Driven by financial motives or sheer excitement, art forgers throughout history have crafted counterfeit masterpieces, replicated originals with precision, and invented entirely new works mimicking renowned artists. These fraudulent creations are so widespread that Vienna, Austria, houses a dedicated Museum of Art Fakes, showcasing countless deceptive pieces. Among the most infamous examples are a forged Vermeer that fooled a Nazi and a counterfeit sculpture falsely credited to Michelangelo.

The Faun

The faun once attributed to Paul Gauguin. | Carlos E. Restrepo, Wikimedia // CC BY 3.0

The faun once attributed to Paul Gauguin. | Carlos E. Restrepo, Wikimedia // CC BY 3.0For a decade, an 18.5-inch ceramic faun sculpture, believed to be by French artist Paul Gauguin, was a celebrated piece at the Chicago Art Institute. However, in 2007, it was exposed as one of numerous forgeries crafted and sold by the Greenhalgh family from northern England—arguably one of the most infamous art forgery families in history.

Shaun, the son, was the creator of the sculptures, while his parents, George and Olive, handled the sales. The family produced an astonishing variety of counterfeit works, complete with fabricated documents like letters and sales receipts to establish false provenance. Among their other notable forgeries were the 10th-century Eadred Reliquary, which they tried to sell to Manchester University, an ancient Egyptian statue known as the Amarna Princess that ended up in the Bolton Museum, and a Roman silver tray called the Risley Park Lanx, acquired by the British Museum. Often, the Greenhalghs replicated lost artifacts that could plausibly reappear at auctions or in private collections. Shaun based his faun sculpture on a sketch from Gauguin’s 1800s notebook, using the genuine illustration to create a piece that seemed authentic. Technical analyses by the museum initially raised no suspicions.

Although police estimated the family earned approximately $1.6 million from their fraudulent activities, they lived modestly in public housing in Bolton, an industrial town. Shaun produced his counterfeit masterpieces in a garden shed. Their downfall began when they offered three Assyrian reliefs to the British Museum around 2005. Experts spotted historical inconsistencies, prompting the museum to contact Scotland Yard. After nearly two decades of forgery, the Greenhalghs were finally caught. Shaun was sentenced to four years and eight months in prison, while his elderly parents received suspended or deferred sentences. After his release in 2010, Shaun claimed that some of his forgeries remained undetected, still deceiving the art world.

Sleeping Eros

A bronze statue from ancient Greece showing Eros asleep, of the kind that could have inspired Michelangelo. | The Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public Domain

A bronze statue from ancient Greece showing Eros asleep, of the kind that could have inspired Michelangelo. | The Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public DomainBefore rising to fame as a Renaissance sculptor, Michelangelo dabbled in art forgery. At just 21 years old in 1496, he crafted a marble figure of a sleeping cupid, deliberately aged to resemble the highly sought-after ancient Roman statues. Known as Sleeping Eros, this counterfeit piece was sold by art dealer Baldassarre del Milanese to Cardinal Raffaele Riario. (Some accounts suggest the dealer further aged the sculpture by burying it in his vineyard.)

Upon discovering the forgery, Cardinal Riario returned the statue but chose not to pursue legal action against the gifted young artist. Instead of tarnishing Michelangelo’s reputation, the act of deception bolstered it. The cardinal went on to commission more works from the Florentine sculptor. As for Sleeping Eros, it was eventually lost and is believed to have been destroyed in a 1698 fire at London’s Whitehall Palace.

The Marienkirche Frescoes

During the bombing of Lübeck, Germany, on March 29, 1942, the historic Marienkirche church was engulfed in flames. As the fire consumed the building, plaster crumbled from the walls, revealing long-hidden Gothic frescoes. This remarkable discovery amid the devastation was dubbed “the miracle of Marienkirche” and was temporarily shielded by makeshift roofing. However, by the war’s conclusion, the paintings were severely damaged. Lothar Malskat, who aided restorer Dietrich Fey in the conservation efforts, later revealed that almost no original paint remained, stating, “even that turned to dust when I blew on it.”

