While it's impossible to pinpoint a single novel as the ultimate work of its era, Marcel Proust’s French masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, is widely regarded as the most frequently cited candidate for the early 20th century. The semi-autobiographical narrative spans seven volumes and several thousand pages, chronicling the journey of an unnamed aristocratic narrator who contemplates themes of love, loss, and the essence of memory—often in a cyclical manner. Sensory experiences like sights, sounds, and smells spark memories that shape both the protagonist’s past and present. By the conclusion, both the narrator and reader realize that memory—its reassurances, shortcomings, and emotions—is what truly defines us all. Keep reading for intriguing tidbits about Lost Time’s legacy and history.

1. Proust took the self-publishing route for the first volume.

Order | French Title | English Title | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|

1. | Du côté de chez Swann | Swann’s Way; The Way by Swann’s | 1913 |

2. | À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs | Within a Budding Grove; In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower | 1919 |

3. | Le Côté de Guermantes | The Guermantes Way | 1920 |

4. | Sodome et Gomorrhe | Cities of the Plain; Sodom and Gomorrah | 1921 |

5. | La Prisonnière | The Prisoner; The Captive | 1923 |

6. | Albertine disparue; La Fugitive | The Sweet Cheat Gone; The Fugitive | 1925 |

7. | Le Temps retrouvé | Time Regained; Finding Time Again | 1927 |

Before embarking on Lost Time, Proust had already written essays and short stories for various magazines and newspapers, with some of his stories even compiled into a book titled Pleasures and Days in 1896. However, securing a publisher for the lengthy and meandering first volume of Lost Time proved challenging. Proust initially submitted the manuscript to a prominent publisher named Fasquelle, who recommended so many revisions that Proust ultimately chose to seek alternative options.

The literary magazine La Nouvelle Revue Française rejected Proust’s work in part because they found his writing too aristocratic; meanwhile, Marc Humblot, another potential publisher, considered it excessively long-winded, remarking that he “couldn’t understand why anyone would take thirty pages to describe how one tosses in bed while trying to fall asleep.”

In the end, Proust took matters into his own hands, deciding to finance the project himself and teaming up with a relatively unknown publisher named Bernard Grasset to print the books. When the work was met with praise, writer André Gide, who had originally backed La Nouvelle Revue Française’s rejection, told Proust that it was “the worst mistake they ever made.” Fortunately, the journal later made up for it by publishing the subsequent volumes.

2. The final three volumes were published after Proust's death.

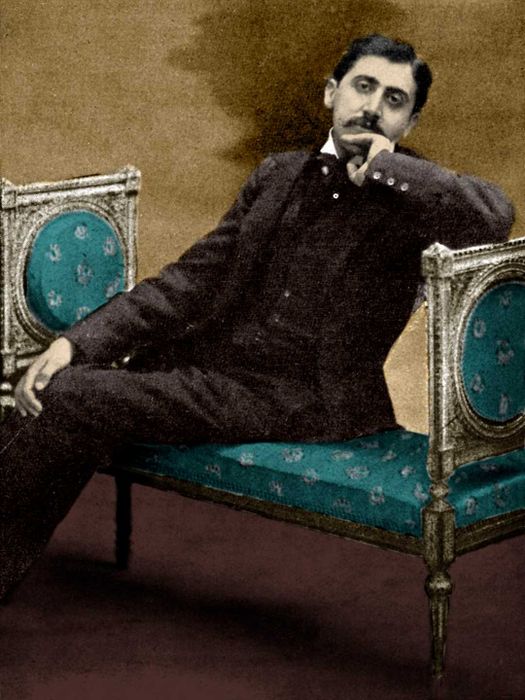

Marcel Proust circa 1900. | Culture Club/GettyImages

Marcel Proust circa 1900. | Culture Club/GettyImagesProust was born into affluence, granting him the freedom to devote himself to writing and engage in the intellectual society of the salon culture. However, frequent asthma attacks interrupted his work, and by the time he sought a publisher for In Search of Lost Time, he felt his time was running out. In a letter, he wrote, “I have put the best of myself into it, and what it needs now is that a monumental tomb should be completed for its reception before my own is filled.”

