The 14-foot tiger shark at Sydney's Coogee Aquarium was acting unusually. It had lost the vigor and hunger it displayed upon its arrival a week earlier, on April 17, 1935. Moving lethargically in its 25-by-15-foot enclosure, it collided with the walls and sank to the bottom, as though burdened by something heavy.

Suddenly, the shark convulsed violently and expelled the contents of its stomach. As the water cleared, onlookers were horrified to see a partially digested human arm floating in the pool.

In 1935, Australians were quick to blame sharks for fatalities. A series of shark attacks had already terrified the southeastern coast that year, cementing the creatures' reputation as predators. When the aquarium's shark regurgitated the severed arm, many believed it was proof of yet another fatal shark attack.

The situation grew even more disturbing—and peculiar—as additional facts came to light. According to the coroner’s findings, the arm had not been torn off by a shark but had been neatly severed with a blade. This indicated that the shark was not involved in the apparent homicide. Though the shark couldn’t provide testimony, investigators didn’t need its account to proceed; the fingerprints and a distinctive boxing tattoo on the arm offered crucial clues to unraveling one of Australia’s strangest murder cases.

Something Suspicious

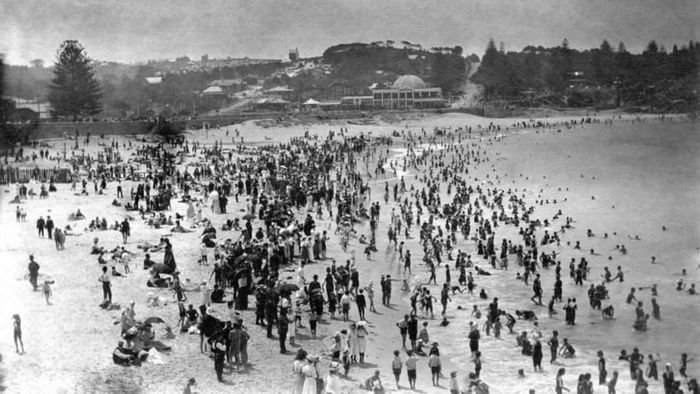

Coogee Beach circa 1905. The Coogee Aquarium is visible in the background. | Robert Augustus Henry L'Estrange, Wikimedia Commons // CC0

Coogee Beach circa 1905. The Coogee Aquarium is visible in the background. | Robert Augustus Henry L'Estrange, Wikimedia Commons // CC0After the summer of 1935, Sydney locals may have feared encountering sharks at the beach, but they were fascinated by the idea of seeing one in captivity. Bert Hobson, owner of the Coogee Aquarium, recognized this curiosity while fishing with his son Ron near Coogee Beach in mid-April. While reeling in a smaller shark, they accidentally hooked a massive 14-foot, 1-ton tiger shark. After hauling it ashore, Hobson decided to showcase the colossal creature as the main attraction at his aquarium.

The new attraction proved to be a game-changer for the Coogee Aquarium. After the nearby Coogee Pier—home to a penny arcade and a 1400-seat theater—was demolished, visitor numbers had dwindled. However, the arrival of a terrifying tiger shark drew crowds, giving the aquarium a much-needed boost in popularity.

The excitement surrounding the shark reached its height on Anzac Day. Comparable to Memorial Day in the U.S., this holiday is celebrated in Australia and New Zealand on April 25. Many took advantage of the day off to visit the Coogee Aquarium, heading straight for the tiger shark exhibit. After a summer filled with shark attack headlines, seeing one up close in a controlled setting offered a strange sense of relief. The shark symbolized humanity's control over the ocean—until it unexpectedly regurgitated a piece of human remains.

Narcisse Leo Young, a proofreader for The Sydney Herald, was among the visitors that day. "I stood just a few meters away and watched as the shark expelled a thick, foul-smelling brown foam," he recalled. Along with the arm, the shark also vomited a bird, a rat, and a heap of debris.

The coroner’s report debunked the idea that the shark was a maneater, but the real danger lay elsewhere—a killer was still at large. To catch the culprit, authorities first needed to determine the identity of the victim.

Lost and Found

Edwin Smith was engrossed in the news about the Coogee Aquarium incident when a specific detail caught his attention: the description of a unique tattoo on the arm found in the tiger shark’s pool. The tattoo, located on the forearm, featured two boxers in a fighting stance, ready to clash.

Smith instantly recalled his brother James, who bore an identical tattoo in the same spot—and who had been missing for weeks.

