While many polar explorers are celebrated for a single groundbreaking achievement, Roald Amundsen boasts a legacy filled with numerous firsts. This Norwegian legend of the icy frontiers ventured from the South Pole to the North Pole, leaving an indelible mark. Discover eight remarkable highlights from his illustrious career and its poignant conclusion.

1. The adventures of Sir John Franklin sparked Roald Amundsen's passion for polar exploration.

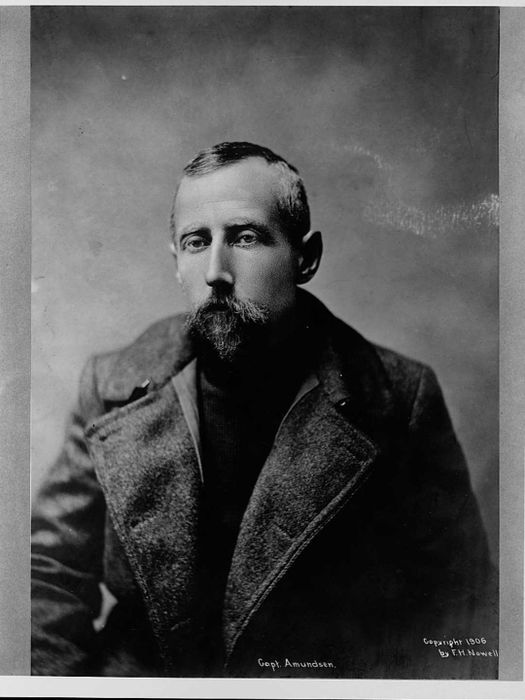

Roald Amundsen during the early 1900s. | Library of Congress/GettyImages

Roald Amundsen during the early 1900s. | Library of Congress/GettyImagesBorn in Borge, Norway, in July 1872, Roald Amundsen was raised in Oslo. He spent his teenage years with his mother after his father’s death at age 14, and his older brothers moved away shortly after. While his mother hoped he would become a doctor, Amundsen had secretly nurtured a passion for polar exploration since he was 15, inspired by the writings of Sir John Franklin, leader of the tragic Franklin expedition.

“What fascinated me most in Sir John’s account was the immense hardships he and his crew endured,” Amundsen wrote in his 1927 autobiography. “A peculiar ambition ignited within me to endure those same trials.”

As a teenager, Amundsen prepared for such challenges by engaging in the two sports available in his community—football (soccer), which he disliked, and skiing, which he loved. He even slept with his windows open during winter, “even in the fiercest cold.” Though he studied medicine to honor his mother’s wishes, her death before his graduation allowed him to leave university “with immense relief” and dedicate himself to exploration.

2. Amundsen was part of the first team to spend a winter in the Antarctic.

The 'Belgica' stuck in ice in 1898. | Bonhams, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The 'Belgica' stuck in ice in 1898. | Bonhams, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainAt 25, Amundsen became the first mate on the Belgica, a Belgian vessel bound for Antarctica in 1897. The ship became trapped in ice for more than a year—from February 1898 to March 1899—marking the first time an expedition endured an entire winter in the Antarctic. The journey was fraught with challenges: Scurvy spread among the crew, and some members suffered from mental breakdowns. (Scientist Emil Racoviță lightened the mood by creating humorous sketches of his fellow crew members.)

Frederick Cook, an American surgeon later known for his controversial claim of reaching the North Pole first, played a crucial role during this ordeal. He combated scurvy by encouraging the crew to consume fresh seal and penguin meat (Amundsen described the latter as “absolutely delicious”). When open water was spotted in early 1899, Cook proposed carving a canal through the ice—a grueling, weeks-long task that ultimately succeeded. The Belgica reached Chile on March 28, 1899, before returning to Europe.

Despite the hardships, the expedition didn’t dampen Amundsen’s passion for polar exploration (and he remained lifelong friends with Cook, despite the latter’s controversies). “These moonlit nights on the ice are a breathtaking sight,” Amundsen wrote in his journal during the voyage. “It’s an extraordinary sensation that captivates you.”

3. He commanded the first expedition to successfully navigate the Northwest Passage …

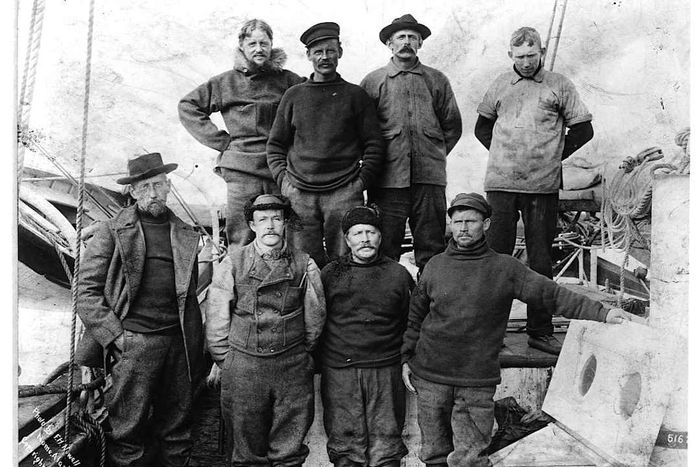

Amundsen (far left) and his team aboard the 'Gjøa' in Nome, Alaska, after completing the Northwest Passage. | Library of Congress/GettyImages