Proust's prediction proved true: he died from pneumonia in November 1922 at the age of 51, before the last three volumes were published. Although he had finished writing the manuscripts, he hadn't given the final approval; the last volume, Finding Time Again, hadn’t even been typed yet.

“Proust composed through an extraordinarily complex process of writing and revising, blending passages sometimes written years apart, filling the margins with additions, and when the margins ran out, continuing on strips of paper glued to the pages,” scholar Carol Clark wrote in a 2019 article for Literary Hub. “After a time, he would have a clean copy typed, but that did not mark the end of the process; rewriting could continue all the way through to the proof stage and beyond.”

It seems likely that Proust would have continued refining the final three books had he lived longer. Instead, the task of editing fell to his brother, Robert Proust, and French writer Jacques Rivière, who, in Clark’s words, “ironed out a considerable number of inconsistencies and, as they thought, faults of style … to produce a readable text that would appeal to critics and buyers.” Some of these revisions have been undone in later editions as more of Proust’s fragments have emerged. However, we'll never know exactly what Proust would have added or removed from the final proofs.

3. Proust disliked the original English title.

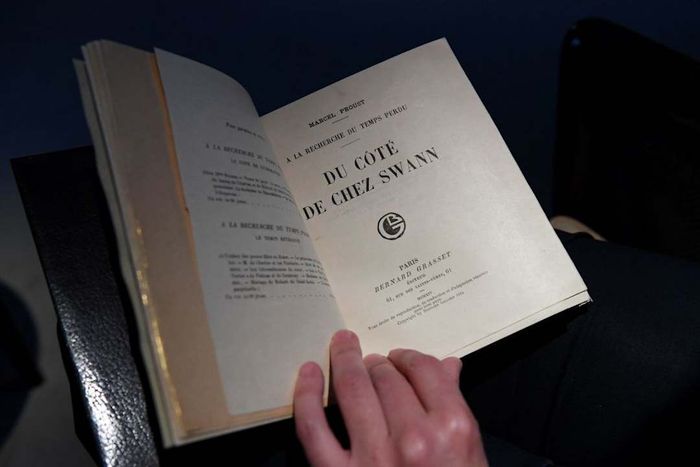

A rare early edition of 'Swann's Way' was auctioned off in 2017. | CHRISTOPHE ARCHAMBAULT/GettyImages

A rare early edition of 'Swann's Way' was auctioned off in 2017. | CHRISTOPHE ARCHAMBAULT/GettyImagesIn Search of Lost Time is a fairly straightforward translation of the original French title: À la recherche du temps perdu. However, when the work first appeared in English, it was titled Remembrance of Things Past. Translator C.K. Scott Moncrieff borrowed this phrase from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30, which opens with: “When to the sessions of sweet silent thought / I summon up remembrance of things past.”

Though Proust expressed deep gratitude to Scott Moncrieff for his translations—he even told him so in a 1922 letter—he couldn’t help but express his disappointment with the title’s inaccuracy, particularly the omission of the term lost time. He also critiqued Scott Moncrieff’s interpretation of the first volume’s title, explaining that Du côté de chez Swann had been changed to Swann’s Way, which led to confusion over the meaning of 'way' as 'manner' instead of 'path.' “By adding to you would have made it all right,” Proust remarked. Scott Moncrieff responded that he was “making my reply to your critiques on another sheet,” but that sheet has unfortunately been lost.

Seventy years later, English publishers replaced Remembrance of Things Past with In Search of Lost Time. (And Du côté de chez Swann is occasionally translated as The Way by Swann’s.)

