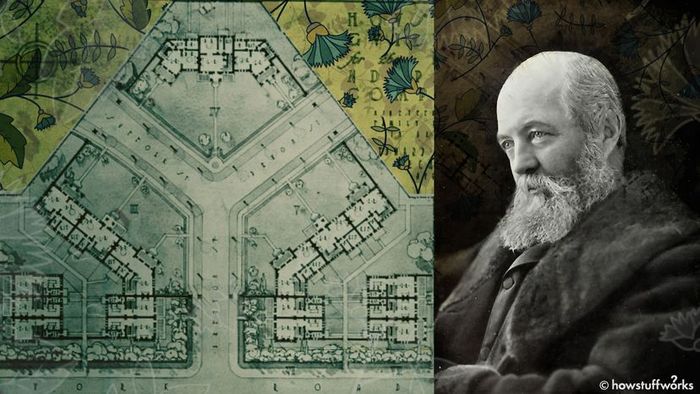

American architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham described Frederick Law Olmsted as someone who 'paints with lakes and wooded slopes....' — MPI/Stringer/Getty Images/Mytour

American architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham described Frederick Law Olmsted as someone who 'paints with lakes and wooded slopes....' — MPI/Stringer/Getty Images/MytourAlthough best known for his creation of New York City's Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was a Connecticut native whose landscape architecture firm designed countless beautiful spaces across the United States. These included parks, parkways, recreation areas, campuses, planned communities, cemeteries, and specialized landscapes for arboreta and expositions. A late bloomer, Olmsted had a diverse career, working as a merchant, apprentice seaman, publisher, experimental farmer, author, public administrator, and mine manager, before finding his true calling at 43. In 1865, he devoted himself fully to landscape architecture, nearly a decade after co-designing Central Park.

"Frederick Law Olmsted was an innovator, author, public official, city planner, and 'Father of Landscape Architecture,' whose extraordinary designs have dramatically shaped the American landscape," says Anne Neal Petri, president and CEO of the National Association for Olmsted Parks, in an email interview. "While his physical landscapes are an impressive legacy, the principles behind them are equally significant. Olmsted recognized that the thoughtful design and planning of parks and public spaces can have profound social, environmental, economic, and health impacts on individuals and communities."

Previously the domain of the affluent, Olmsted believed that public parks and civic spaces should be 'democratic spaces' accessible to all Americans. "He believed that well-designed and properly maintained parks have the power to unite and strengthen communities by offering a place of rest and renewal for everyone, regardless of their social status, wealth, or ethnicity," says Petri. "Long before scientific studies validated his beliefs, he understood how parks could enhance public health by reconnecting people with nature."

"In many respects, he was a social reformer, recognizing that the landscape could promote mental and physical well-being during a time when cities were polluted, overcrowded, and unhealthy," Petri continues. "He referred to parks as the 'lungs of the city' because they were designed to be revitalizing spaces for urban dwellers. Long before Richard Louv coined the term 'nature deficit disorder,' Olmsted understood the importance of reconnecting people with nature, especially as urbanization increased. Remarkably, doctors of his time began prescribing walks in Central Park as a form of therapy. This was exactly what Olmsted had envisioned."

Over the course of his career, Olmsted designed 100 public parks and recreational areas, and together with his successor firms, they created more than 1,090 public parks and parkway systems over a span of 100 years. "Quite remarkable!" says Petri. Here’s a look at eight of his most famous parks, plus one lesser-known gem you might not be familiar with.

1. Central Park, New York City

In 1857, a young architect from London, Calvert Vaux, invited Olmsted to join him in submitting a design for the Central Park competition. At the time, Olmsted was serving as the first superintendent of the park, a position Vaux believed would give Olmsted valuable insights into the park's topography. "Olmsted had never designed a public park before, but their entry, known as the 'Greensward Plan,' was remarkable for its originality and beauty," says Petri. "As many of us do, Olmsted and Vaux worked tirelessly right up until the deadline. The Frederick Law Olmsted Papers note that when they arrived to submit their plan, the office was closed, so they had to wake the janitor and leave their submission with him."

Their proposal was, in fact, inspired. It featured before-and-after views that helped the commissioners visualize the park's transformation after Olmsted and Vaux completed their work. "The plan included open spaces as well as more rugged areas," says Petri. "Both Olmsted and Vaux, anticipating New York City's future growth into a sprawling metropolis, designed the park with dense planting around its edges to block the noise and sights of the future city, creating a calm and restorative space for visitors."