Though shocking, the revelation that Jim Smith had been murdered and partially consumed by a shark wasn’t entirely surprising. The 45-year-old, originally from England and living in Gladesville, Australia, managed a billiards hall and had a checkered past as both a criminal and a police informant. After his boxing career faltered, he took on various jobs in Sydney, including managing the billiards saloon and working for Reginald Holmes, a boat-building tycoon with ties to organized crime.

Holmes used his legitimate boat business as a cover for illegal activities. His speedboats were instrumental in smuggling drugs from ships in Sydney Harbor into the city. He also orchestrated forgery and insurance fraud schemes, with Smith and an ex-convict named Patrick Brady playing key roles.

One of Holmes’s most notorious scams involved an over-insured yacht. He enlisted Smith to secretly sink the Pathfinder, after which Holmes filed an insurance claim. However, Smith tipped off the police, labeling the incident as suspicious, leaving Holmes to bear the financial loss. This betrayal caused a rift between the two, which deepened when Smith allegedly began extorting Holmes.

Smith was last spotted drinking and playing cards with Patrick Brady at the Cecil Hotel in Cronulla on the evening of April 7. As the night wore on, they moved to a cottage Brady rented on Tallombi Street. Later, Brady, appearing disheveled, took a cab from the cottage to Holmes’s residence—without Smith.

The tattooed arm recovered from the shark provided crucial clues about Jim Smith’s disappearance. Edwin alerted the police, linking the tattoo to his missing brother. Using a cutting-edge forensic method, investigators matched the fingerprints on the severed hand to Smith, confirming his identity. It was clear Smith had met a violent end, and the authorities quickly zeroed in on their main suspects.

Untangling the Tale

Despite having two suspects, a motive, and a severed arm, the case remained unresolved. Police lacked the concrete evidence needed to make arrests. Instead, they detained Brady on unrelated forgery charges. After six hours of intense questioning, Brady finally admitted what investigators had suspected: Reginald Holmes was the mastermind behind the crime.

Holmes seemed to sense the police were closing in. By the time authorities reached his home, he was speeding across Sydney Harbor in a boat, clutching a bottle of liquor. At one point, he halted the vessel, stood before a crowd of onlookers, and delivered a cryptic warning: “Jimmy Smith is dead, and there’s only one more left […] If you leave me until tonight, I’ll finish him.” He then shot himself in the head and fell into the water.

For a brief moment, it seemed the investigation had hit a wall—but against all odds, Holmes survived.

The bullet only grazed his forehead, leaving a non-lethal wound, and he managed to climb back onto his boat. After a tense pursuit, authorities apprehended Holmes, but extracting a confession was no easy task. He pointed the finger at Brady, accusing him of Smith’s murder and claiming he himself was a victim of blackmail. Holmes insisted Brady had acted alone, killing and dismembering Smith at the Tallombi Street cottage. According to Holmes, Brady disposed of most of the body in the ocean but kept the arm to intimidate him. Holmes alleged that Brady brought the arm to his house, threatening him unless he paid up. In a panic, Holmes claimed he threw the arm into the water, where the tiger shark eventually consumed it.

Regardless of the story’s accuracy, investigators deduced that the arm was likely eaten after being discarded in the ocean. The timeline aligned: tiger sharks digest slowly, and the arm could have remained in the shark’s stomach for up to 18 days before being regurgitated. It’s even possible the arm was inside the smaller shark Bert Hobson initially caught, which was then eaten by the tiger shark—creating a bizarre, unappetizing chain of events. However, how the arm ended up in the water in the first place remains a mystery.

The Case Goes Cold

ricardoreitmeyer/iStock via Getty Images

ricardoreitmeyer/iStock via Getty ImagesOn the morning of the inquest, which Holmes was scheduled to attend, police discovered him in his car with three gunshot wounds to his chest. It’s believed he hired assassins to carry out the deed after securing a large life insurance policy. Since the policy would be invalidated by suicide, Holmes used his cunning to orchestrate one final scheme for his family’s benefit.

Patrick Brady lived to face trial for murder, but the case wasn’t as straightforward as prosecutors had anticipated. Without Holmes’s testimony, the evidence was less compelling. The defense argued that a single arm wasn’t sufficient proof of murder, and it was possible Smith was still alive. Brady was acquitted and maintained his innocence until his death in 1965 at the age of 76.

The shark arm case claimed more than just Smith and Holmes. Shortly after regurgitating the arm, the tiger shark from the Coogee Aquarium was euthanized and dissected. The autopsy yielded no additional body parts or answers, rendering the effort futile.

While many details of the 1935 Coogee Aquarium incident have been clarified, the full truth about Jim Smith’s disappearance remains elusive. Even if new evidence surfaces, it’s unlikely to overshadow the dramatic and chaotic origins of this infamous case in the public’s memory.