Reaching Antarctica is no easy feat; one must journey through thousands of miles of icy, treacherous seas, and upon arrival, the conditions are even more extreme. This continent is the coldest, driest, most isolated, windiest, and highest of all Earth's continents. With no trees, rivers, or cities, and only a limited range of life forms, Antarctica remains a mysterious and unexplored place. In fact, NASA suggests that we have more data on the surface of Mars than we do on some parts of Antarctica. Conquering this forbidding landscape requires immense courage, even with today's advanced tools and resources. However, at the turn of the century, it took an extraordinary type of explorer with unparalleled bravery to take on this challenge. Below is a list of the ten most resilient souls who braved the harsh conditions of the South Pole.

8. Sir Edmund Hillary

Famous for being the first to conquer the summit of Mt. Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary also embarked on several Antarctic expeditions. In 1958, he led the New Zealand team of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition. His team was the first to reach the pole since Scott's team in 1912, making him the third person ever to reach it. In the 1970s, Hillary also narrated various sightseeing flights over Antarctica and helped establish the Marble Point runway in 1957. His personal experiences of the continent’s many dangers remain a vital resource for those planning to visit Antarctica. His extraordinary achievements earned him the honor of being featured on New Zealand’s $5 note, both during his lifetime and after.

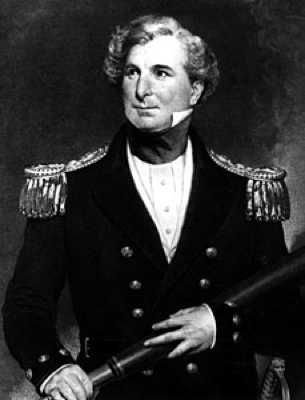

7. Sir James Clark Ross

In the 19th century, while many explorers, whalers, and sealers were aware of Antarctica, its isolation and the perilous waters surrounding it caused the continent to remain largely overlooked. However, Sir James Clark Ross saw its value and, between 1839 and 1843, he led two ships—the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror—further south than anyone before him. By navigating the vast coastlines of Antarctica, Ross may have been the first to confirm that the land was indeed a continent, rather than just a series of islands. He also discovered the Victoria Barrier, a colossal ice shelf that was subsequently named in his honor. Upon returning to England, Ross was knighted and published his account, “A Voyage of Discovery and Research to Southern and Antarctic Regions,” which included one of the earliest recorded uses of the term “Antarctica” to describe the southern continent.

6. Nobu Shirase

While much of history remembers the heroic race to the South Pole between Scott and Amundsen in 1911, fewer recall the Japanese navy’s expedition around the same time. Nobu Shirase and his crew were the first to set foot on the Edward VII Peninsula in 1911, traveling as far as 80°05’S—a remarkable feat for such a small team. Shirase’s seven-man crew explored the southern Alexandra Range before harsh weather conditions forced them to return to their ship. One of the most notable moments in this journey was an unexpected meeting with the Fram, one of Roland Amundsen’s ships, which was waiting for Amundsen’s return from the pole. At one point, Shirase’s expedition had to make an unscheduled stop to winter in Sidney, Australia, where they were aided by fellow explorer Sir Edgeworth David (number 5 on the list). As a gesture of thanks, Shirase presented a 17th-century Samurai sword, which is now displayed in a Sydney museum.

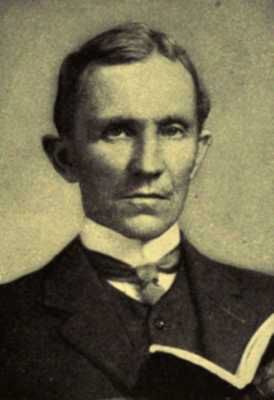

5. Sir Edgeworth David

There’s some confusion, but it’s important to note that there are two south poles. The geographic South Pole marks the absolute southernmost point of the Earth, which is the one most people refer to when they speak of the ‘South Pole.’ The second is the magnetic South Pole, which in 1909 was located at 72°25’S 155°16’E, a few hundred miles away from the geographic pole. Sir Edgeworth David, a Welsh Australian coal magnate and geologist, was part of the first team to attempt to reach the magnetic South Pole. During their journey, he and his crew survived on a diet of seals and penguins while exploring the southern coasts.

David was also the first person to summit Mount Erebus, Antarctica’s only active volcano. It certainly takes courage not just to travel to Antarctica but to climb an active volcano while there. David later joined Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition, where they successfully found the magnetic South Pole in 1909. For this achievement, he was awarded the Muller Medal by the Australian Association for the Advancement of Science.

4. Richard Evelyn Byrd

In 1929, when aviation was still in its early stages, US Naval officer Richard Evelyn Byrd, who was also a pilot and photographer, flew a fragile Ford Tri-motor aircraft and became one of the first individuals to fly over the South Pole. Due to the continent’s extreme altitude and the Trans-Antarctic Mountain range obstructing their path, the crew had to jettison much of their supplies and equipment to lighten the load, barely managing to clear the mountain peaks.