One of Central Park's many water features, providing a serene oasis in the heart of New York City.

Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

One of Central Park's many water features, providing a serene oasis in the heart of New York City.

Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images2. Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York

Designed by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the mid-1800s, Prospect Park spans 585 acres (237 hectares) and opened in 1867, though it was only partially completed at that time. In 1975, the park was designated a scenic landmark by the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission. Today, Prospect Park, affectionately called "Brooklyn's Backyard," attracts over 10 million visitors annually to enjoy its band shell concerts, zoo, playgrounds, pedal boats on the picturesque lake, and miles of roads for joggers, walkers, and cyclists. The park showcases Olmsted's pastoral style, particularly evident in the stunning 75-acre (30-hectare) Long Meadow. "It’s a vast open space," says Petri, "with small bodies of water, scattered trees, and groves, designed to soothe the eye and rejuvenate the spirit."

Prospect Park, located in Brooklyn, New York.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Prospect Park, located in Brooklyn, New York.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)3. Emerald Necklace, Boston

The Emerald Necklace is a series of green spaces that wind through the city of Boston, including the Arnold Arboretum, Franklin Park, and Back Bay Fens. Each of these "jewels" in the necklace offers its own unique, natural landscape, designed to provide a tranquil escape from the noise and chaos of urban life. Spanning 7 miles (11 kilometers) of meadows, marshes, and roads, Olmsted's vision is evident as you walk through this serene network of parks. After successfully applying this idea to Central Park in New York, Olmsted was invited to Boston in the 1870s to design not just one large park, but an entire system that would offer a peaceful retreat for residents to enjoy after a long day. By 1895, after two decades of work, Olmsted completed the system. He later moved to Brookline in 1883, where he opened the country’s first landscape architecture firm and continued to shape Boston’s parks.

Lilac Sunday at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Lilac Sunday at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)4. Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North Carolina

The 3-mile (5-kilometer) Approach Road leading from Biltmore Village to the Biltmore House in Asheville, North Carolina, was carefully designed by Olmsted to seamlessly integrate the forest with the landscape. The design intentionally avoids hard edges and long-range views. As Parker Andes, the director of horticulture, notes on the Biltmore website, this road serves as the first garden and landscape feature visitors encounter upon arriving, offering them a glimpse into Olmsted's expertise. The road was planted with native species as a foundation, enhanced by 10,000 rhododendrons to form the backdrop. Olmsted also incorporated mountain laurels, native and Japanese andromedas, and a variety of other plants. He added evergreens in the foreground for richness and mystery, while introducing tropical elements like river cane and bamboo. To ensure color in winter, Olmsted selected hardy olives, junipers, yews, and red cedars, all contributing to the light and shadow interplay that defines the picturesque style of the estate.

Autumn at Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Autumn at Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)5. Mount Royal, Montreal, Canada

The creation of Montreal's Mount Royal began in 1874, marking Olmsted's first project after parting ways with Vaux. To emphasize the area's natural mountainous features, Olmsted aimed to enhance the mountain's appearance by strategically placing vegetation. For example, he planned to plant dense shade trees along the base of the mountain's carriage path to create a valley effect, which would become more pronounced as the path ascended. The vegetation would thin out as visitors climbed higher, completing the illusion of an exaggerated elevation. While Olmsted envisioned a grand mountain pasture with a lake, the city opted for a reservoir instead, and Olmsted proposed a grand promenade around it. However, due to Montreal's economic downturn in the 1870s, many of Olmsted's original designs were abandoned. Although the carriage road was constructed, it was done hastily, without regard to Olmsted's intended vegetation choices, and the reservoir was never built.

Mount Royal Park in Montreal, Canada.

Needpix

Mount Royal Park in Montreal, Canada.

Needpix6. The Grounds of the U.S. Capitol and White House

"For almost two decades, Olmsted directed the development of the Capitol Grounds," says Petri. "In 1874, Congress assigned Olmsted the task of designing and overseeing improvements to the landscape. It was Olmsted who infused the Capitol Grounds with a sense of dignity, enhancing the Capitol's architectural splendor." Olmsted's original vision called for a master plan that would link the White House, the Capitol, and other government buildings to represent the unity of the nation. However, he had to scale back his ambitious plans, with only the 50 acres (20 hectares) of the Capitol grounds available for development.