Amundsen (far left) and his team aboard the 'Gjøa' in Nome, Alaska, after completing the Northwest Passage. | Library of Congress/GettyImagesFor centuries, the quest to discover a maritime route through the Canadian Arctic connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans captivated explorers. This pursuit, known as the Northwest Passage, claimed numerous lives, including Sir John Franklin and his 128 men. While Irish explorer Robert McClure technically became the first to traverse the Northwest Passage in 1854 (ironically during a failed rescue mission for Franklin), his journey involved traveling over ice, not solely by ship.

Nearly 50 years later, Amundsen achieved the feat of sailing the entire Northwest Passage. In June 1903, he and six crew members embarked from Europe aboard the 72-foot motorized sloop Gjøa. The journey to the Pacific via the Bering Strait took three years, including two years spent gathering scientific data and learning from Inuit communities near King William Island, followed by another winter waiting for ice to melt near Herschel Island, close to the modern Yukon-Alaska border.

The journey from King William Island to Herschel Island proved to be the most perilous part of the expedition: Amundsen hardly ate or slept as his crew navigated the Gjøa through the shallow Simpson Strait. He described it as “the longest three weeks of my life.” The toll was so apparent that when the Gjøa encountered a whaling ship on the other side, Amundsen mentioned his “age was estimated between 59 and 75 years.” He was only 33.

By the end of summer in 1906, Amundsen and his crew reached Nome, Alaska, to a hero’s welcome. An American steam launch raised the Norwegian flag and escorted them to shore, where “a thunderous cheer erupted from the crowd, and through the night, a sound echoed that moved me deeply, bringing tears to my eyes,” Amundsen wrote. It was the Norwegian national anthem.

4. … And he led the first expedition to successfully reach the South Pole.

Amundsen (left) and Helmer Hanssen at the South Pole. | Illustrated London News/GettyImages

Amundsen (left) and Helmer Hanssen at the South Pole. | Illustrated London News/GettyImagesFor his next endeavor, Amundsen intended to follow the example of fellow Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen by deliberately allowing his ship to become trapped in pack ice, hoping it would carry him to the North Pole. Nansen even lent Amundsen his ship—a lightweight wooden vessel named the Fram (meaning “forward” in Norwegian). However, in September 1909, just before departure, Amundsen discovered that two explorers—his old acquaintance Frederick Cook and another American, Robert Peary—had each claimed to be the first to reach the North Pole.

Realizing the financial benefits of achieving another “first,” Amundsen shifted his focus to the still-unconquered South Pole—without informing most of his crew or anyone in Norway, including Nansen, who had lent him the ship. This decision placed him in direct competition with British explorer Robert Falcon Scott, who had publicly announced his own South Pole expedition. Scott learned of Amundsen’s plans while traveling to Antarctica and even encountered him briefly near their base camps. On October 20, 1911—after establishing supply depots in February 1911, enduring a long winter at the Bay of Whales, and abandoning an initial attempt in September 1911—Amundsen and four companions embarked on a historic journey across the ice using dog sledges and skis.

They raised the Norwegian flag at the South Pole in mid-December, surpassing Scott by about a month. “The worst has happened, or nearly the worst,” Scott wrote upon realizing the Norwegians had already reached the pole. “All our dreams must end; the return will be grueling.” Tragically, Scott and his four-man team died during their return journey.

5. Amundsen attempted, but failed, to tame a polar bear.

Amundsen with Marie in June 1920. | Martin Rønne, National Library of Norway // Public Domain

Amundsen with Marie in June 1920. | Martin Rønne, National Library of Norway // Public DomainDuring the late 1910s and early 1920s, Amundsen embarked on a successful journey through the Northeast Passage aboard his ship Maud, a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via northern Eurasia. The expedition was fraught with challenges: Amundsen endured a broken arm, carbon monoxide poisoning, and a near-fatal encounter with a polar bear while his arm was still recovering.

This wasn’t his only polar bear encounter: In April 1920, a Siberian trader offered him a cub, which Amundsen named Marie and attempted to train. “It’s not easy to befriend Marie, but it might happen,” he wrote. He fed her lard (which she adored), took her on leashed walks (which she disliked), and tried to get her accustomed to being petted and carried. However, Amundsen soon realized that domesticating a rapidly growing wild animal was beyond his abilities. “[When] I brought her milk in the morning, she charged at me in a fury. A skilled trainer might have succeeded, but I had to give up,” he wrote on June 17. That same day, he euthanized her using chloroform.

Amundsen had Marie preserved through taxidermy, and she is now exhibited in the study of his home in Uranienborg, Norway.