4. Proust’s iconic madeleine might have been toast instead.

When we first encounter Proust’s narrator in Swann’s Way, he is numbed by routine and inexplicably unable to recall most of his memories. However, everything changes the moment he tastes a tea-soaked madeleine, which triggers a flood of childhood memories. This moment drives the narrative and highlights one of Proust’s key themes: finding significance through memory.

Though Proust based this pivotal scene on a real-life event, the original food wasn’t a madeleine. It was a rusk, a dry, twice-baked biscuit. In 2015, newly published manuscripts revealed that Proust had initially intended the scene to be more faithful to the original moment. In his first draft, the narrator eats a slice of toast with honey; in the second, he bites into a biscotte, or rusk. Imagine if readers had never had the pleasure of reading Proust’s description of a sweet, spongey madeleine as “the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds.”

5. That madeleine moment has been referenced in The Sopranos and Ratatouille.

The madeleine scene is arguably the most famous passage of the entire seven volumes: it even inspired the French term madeleine de Proust, which refers to any sensation that brings a forgotten memory rushing back.

References to Proust's madeleine have also appeared in a few 21st-century Hollywood blockbusters. In Pixar’s Ratatouille (2007), one bite of the titular dish sends fussy food critic Anton Ego spiraling into a memory of his mother’s homemade ratatouille, enjoyed in the rustic, sun-kissed kitchen of his youth. (From then on, not even the shocking discovery that the chef is a literal rat can dampen Ego’s excitement for the restaurant.)

In season 3, episode 3 of The Sopranos, Tony Soprano’s therapist, Dr. Melfi, identifies meat as a Proustian madeleine for Tony. It’s tied to his panic attacks, including his first one as a child, when the family’s meat supply became intertwined with mob-related violence. (“All this from a slice of gabagool?” Tony quips.)

6. Numerous renowned 20th-century writers praised the books …

The influence of In Search of Lost Time on 20th-century writers is hard to overestimate. For instance, Graham Greene called Proust the 'greatest novelist' of the century, while Tennessee Williams remarked that 'No one ever used the material of his life so well' as Proust did.

In The Writing of Fiction, Edith Wharton wrote that Proust’s 'endowment as a novelist—his range of presentation combined with mastery of his instruments—has probably never been surpassed.' Virginia Woolf admired him so much it left her frustrated. 'Proust so titillates my own desire for expression that I can hardly set out the sentence,' she confessed in a 1922 letter. 'Oh if I could write like that! I cry.'

7. … But not everyone was a fan.

Evelyn Waugh in 1943. | Hulton Deutsch/GettyImages

Evelyn Waugh in 1943. | Hulton Deutsch/GettyImagesHowever, not all celebrated authors of the time were exactly lining up to praise Marcel Proust. In a 1948 letter to Nancy Mitford, Evelyn Waugh expressed that he believed Proust had 'absolutely no sense of time.' Meanwhile, D.H. Lawrence harshly criticized Proust—along with James Joyce and Dorothy Richardson—for attempting to extend the life of the 'serious novel' by crafting 'a very long-drawn-out fourteen-volume death-agony.' Joyce, too, failed to recognize any special talent in Proust, though he did humbly admit that he himself was not the most qualified critic.

If you've ever found Proust's prose 'crushingly dull,' you're not alone. Nobel Prize-winning author Kazuo Ishiguro shared a similar sentiment, albeit with one notable exception—Swann’s Way. 'The trouble with Proust is that sometimes you come across an absolutely brilliant passage, but then you have to endure about 200 pages of intense French snobbery, high-society maneuverings, and pure self-indulgence,' Ishiguro told HuffPost in 2015.

8. In Search of Lost Time holds the record as the longest novel ever published.

While In Search of Lost Time is typically divided into seven volumes, it is regarded as a single, cohesive novel—the longest one ever published, according to Guinness World Records. This distinction is based on the total character count, with Proust's masterpiece containing more than 9.6 million characters, including spaces.