In August of 1815, Napoleon departed for Elba, where the fallen emperor was granted the title of ruler, overseeing an island community of 12,000 people. Not all exiles enjoyed such power, but for some of the world's greatest minds, being exiled—or choosing to exile themselves—became the catalyst for some of their most renowned works.

1. Ernest Hemingway—The Sun Also Rises

University of South Carolina

Sent to France as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, Hemingway embraced the expatriate lifestyle so much that he made it his own. He lived in Paris in voluntary exile, crafting his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises during this time. It's easy to imagine how some parts of the book might have been influenced by his own experiences, with dialogues such as:

Listen, Robert, moving to a new country doesn’t solve anything. I’ve tried that. You can’t escape yourself by relocating. There’s no magic in that.

2. Albert Einstein—Manhattan Project letter

Wikimedia Commons

A well-known pacifist—having once stated “I loathe all armies and any kind of violence”—Einstein fled Nazi-controlled Germany in 1933, seeking refuge in the United States. Six years later, along with Hungarian immigrant Leo Szilard, Einstein wrote a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt warning about the imminent threat of German scientists building an atomic bomb and urging the U.S. government to begin its own uranium research.

That letter, coupled with meetings between Einstein and Roosevelt, sparked the series of events that led to the Manhattan Project in 1942, making the United States the only nation in World War II to successfully develop an atomic bomb. Just five months before his death in 1954, Einstein revisited his decisions, stating, “I made one great mistake in my life... when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification—the danger that the Germans would make them.”

3. Oscar Wilde—The Importance of Being Earnest

NYU

The Irish playwright, initially imprisoned in England on charges of sodomy and gross indecency under his own name, Oscar Wilde, left Britain in 1897, taking the name of Sebastian Melmoth in exile. Ill and destitute, Wilde borrowed the surname from a character in his great-uncle Charles Maturin's gothic novel Melmoth the Wanderer.

In Paris, Wilde released The Importance of Being Earnest, yet he chose not to take credit for it on the playbill—the first edition's cover credited it as “by the author of Lady Windermere’s Fan.” Despite his affection for the play, Wilde admitted to losing his passion for writing after completing it: “The first act is ingenious; the second, beautiful; the third, abominably clever,” Wilde remarked.

4. The Rolling Stones—Exile on Main Street

Amazon

The Rolling Stones may have been exiled on Main Street, but their departure from England in 1971 was due to tax troubles. “After eight years of work, I found out nobody had paid my taxes, and I owed a fortune. So, I had no choice but to leave,” admitted the ever-defiant frontman Mick Jagger. “I just said f*** it, and left the country.”

Before the British authorities could seize their property, the band settled in France. When it came time to record Exile on Main Street, Keith Richards converted his basement in Villefranche-sur-Mer into an impromptu studio, using the band's mobile recording truck. In 1972, the same year their anthem of exile was released, the Stones began using banks in Holland, where royalties were not taxed under Dutch law.

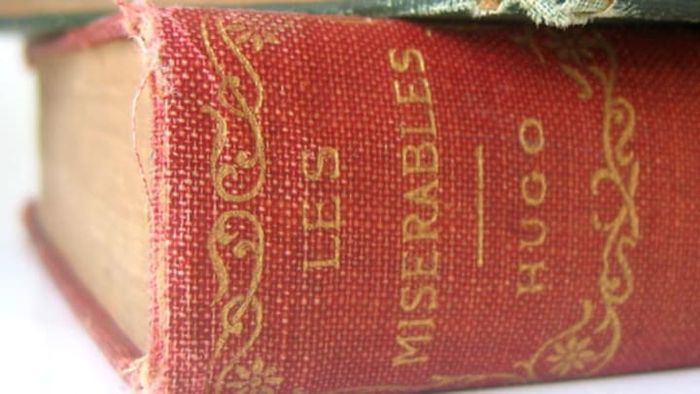

5. Victor Hugo—Les Miserables

Flickr: rfranklinaz

Initially expelled from France due to his fierce opposition to Napoleon III's empire, Hugo was later exiled from both Belgium and the island of Jersey. From a place 26 miles away from his homeland, Hugo penned, “Exile has not only torn me from France, it has nearly severed me from the Earth itself.” Yet, in October 1855, Hugo found his “haven of hospitality and freedom” in Guernsey, a neighboring island to Jersey in the English Channel.

It was in Guernsey that Hugo resumed work on his previously abandoned novel, Les Miserables, along with other works like Toilers of the Sea and volumes of poetry, including Les Contemplations. Driven by the awareness of his own mortality, Hugo wrote relentlessly, as he feared that his “current refuge” might soon become his “likely tomb,” given that he was in his 50s when he arrived in Guernsey.

6. Dante—The Divine Comedy

Wikimedia Commons

As one of six politicians ruling Florence, Dante exiled many of his political rivals before facing exile himself in January 1302 for siding with the Holy Roman Emperor rather than the papacy. Should he return to Florence without paying a hefty fine, the punishment would be burning at the stake.

During his 20 years of wandering across Italy, Dante wrote his monumental three-part epic poem The Divine Comedy, even dedicating the final canto of the work (“Paradiso”) to the struggles of exiles. Dante never returned to Florence, even after the penalty was reduced to house arrest, but the city only cleared his criminal record in 2008—about 700 years too late.

7. Pablo Neruda—Canto General

O Grifo e Meu

Praised as “one of the greats…A Whitman of the South” by the New York Times, Neruda fled Chile for Mexico in self-imposed exile, as his pro-Marxist views earned him few allies. During his three years in Mexico, Neruda wrote Canto General, an extensive poetry collection that aimed to capture the history of Hispanic America across 15,000 lines.

Neruda returned to Chile and, in 1971, became a Nobel laureate. Two years later, he nearly faced a second exile—during the Chilean coup d’état of 1973, when a military dictatorship took over the country. Both Mexico and Sweden offered to shelter Neruda and his wife. When Chilean armed forces raided his home, Neruda humorously responded, “Look around—there's only one thing of danger for you here—poetry.”

8. Frédéric Chopin—Funeral March

The third movement of Chopin’s Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Major takes inspiration from the often-mocked Rossini opera La Gazza Ladra—a bold choice, given that the movement is a mournful funeral march. Composed in the 1830s, while Chopin was an expatriate in Paris and part of Poland’s Great Emigration, the piece became iconic. Although he rarely performed publicly in France, according to NPR, “His colleagues said that he often played in salons, and the only way to get him to stop playing was to get him to play the March.”

The somber melody may also ring a bell for sci-fi enthusiasts. “The Imperial March,” the famous John Williams composition that signals Darth Vader’s arrival in Star Wars, was inspired by Chopin’s unforgettable tune.

9. Sigmund Freud—An Outline of Psycho-Analysis

Barnes and Noble

Despite being 82 when he arrived in London in 1938, escaping the Nazi regime in Germany, Freud settled into his home at 20 Maresfield Gardens. There, the elderly psychoanalyst worked on a final summary of his life's work entitled An Outline of Psycho-Analysis, which he had begun writing while still in Vienna before his move to London.

By September of 1938 (having arrived in June), Freud had completed three-fourths of the manuscript. However, due to his ongoing battle with cancer and a final surgery in 1938, the book remained unfinished. A year after Freud’s death in 1939, the incomplete three-part work was released posthumously.