This risk meant that if the aircraft encountered fuel shortages or mechanical issues, there would be no possibility of reaching the other side of the continent on foot. Remarkably, this occurred just over a year after Charles Lindbergh’s famous transatlantic flight. Byrd would go on to lead four additional expeditions to Antarctica, becoming one of the first individuals to ‘winter over’ on the continent, where the unyielding darkness and an average temperature of -70°F (-50°C) make survival almost impossible.

3. Ernest Shackleton

Though Shackleton’s achievements might seem overshadowed by those who reached the pole, historians consider his and his crew’s journey one of the most extraordinary adventures ever recorded. Shackleton’s earlier expeditions included the first journey to the southern magnetic pole and the mapping of a route through the Trans-Antarctic Mountains, which would later be used by Scott on his own southward journey. With the pole already conquered, Shackleton set his sights on the ambitious goal of crossing the entire continent from coast to coast.

Tragically, Shackleton’s quest came to an abrupt end when his ship, ironically named the HMS Endurance, became trapped in pack ice and was eventually crushed, leaving the crew stranded on nearby Elephant Island. For nearly a year, the men survived on a diet of seal, penguin, and whale meat, using seal blubber to fuel fires and stay warm. In one famous photograph, the crew is seen playing soccer on the ice shelf. Shackleton realized they couldn’t survive in this manner indefinitely, and thus made the bold decision to use the remaining lifeboats to attempt a perilous voyage to a whaling station on South Georgia Island, 800 miles away. With little food, water, or medical supplies, Shackleton and five of his men set out across the ice-filled seas.

After weeks at sea, they landed on South Georgia Island, severely weakened by hunger and dehydration. Unfortunately, they had arrived on the uninhabited southern coast, meaning Shackleton and his team had to cross an uncharted mountain range—a feat no one had ever attempted before. Upon reaching the whaling station, Shackleton immediately began organizing an expedition to rescue his crew. Nearly a year and a half after being stranded in Antarctica, Shackleton’s crew was finally rescued by relief ships, bringing them back home. While his trans-Antarctic expedition was a failure as a journey, it was an undeniable triumph for human perseverance and spirit.

2. Roald Amundsen

Amundsen is often regarded as one of the most renowned polar explorers in history, holding the rare distinction of being the first person to reach both the North and South Poles during his lifetime. Unlike Scott’s ill-fated expedition, which faced numerous setbacks, Amundsen’s journey to the South Pole was relatively trouble-free. His use of sturdy sled dogs instead of Scott’s more vulnerable Norwegian ponies, coupled with his efficient management of resources, contributed to his success. However, the expedition was still an arduous and grueling challenge.

Amundsen and his team traversed hundreds of miles through rugged and uncharted mountainous terrain before reaching the South Pole on December 14th, 1911, where they planted their flag and named the region ‘Polheim’, meaning ‘Land of the Pole’. Despite having no animosity toward his polar rival Scott, Amundsen left a note for him, which read:

Dear Captain Scott — As you are likely to be the first to reach this area after us, I kindly ask you to forward this letter to King Haakon VII. Please feel free to use any of the items left in the tent if they may be of assistance. The sledge outside might also be of use to you. Wishing you a safe return.

Yours sincerely, Roald Amundsen.

Although Amundsen led only one expedition to the South Pole, he continued his explorations for the rest of his life until he mysteriously vanished near Bear Island during a rescue mission.

1. Robert Falcon Scott

In the grand scheme of reaching the South Pole, finishing second carries no disgrace. Robert Falcon Scott’s initial expedition to Antarctica took place in 1901, but due to the crew’s lack of experience and inadequate supplies, the mission had to be rescued by relief ships. While it was still considered a success, Scott’s bold claim that he would be the first to reach the South Pole came as a surprise, especially since his first trip barely ended in survival. Determined to succeed, he meticulously planned his next expedition. During preparations, he received a telegram from Amundsen in Melbourne, informing Scott that he intended to be the first at the pole. Scott, however, refused to treat the journey as a race. Confident in his more familiar route, he stuck to his schedule without trying to outpace the Norwegian.

For his final push to the pole, Scott selected five men. When they finally reached the South Pole, they discovered Amundsen had already been there a month earlier. On the return journey, a fierce blizzard struck the men while they were crossing the Ross Ice Shelf, and a combination of scurvy, dehydration, and hypothermia led to their demise. Aware of their fate, the men wrote letters to their families. A simple monument now marks their bravery at Observation Point, where a wooden cross bearing the names of the lost men stands, engraved with a line from Tennyson’s ‘Ulysses’: “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”