Despite this, the frescoes were declared fully restored by 1951. The public hailed them as symbols of postwar recovery, and commemorative stamps were issued. Few questioned how the colors remained so vivid or how such intricate details survived the bombings and exposure. However, eight months later, Malskat—bitter that Fey had taken all the credit—came forward and confessed that he had painted the frescoes himself. He admitted to using 1930s Austrian actress Hansi Knoteck as the model for the Virgin Mary, his father as a prophet, Rasputin as another figure, and even a brick to age the artwork artificially. Both Malskat and Fey were arrested and sentenced to prison. Further investigations uncovered other forgeries by Malskat, including works mimicking Marc Chagall and Matisse. Some of the frescoes were eventually covered with plaster, while others reportedly remain visible in the church.

The Rospigliosi Cup

A replica of the Rospigliosi cup, previously attributed to Benvenuto Cellini. | Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public Domain

A replica of the Rospigliosi cup, previously attributed to Benvenuto Cellini. | Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public DomainIn the late 1970s, a study of a collection of a thousand drawings by 19th-century German goldsmith Reinhold Vasters sent shockwaves through the museum community. Although these works had been housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum since Vasters’s death in 1909, they had not been closely examined until scholars took a renewed interest. Upon closer inspection, they discovered that many of the designs matched pieces believed to be from the Renaissance, including items at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. By 1984, it was confirmed that at least 45 of the Met’s European jewelry and artifacts were centuries younger than previously thought. Among these was the renowned Rospigliosi Cup, once credited to 16th-century Italian goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini.

As Philippe de Montebello, the Met’s director at the time, explained to The New York Times, “It’s likely that every major collection of Renaissance jewelry, metalwork, and mounted crystals will discover that a significant portion of their items are from the 19th century, not the 16th or 17th.” Further research suggested that Viennese collector Frederic Spitzer, who had commissioned Vasters to create Renaissance-style pieces, may have been responsible for selling them as genuine antiques. The Rospigliosi Cup is still displayed at the Met, but it is now labeled as a skillful 19th-century replica.

Vase de Fleurs (Lilas)

In 2000, an unusual incident occurred at two leading auction houses. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s featured the same painting in their spring catalogs: Paul Gauguin’s 1885 Vase de Fleurs (Lilas). The auction houses quickly consulted a Gauguin expert, who determined that Christie’s version was a forgery. Interestingly, both paintings were linked to New York art dealer Ely Sakhai.

As Sakhai later admitted in his guilty plea, he specialized in acquiring lesser-known but authentic works by artists such as Gauguin, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, Paul Klee, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He then hired Chinese immigrant artists to create exact replicas, complete with imperfections on the canvas backs and forged certificates of authenticity. Sakhai typically sold the copies in Asia and the originals in Europe and the U.S., hoping the two would never cross paths. When they eventually did, Sakhai was sentenced to 41 months in prison and ordered to pay $12.5 million in restitution to the defrauded collectors.

Han van Meegeren’s Vermeers

Han van Meegeren at work, 1945. | GaHetNa (Nationaal Archief NL), Wikimedia

Han van Meegeren at work, 1945. | GaHetNa (Nationaal Archief NL), WikimediaAfter World War II, the Allied Art Commission began the arduous process of recovering art stolen by the Nazis. Among the works in Hermann Göring’s collection, they discovered a previously unknown painting attributed to Dutch master Johannes Vermeer. The commission traced its sale to Han van Meegeren, a Dutch artist and dealer. However, van Meegeren refused to disclose the painting’s original owner prior to its Nazi acquisition, leading to his arrest on charges of treason.

Han van Meegeren faced a dilemma. To avoid the severe charge of treason, he had to confess to a long history of art forgery. Over several years, he had made millions from his counterfeit works. This deception stemmed from his struggles as an artist, as critics dismissed his Rembrandt-inspired portraits for lacking originality.