6. He adopted two Indigenous foster daughters.

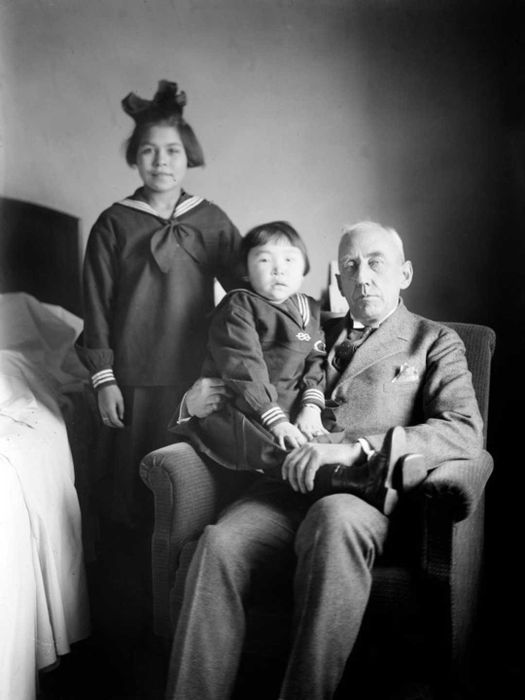

Roald Amundsen with Camilla and Kakonita circa 1922. | Apic/GettyImages

Roald Amundsen with Camilla and Kakonita circa 1922. | Apic/GettyImagesWhile navigating the Northeast Passage, Amundsen and his crew spent considerable time with the Chukchi, an Indigenous Siberian community. Several Chukchi individuals worked on Amundsen’s ship, including Kakot, a widower who brought his sickly 4-year-old daughter, Kakonita (Nita for short).

Nita captivated Amundsen as he helped her recover; he called her “mischievous but utterly delightful” and cherished her calling him “Grandpa.” When Kakot appeared close to remarrying, Amundsen chose to adopt Nita. “I care for her deeply and don’t want her subjected to a stepmother,” he wrote. It’s unclear whether Kakot consented to this arrangement.

Before returning to Norway, Amundsen recruited Camilla Carpendale—the roughly 11-year-old daughter of a Chukchi woman and an Australian trader—to keep Nita company. Camilla’s father consented partly because Amundsen promised to educate his daughter, which he fulfilled. “Despite his demanding life as an explorer, he adored children, often played with us, and always ensured our well-being,” Nita told the Edmonton Journal in 1943.

Ultimately, Amundsen’s attempt at fatherhood ended in failure. While he was often away, the girls were cared for by his two brothers and their families. When he went bankrupt in 1924, his brother Gustav sent the girls—alone—to the U.S., where they spent time in a San Francisco orphanage before eventually reuniting with Camilla’s family, who took them in. Both Camilla and Nita later settled in Canada with their own families.

7. He participated in what might have been the first flight over the North Pole.

In the mid-1920s, Amundsen shifted his focus from polar exploration by sea to the skies. In 1925, he joined a team that set a record for the northernmost point reached by aircraft (87°44’ North). This flight was by seaplane, but his most famous aerial journey occurred the following year aboard the dirigible Norge.

On May 11, 1926, Amundsen and over a dozen others departed Svalbard in the Norge. The team included Italian aviator Umberto Nobile, the dirigible’s engineer and pilot; American explorer Lincoln Ellsworth, who funded the expedition; and Oscar Wisting, a trusted member of Amundsen’s earlier voyages on the Maud and Fram. Three days later, they landed in Teller, Alaska, achieving their goal of crossing the Arctic Ocean. They also flew directly over the North Pole, dropping national flags to commemorate the event. (Amundsen sarcastically remarked that the Norge resembled “a circus wagon of the skies” as Nobile tossed “armfuls” of Italian flags overboard. The two men had a strained relationship.)

The Norge expedition has a credible claim to being the first to cross the North Pole. The claims of Peary, Cook, and Richard E. Byrd, who flew over the pole just days before the Norge, are all heavily disputed. At the very least, Amundsen and his team achieved the first undisputed crossing.

8. Amundsen vanished in 1928.

Roald Amundsen's Latham 47 seaplane shortly before its (and his) disappearance. | Anders Beer Wilse, Norsk Folkemuseum // Public Domain

Roald Amundsen's Latham 47 seaplane shortly before its (and his) disappearance. | Anders Beer Wilse, Norsk Folkemuseum // Public DomainIn late spring 1928, Amundsen led a rescue operation to find Nobile’s airship Italia, which had vanished over the Arctic Ocean. He and a small team left Tromsø, Norway, on June 18 aboard a French seaplane prototype, the Latham 47.02. They were never seen or heard from again.

On August 31, a fishing boat near Tromsø discovered a damaged float from the Latham; additional debris washed up along the Norwegian coast in the following months. Numerous theories circulate about the rescuers’ fate, the most far-fetched suggesting Ellsworth saved Amundsen, who then lived incognito in Mexico. The most plausible explanation is that the entire crew died during or after a crash.

For what it’s worth, this was precisely how Amundsen wished to meet his end—he expressed this sentiment in an interview just weeks before the Latham’s departure: “Ah! If only you understood how magnificent it is up there! That’s where I want to die; I hope death comes to me nobly, while I’m fulfilling a grand mission, swiftly and without pain.”