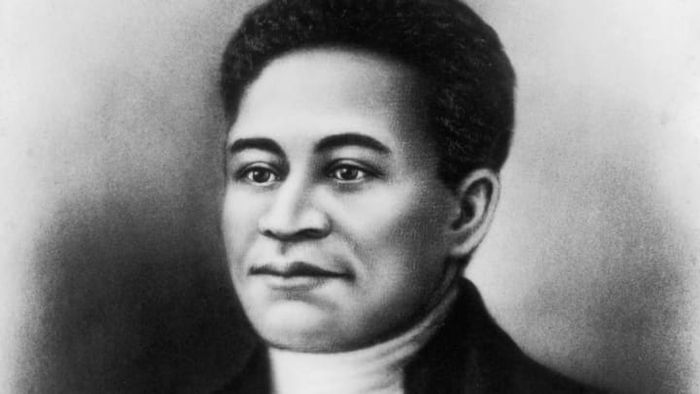

Crispus Attucks holds the distinction of being the first casualty of the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, earning him the title of the inaugural martyr in America's struggle for freedom. In a tribute to the event, poet John Boyle O'Reilly wrote, "Call it riot or revolution, or mob or crowd, as you may, such deaths have been seed of nations." Attucks symbolized the first seed of a burgeoning nation.

1. Crispus Attucks might have fled from slavery.

Little is known about Attucks's early years. Historian Mitch Kachun, in his book First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory, suggests Attucks was born around 1723 in Framingham, Massachusetts. Post-Boston Massacre reports identified him as "a Molatto." His father, Prince Yonger, was an enslaved African, and his mother, Nancy Attucks, is believed to have had Natick or Wampanoag ancestry.

Attucks might have been enslaved before fleeing in 1750. That year, the Boston Gazette published an ad offering 10 pounds for the capture of "'a Molatto fellow, about 27 Years of Age, named Crispas,' who 'ran away from his Master, William Brown, of Framingham,'" as noted by Kachun. The ad described "Crispas" as "'6 Feet two Inches high, [with] short curl'd hair, his Knees nearer together than common.'"

2. Crispus Attucks pursued a career as a whaler.

Attucks is believed to have worked as a harpooner aboard a Nantucket whaling vessel, using the alias "Michael Johnson" to evade recapture into slavery. (A newspaper covering the massacre referred to him as a "mulatto man named Johnson" [PDF].) At the time of the massacre, Attucks was temporarily in Massachusetts, having recently returned from the Bahamas and preparing to depart for North Carolina.

3. Crispus Attucks entered Boston during a period of unrest.

The Stamp Act of 1765 imposed taxes on paper goods, including playing cards, magazines, and stationery, imported into the British colonies. Colonists, angered by taxation without representation, frequently rioted. The Townshend Acts of 1767, which expanded taxation, further fueled their discontent. The Sons of Liberty, a clandestine group of American businessmen, orchestrated a yearlong boycott of British goods. To suppress the rebellion, the British deployed thousands of troops to Boston, a city of 15,000. Tensions peaked just days before the Boston Massacre, when a violent clash erupted between British soldiers and local ropemakers.

4. A disagreement over a barber's bill ignited the Boston Massacre.

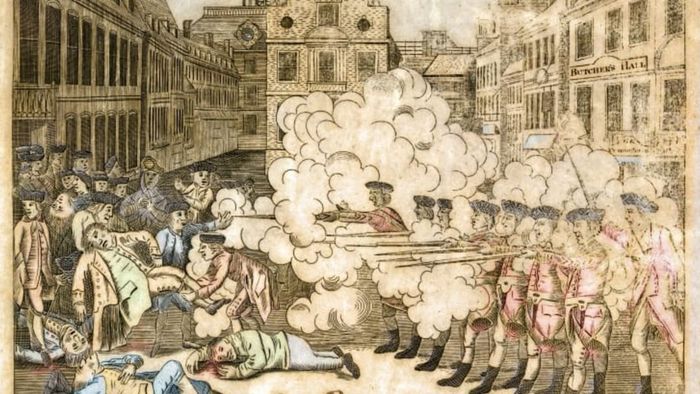

Detail of "The Bloody Massacre" by Paul Revere | Paul Revere, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Detail of "The Bloody Massacre" by Paul Revere | Paul Revere, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainOn March 5, 1770, a young boy accused a British officer of refusing to pay his barber bill. (The officer denied the claim.) When a British sentry confronted the boy, a group of colonists—including Attucks—assembled at Boston's Dock Square and retaliated by taunting the officer. British reinforcements arrived, escalating tensions. The colonists hurled snowballs, stones, and wooden objects at the soldiers. Gunfire erupted, leaving six colonists injured and five dead. Attucks is thought to have been the first casualty.

5. The exact actions of Crispus Attucks during the confrontation remain unclear.

Some accounts suggest Attucks was the primary agitator, striking soldiers with a wooden club, while others claim he was merely an observer, leaning on a stick. Despite the uncertainty, two bullets struck Attucks in the chest, causing instant death.

6. Crispus Attucks's funeral drew a massive crowd of mourners.

Attucks and the four other victims—Samuel Gray, James Caldwell, Samuel Maverick, and Patrick Carr—were laid to rest at Boston's Granary Burying Ground. The funeral procession saw an unprecedented turnout of up to 10,000 people. As one observer wrote, "A larger gathering had never been seen on this continent for such an occasion."

7. John Adams labeled Crispus Attucks as the catalyst for the massacre.

Facing potential execution, the British soldiers were defended by John Adams, who later became America's second president. Adams argued that the soldiers acted in self-defense, describing the protestors as "a disorderly crowd of insolent boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues, and foreign sailors. I see no reason to hesitate in calling such a group a mob, unless the term is too dignified for them." Adams singled out Attucks as the main provocateur. His defense succeeded: no one was found guilty of murder. (Two soldiers, however, were convicted of manslaughter and branded on their thumbs with the letter M.)

8. Crispus Attucks was later celebrated as a symbol of patriotic heroism.

The Boston Massacre monument honors Crispus Attucks and the four other victims. | Scott D, Flickr // CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Boston Massacre monument honors Crispus Attucks and the four other victims. | Scott D, Flickr // CC BY-NC-ND 2.0The public outrage following the massacre compelled British troops to temporarily leave Boston and cost Adams half of his legal clients. Three weeks later, Paul Revere created and distributed a print of the event, which the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History describes as "likely the most influential piece of war propaganda in American history." Boston observed March 5 as a day of remembrance. According to abolitionist and historian William Wells Brown, "The anniversary was marked annually in Boston with speeches and ceremonies until Independence Day replaced it." Over a century later, in 1888, a grand monument was erected at Boston Common to honor Attucks and the four other victims. Today, the monument and the massacre site are key stops on Boston's Freedom Trail.