In Scotland, marking the New Year is a monumental occasion: While they embrace worldwide traditions such as dazzling fireworks and exchanging kisses at midnight, they also infuse the festivities with their own distinctive rituals. Known as Hogmanay (pronounced “hog-muh-nay”), the celebration extends well into New Year’s Day and continues for days. Discover some delightful details about this iconic event.

The prominence of Hogmanay in Scotland stems from a nearly 400-year ban on Christmas celebrations.

Before 1560, Christmas in Scotland was a deeply rooted tradition. However, the Reformation brought Presbyterianism, which rejected Catholicism—and consequently, Christmas. By 1640, an act of Parliament had formally prohibited the observance of the December 25 holiday.

The narrative is much the same in England. However, while those in the south eventually revived the holiday—eventually adopting traditions like decorating Christmas trees and sending quirky cards—the Church of Scotland remained steadfast in its opposition to Christmas. Although the ban was formally lifted in 1712, it wasn’t until 1958 that Christmas Day became an official public holiday and gained widespread celebration. During the nearly four centuries without Christmas, Hogmanay emerged as Scotland’s primary winter festival.

In Scotland, the New Year is celebrated with not one, but two public holidays.

While England, Wales, and Northern Ireland observe January 1 as a public holiday, Scotland enjoys both January 1 and 2. While jokes about Scots needing two days to recover from Hogmanay festivities are common, there’s more than a grain of truth to them. January 2 was traditionally a day of rest after the celebrations, and when public holidays were standardized by the Banking and Financial Dealings Act 1971, January 2 was officially recognized in Scotland to honor this tradition.

The first individual to cross the threshold of a home on January 1 is referred to as the “first footer.”

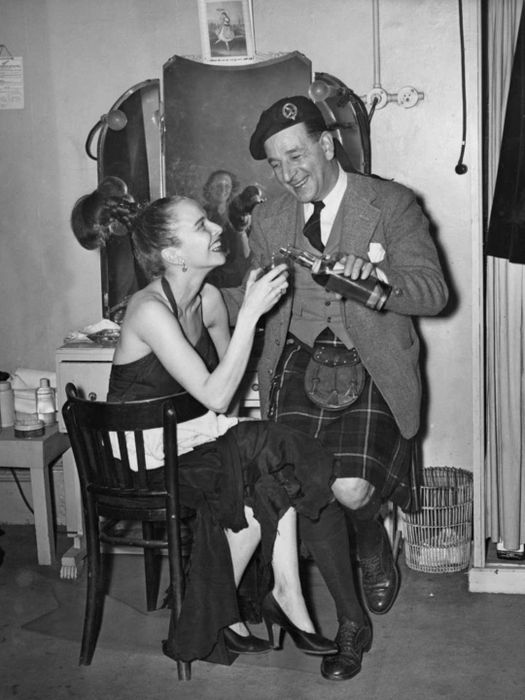

British comedian Ronald Shiner (1903–1966) performs the Scottish Hogmanay ritual of first-footing alongside actress Joan Tetzel (1921–1977). | Reg Speller/GettyImages

British comedian Ronald Shiner (1903–1966) performs the Scottish Hogmanay ritual of first-footing alongside actress Joan Tetzel (1921–1977). | Reg Speller/GettyImagesToday, first footing is less widespread than in the past, but those who continue the custom visit homes after midnight, bringing symbolic gifts like coins for wealth, coal for warmth, and whisky for a celebratory sip. A superstition holds that the first footer should be a dark-haired man for good fortune, a belief possibly linked to the Viking era, when fair-haired strangers often signaled danger.

The origin of the term Hogmanay remains a mystery.

While the exact origin of the Scots word for New Year’s Eve is unknown, several theories exist. Dr. Donna Heddle, director of the Centre for Nordic Studies at Orkney and Shetland College UHI, suggests that “the most plausible origin is French. In Normandy, gifts exchanged at Hogmanay were called hoguignetes.” This theory is bolstered by the spread of Hogmanay in Scotland after Mary, Queen of Scots returned from France in 1561. Heddle also notes possible connections to the Anglo-Saxon phrase haleg monath, meaning “holy month;” the Scandinavian term hoggo-nott, referring to “yule;” or the French word hoginane, meaning “gala day.”

The Scottish tradition of singing “Auld Lang Syne” to ring in the New Year has become a worldwide phenomenon.

“Auld Lang Syne,” meaning “for old time’s sake,” is commonly credited to Scottish poet Robert Burns, though its origins are a bit more nuanced. Burns himself noted, “I learned it from an old man.” Historians agree that he likely added his own touch when he transcribed the lyrics in 1788. The famous tune was composed by music publisher George Thompson in 1799, and it quickly became a Hogmanay staple. The song gained global fame after bandleader Guy Lombardo and his orchestra performed it during a 1929 New Year’s Eve radio broadcast.

Edinburgh’s Hogmanay Street Party ranks among the largest New Year’s Eve celebrations globally.

Edinburgh’s Hogmanay is not only Scotland’s largest New Year’s Eve event but also one of the most significant in the world. Since 1993, the official street party has taken place on Princes Street beneath Edinburgh Castle, featuring live performances and a spectacular midnight fireworks show launched from the castle walls.

The December 31, 1996, street party reportedly attracted approximately 300,000 attendees, prompting safety concerns. As a result, the following year’s event introduced ticketing and capped attendance at 180,000.

The town of Stonehaven marks the occasion with a unique fireball ritual.

Stonehaven’s Hogmanay revolves around a fireball ceremony, where a group of about 40 individuals parades down the main street, swinging large flaming orbs above their heads. These fireballs consist of wire mesh filled with combustible materials such as cardboard and newspaper. Spectators gather along the street hours before midnight, and as the clock strikes 12, a pipe band guides the procession to the harbor, where the fireballs are tossed into the sea—only to be retrieved later for reuse the following year.

In Scotland, it’s customary to enjoy steak pie on New Year’s Day.

The exact reason behind the tradition of eating steak pie on January 1 remains unclear. A popular theory suggests that, before the day became a holiday, families were too occupied with work to prepare meals, so they would purchase a steak pie from the butcher instead.

The Loony Dook involves taking a chilly plunge into the sea on New Year’s Day.

The Loony Dook—loony meaning “lunatic” and dook being the Scots term for “dip”—entails diving into the frigid waters of the Firth of Forth, near Edinburgh, often in humorous costumes. The tradition began in 1987 when Jim Kilcullen, while at a bar with a friend, proposed, “Let’s jump into the Forth on New Year’s Day—it might cure our hangovers!” His friend Andy Kerr coined the name Loony Dook, and what started as a quirky idea between friends evolved into an annual event, with around 1000 participants braving the icy waters each year.

While the Loony Dook has not been part of Edinburgh Hogmanay’s official program in recent years—owing to Covid-related restrictions and funding issues—enthusiasts can still join in unofficially. Additionally, unofficial New Year’s Day dips occur in various icy locations throughout Scotland.