American Literature at two Swiss universities and published her own novel, Niñagordita, in 2022.

5. The Grand Grimoire

Lucifuge Rofocale | Culture Club/GettyImages

Lucifuge Rofocale | Culture Club/GettyImagesWhile many tales of cursed books can be attributed to coincidence or superstition, others hint at a deeper narrative—one tied to the power of literacy and efforts to deter people from books that challenge established norms.

In his 1898 work The Book of Black Magic and Pacts, British occultist Arthur Edward Waite labels the Grand Grimoire as one of “the four explicit manuals of Black Magic.” The text provides intricate instructions for summoning Lucifugé Rofocale, Satan’s chief lieutenant. Historian Owen Davies notes that the Grand Grimoire is often dated to 1702, though it likely emerged around 1750. It quickly became a publishing phenomenon; in his 2010 book Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, Davies describes it as “the first mass-market grimoire explicitly dedicated to diabolical practices.”

The book’s reputation as dangerous or cursed may stem more from its popularity than its content. In 19th-century France, the Grand Grimoire was among several spell books widely circulated as chapbooks and sold in bookstores. Davies argues that church authorities, fearing these books undermined their influence, launched a campaign to demonize them. Over time, books like the Grand Grimoire were seen as malevolent—even purchasing a copy was considered perilous.

6. The Great Omar

The “Great Omar” was a bespoke edition of quatrains by the 11th-century Persian poet Omar Khayyám, who gained Western fame after Edward FitzGerald translated his verses in 1859. The book remained relatively obscure until 1911, when master bookbinder Francis Sangorski completed an extravagant version commissioned by a London bookstore manager. Sangorski was granted an unlimited budget and two directives: the final product must justify its price and be “the finest modern binding in the world.”

Sangorski spent two years perfecting every detail. To ensure accuracy, he borrowed a human skull for reference and even arranged for a zookeeper to feed a live rat to a snake to observe “the angle of its jaws” during feeding. According to the BBC, he used 100 square feet of gold leaf, 5000 leather pieces, and over 1000 gemstones, including rubies, topazes, and emeralds. Despite its grandeur, the bookshop struggled to sell it, pricing it at £1000 (around $150,000 today). After a failed attempt to sell it in the U.S., the book returned to London and eventually sold at auction to an American buyer for less than half its original price. Tragically, the Great Omar was aboard the Titanic when it sank. Ten weeks later, Sangorski drowned during a family vacation at age 37.

Sangorski’s masterpiece was lost in the Titanic wreck, but a replica was created in the 1930s using his original designs. Bookbinder Stanley Bray completed this version just as World War II began. To protect it from bombings, it was stored in a London vault—ironically, one of the first targets of Nazi air raids. While the safe survived, the book did not: the intense heat melted and charred its leather and paper. Only the gemstones remained intact.

Undeterred, Bray spent 40 years and 4000 hours crafting a third edition of the Great Omar. This version appears to have broken the “curse”: Bray lived to 88, and the third Omar is now securely stored in the British Library.

Some attribute the book’s misfortunes to the trio of jeweled peacocks adorning its cover. According to the Encyclopedia of Superstitions, certain cultures believe peacock feathers are harbingers of bad luck.

7. Written in Blood

Written in Blood was authored by Robert and Nancy Heinl, who spent years deeply involved in Haiti’s political chaos. Published in 1978, Robert Heinl was a retired Marine Corps colonel who had advised the Haitian government on defense. He and his wife, a British journalist, were expelled from Haiti in 1963 amid worsening U.S.-Haiti relations under François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Heinl’s Washington Post obituary states he was declared persona non grata due to policy disagreements with Duvalier, but rumors surrounding the book’s publication suggest a more sinister tale.

According to The Washington Post, Nancy Heinl became so engrossed in voodoo beliefs that Duvalier believed she was a priestess with supernatural abilities. Duvalier died in 1971, years before the book’s release. However, as Vikas Khatri notes in Curses & Jinxes (2007), Duvalier’s widow, Simone, reportedly took issue with the book’s negative portrayal of her late husband and allegedly placed a voodoo curse on it.

The Washington Post recounts that the manuscript was mysteriously lost at the printers, then stolen during transit. When it finally reached the binding stage, the folding machine broke down. The curse seemingly affected the book’s promotion as well: the first reporter assigned to cover it for The Washington Post fell ill with appendicitis. The authors also claimed that all their non-electric clocks stopped working at home.

The Heinls faced more severe misfortunes. Robert was injured when a stage collapsed during a speech, and days later, he was bitten by a dog near their Embassy Row residence. In May 1979, just months after Written in Blood was published, Robert died suddenly of a heart attack while vacationing in the French West Indies. After his death, Nancy reportedly remarked, “There’s a belief that the closer you get to Haiti, the stronger the magic becomes.”

If the Heinls were indeed victims of a voodoo curse, it wasn’t the first time the Duvalier family allegedly used black magic against their enemies. According to the Encyclopedia of U.S. – Latin American Relations, Duvalier claimed that the assassination of John F. Kennedy Jr. in November 1963 resulted from a voodoo curse he placed on Kennedy. This followed Kennedy’s suspension of aid to Haiti in 1962 due to suspicions of financial misconduct by Duvalier.

8. “Tomino’s Hell”

“Tomino’s Hell” was first published in 1919 as part of Sakin, a poetry collection by Japanese poet Saijō Yaso. The poem appears to describe a young boy’s torment in hell, possibly as punishment for an unforgivable sin. However, folklorist Tara A. Devlin suggests that Western readers often miss key cultural nuances, and the poem is more likely an allegory for a young man’s tragic fate on the battlefield during wartime.

The poem’s rise to creepypasta fame began in 1974, when it inspired the film Pastoral: To Die in the Country by avant-garde director Shuji Terayama. Though Terayama lived for nine years after the film’s release, rumors linked his 1983 death to “Tomino’s Hell.” (He actually died of liver disease.) Stories also emerged of a college student who allegedly died after reading the poem. In 2004, author Yomota Inuhiko reportedly warned, “If you read [‘Tomino’s Hell’] aloud, you will face an inescapable terrible fate.” The poem became a staple of “creepypasta”—internet horror stories that spread like urban legends. (“Creepypasta” derives from “copypasta,” referring to text copied and shared repeatedly.)

The notion that “Tomino’s Hell” is cursed appears to have gained more popularity in the West than in Japan, its country of origin. Mytour consulted two Japanese folklore experts—Lindsay Nelson from Meiji University, author of Circulating Fear: Japanese Horror, Fractured Realities, and New Media, and Zack Davisson, author of Kaibyō: The Supernatural Cats of Japan and Yūrei: The Japanese Ghost—but neither could trace the legend’s origins. “It’s quite likely that the idea of it being a ‘cursed poem’ started in the West,” Davisson notes, pointing to the lack of references to the legend in Japanese sources.

Regarding whether the poem has truly fulfilled its supposed curse, Devlin mentions that “some readers have reported feeling unwell while reading it,” though she attributes such reactions to autosuggestion rather than any supernatural cause.