The mention of 19th-century Pre-Raphaelite art typically evokes images of radiant, fair-skinned women, often depicted gathering wildflowers. Fanny Eaton, a British art model of Jamaican origin, defied this norm, yet her significant role in this artistic movement has been largely neglected.

Illustrator and writer Sarah Ushurhe recognized this oversight and took action. She produced an animated short film about Eaton, commissioned by the BBC, and even rectified a mislabeled sketch at the Victoria and Albert Museum. “The contributions and presence of Black individuals in British history are rarely emphasized in art history,” Ushurhe shared with Mytour via email. “I’m thrilled that her overlooked career is finally gaining attention—it provides Black and mixed-heritage individuals with representation in non-subservient roles within Victorian art.” Below are eight fascinating facts about Eaton, the often-forgotten Victorian muse.

1. Fanny Eaton was born in 1835, just one year following the abolition of slavery in Britain.

Fanny Matilda Antwistle entered the world on June 23, 1835, in St. Andrew, Jamaica. Her mother, Matilda Foster, was a formerly enslaved individual. While Eaton’s father remains unidentified, historical descriptions labeling her as “mulatto,” a term once derogatorily linked to mules, suggest she was of mixed heritage. Some accounts speculate that James Entwistle, a white British soldier, might have been her father. During the 1840s, Eaton and her mother relocated to England.

2. Simeon Solomon was among the earliest artists to feature Fanny Eaton in his works.

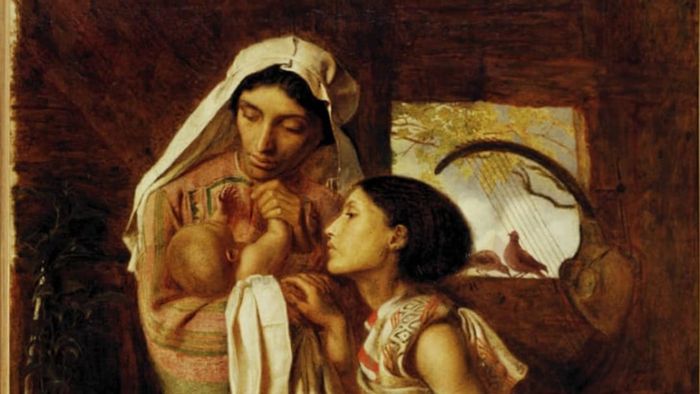

Fanny Eaton portrayed in The Mother of Moses. | Delaware Art Museum, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Fanny Eaton portrayed in The Mother of Moses. | Delaware Art Museum, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainWhile the exact circumstances of their meeting remain unknown, Simeon Solomon drew her in 1859. A year later, she modeled for the lead role in Solomon’s painting The Mother of Moses, which premiered at the Royal Academy in 1860.

3. During Fanny Eaton’s time as an art model, imperialistic ideologies were deeply ingrained in British society.

In 19th-century British art, Black models were frequently employed to emphasize the whiteness or elevate the status of other figures, often depicted as exotic, unnamed characters. This societal context is crucial, as Eaton’s portraits frequently present her as Biblical personas or as elegantly dressed and dignified individuals, despite her working-class background.

4. Fanny Eaton’s natural curly hair is a prominent feature in many of her portraits.

“Though some described her hair as ‘wild,’ her stunning, naturally curly hair, styled with a middle part, has become a defining characteristic in most artworks featuring her,” Ushurhe remarked. Eaton’s curls hold significant relevance today. “Individuals with similar natural hair textures, like myself, who may struggle with self-acceptance, can find inspiration and celebration through Fanny’s representation in art,” Ushurhe added. “This is particularly remarkable for the Victorian era, when Black and mixed-heritage individuals were often marginalized.”

5. Fanny Eaton was immortalized in paintings by two female artists, Rebecca Solomon and Joanna Boyce Wells.

Fanny Eaton depicted in Rebecca Solomon's The Young Teacher. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Fanny Eaton depicted in Rebecca Solomon's The Young Teacher. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe Pre-Raphaelite artists, initially known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, often overshadowed the contributions of women artists associated with the movement, who were frequently seen in relation to their male counterparts. Rebecca Solomon, sister of Simeon Solomon, was one such artist. She portrayed Eaton as an Indian maid in her work A Young Teacher (1861). Another prominent female artist, Joanna Boyce Wells, created one of the most refined and striking studies of Eaton. Wells had intended to paint a portrait of Eaton as a sibyl but passed away at the age of 30 before completing it.

6. After her partner’s death in 1881, Fanny Eaton became the sole provider for their children.

At 22, Fanny Eaton began a life with James Eaton, a horse-cab driver, with whom she had 10 children. Following James’s death in his forties, Fanny took on the responsibility of raising their children alone. Brian Eaton, Fanny’s great-grandson, has speculated that the couple might not have officially married, as no marriage records have been discovered.

7. The exact reason Fanny Eaton ceased modeling remains unclear.

Eaton appears to have ended her modeling career in her mid-thirties, by which time she had six children. After James’s death, she pursued various occupations, including roles as a seamstress, a lodger, and a house cook.

8. The identity of Fanny Eaton in the final painting attributed to her is debated.

Jan Marsh, a Pre-Raphaelite historian and Fanny Eaton expert, suggested on her blog that The Slave, an 1886 painting by William Blake Richmond with a somewhat indistinct appearance, might have used Eaton as the model. Given that Eaton had likely stopped modeling decades before this painting was completed, whether it truly depicts her remains uncertain.