His first Vermeer—Christ at Emmaus—employed pigments that appeared authentic, but the scene itself was entirely original. He also incorporated Bakelite to give the canvas the texture of an aged painting, then baked it in a pizza oven. In 1937, a leading authority on Dutch art hailed it as “a previously unknown masterpiece by a great artist […] And what a masterpiece!” Van Meegeren’s success wasn’t due to perfectly replicating Vermeer’s style; he imitated it just enough and capitalized on the prevailing belief that Vermeer had a religious phase, which this new work seemed to confirm. He created six more forgeries, including Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery, which Göring acquired. Van Meegeren spent his earnings on champagne and hotels, hiding the rest of his fortune in his garden and beneath the floors of his growing number of properties.

After six weeks in prison, he finally confessed to his jailers, “You think I sold a priceless Vermeer to Göring? There was no Vermeer. I painted it myself.” Initially, no one believed him. To prove his claim, he painted another Vermeer in front of reporters and court-appointed witnesses. He was ultimately sentenced to one year in prison but died before serving his term. By then, he had become a Dutch folk hero for deceiving the Nazis.

Mary Todd Lincoln Portrait

For over 30 years, a portrait believed to depict Mary Todd Lincoln adorned the Illinois governor’s mansion. Attributed to renowned 19th-century painter Francis Bicknell Carpenter, it came with a poignant backstory: it was said to be a surprise gift for President Abraham Lincoln, commissioned by his wife in 1864. However, before she could present it, Lincoln was assassinated.

In 2012, an art restorer discovered that the signature had been added after the painting was completed. In reality, the portrait did not depict Mary Todd Lincoln but an unidentified woman. The New York Times, which had covered the painting’s “discovery” in 1929, revealed that it was part of a scam orchestrated by a man named Ludwig Pflum. He allegedly altered the painting’s features, including adding a brooch with Lincoln’s image, to sell it to Lincoln’s family. The family donated it to the state’s historical library in the 1970s, and it later found its way to the governor’s mansion.

Flower Portrait of William Shakespeare

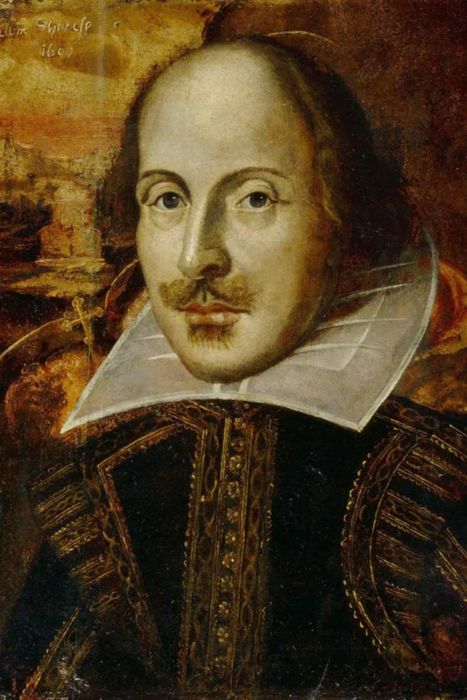

The Flower Portrait of Shakespeare | Wikimedia // Public Domain

The Flower Portrait of Shakespeare | Wikimedia // Public DomainA portrait of William Shakespeare, dated 1609, was once widely regarded as a rare depiction of the playwright created during his lifetime. However, a 2005 investigation by art experts at London’s National Portrait Gallery revealed that the oil painting on wood panel was actually from the early 19th century.

Known as the Flower Portrait after Sir Desmond Flower, who donated it to the Royal Shakespeare Company, it frequently appeared in books and publications of Shakespeare’s works over the past century. Experts now believe the portrait, featuring a wide-eyed Shakespeare in a large white collar, was based on the Droeshout portrait from the 1623 first folio of Shakespeare’s works. Previously, it was thought that the Flower Portrait inspired the Droeshout engraving, a posthumous depiction of Shakespeare. A key clue to the forgery was the presence of chrome yellow in the paint, a pigment not available until the early 1800s.