Unable to design a park within the Capitol's confines — due to 21 streets bordering the grounds and 46 entrances for pedestrians and vehicles — he chose instead to craft a scenic arrangement that showcased the Capitol's grandeur from locations where the entire structure could be admired. Olmsted received just $1,500 for his initial design of the grounds. In addition, he was given a budget to cover travel costs, wages for his team, and a significant $200,000 for improvements to the Capitol grounds. During his 18-year tenure as the Capitol's landscape architect, Olmsted worked to create a setting where the Capitol's architectural magnificence stood at the forefront, with the grounds' natural beauty providing comfort and respite for visitors without overshadowing the Capitol's sightlines.

7. Washington Park, Chicago

The Washington Park lily pond in the 1890s.

Wikimedia Commons

The Washington Park lily pond in the 1890s.

Wikimedia CommonsThis potential National Historic Landmark is regarded as one of Olmsted's finest "country parks." Located in Chicago's South Park System, it is the only park system in the Midwest designed by Olmsted and his famous collaborator, Calvert Vaux. Olmsted first advocated for a park and boulevard system in Chicago during his visit to the city in the Civil War era. In February 1869, the Illinois State Legislature passed three bills that led to the creation of a park and boulevard network for Chicago. This legislation gave rise to the South Park Commission and brought Olmsted and Vaux on board. The newly formed commission selected 1,055 acres (427 hectares) of land — larger than both Central and Prospect Parks — situated 6 miles (10 kilometers) south of downtown for the park, along with boulevards linking it to downtown and the West Park System.

Initially called South Park, the area was divided into eastern and western sections: Jackson Park, a 593-acre (240-hectare) lakefront area; Washington Park, a 372-acre (150-hectare) inland stretch of prairie land; and the Midway Plaisance, a 90-acre (36-hectare) five-block linear boulevard connecting the two parks. The commissioners hired Olmsted and Vaux to draft the original plan for South Park, publishing it in 1871, just before the Great Chicago Fire. The park's design featured a greensward, expansive meadows, and rolling hills. Washington Park was built according to Olmsted's vision, and by the late 1880s, around two-thirds of it had been completed under the guidance of another prominent landscape architect, H.W.S. Cleveland.

8. The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago

Olmsted was responsible for designing the landscape for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. "Many people are familiar with the Exposition thanks to the bestselling book by Erik Larsen, The Devil in the White City," says Petri. "It was called 'White City' because the fair showcased a large number of white buildings hosting Exposition exhibitions. Faced with the imposing architecture, Olmsted used the landscape to soften the visual experience and connect city residents with nature's refreshing and restorative qualities." At the conclusion of the Exposition in 1895, Olmsted and his son, John Charles, returned to refine the landscape — now free of the Exposition structures. Their final design ensured that the Science and Industry Building was the tallest and only structure on the lakeshore, preventing it from dominating the landscape. Their goal was to guarantee that Jackson Park would provide an exceptional and unspoiled natural experience for future generations.

9. And Now for One You Might Not Have Heard About: Olmsted Linear Park, Atlanta, Georgia

In 1890, Atlanta entrepreneur Joel Hurt hired Olmsted to develop a plan for the area now known as Druid Hills. Olmsted's firm submitted a preliminary design in 1893, which laid the foundation for the six-segment Linear Park. The final plan was completed in 1905, two years after Olmsted's death, and the firm continued its involvement until 1908, when the Druid Hills Corporation acquired the property. The park was then developed under the direction of Coca-Cola magnate Asa G. Candler and became the model for future developments in Atlanta. In the 1980s, the Georgia Department of Transportation proposed a four-lane highway that would have bisected Olmsted Linear Park. Concerned citizens rallied to stop the project, preserving both the historic neighborhoods and the park.

Olmsted Linear Park winds through the Druid Hills neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Olmsted Linear Park winds through the Druid Hills neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)The year 2022 marks the 200th anniversary of Frederick Law Olmsted's birth. To commemorate the bicentennial, the National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP) is leading a coalition of 10 national organizations in launching the Olmsted 200 campaign. This initiative will feature year-long celebrations aimed at raising awareness about Olmsted's life, legacy, and values, while also garnering public and policy support for America's natural and historic spaces. For more details on the campaign and how to get involved in national and local events, visit www.naop.org.