A team of computing scientists from the University of Alberta has made a daring assertion: they believe they have pinpointed the source language of the cryptic Voynich Manuscript, achieved through the use of artificial intelligence.

Their research, published in Transactions of the Association of Computational Linguistics [

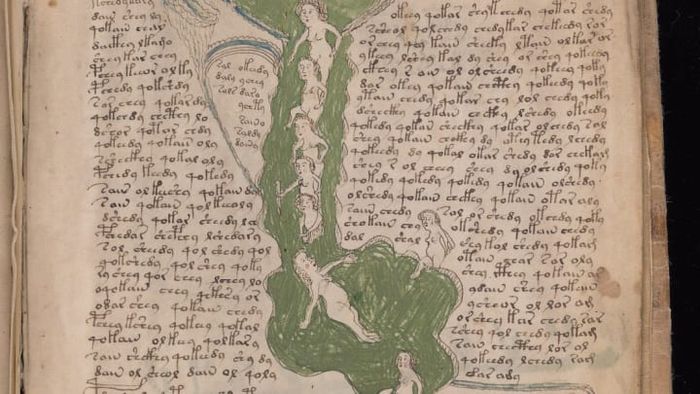

For anyone familiar with the Voynich Manuscript, this skepticism is understandable. The book, which features 246 pages of mysterious illustrations and what appears to be a foreign script, remains shrouded in mystery. It is named after Wilfrid Voynich, the Polish book dealer who acquired it in 1912, but scholars believe it was created over 600 years ago. Little is known about the author or the manuscript’s purpose.

Many cryptographers believe the manuscript is a cipher—an encoded sequence of letters that needs to be deciphered to make sense. Yet, after decades of effort from the world’s top cryptographers testing countless possibilities, no one has been able to crack the code. The researchers at the University of Alberta, however, claim to have taken a different approach. Rather than relying on human linguists and codebreakers, they developed an AI system designed to recognize the source languages of texts. They trained the AI on 380 versions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, each translated into different languages and encrypted. Once the AI learned to identify patterns in various languages, it was given pages from the Voynich Manuscript. Based on its prior training, the AI identified Hebrew as the original language of the manuscript—a surprising finding for the researchers, who had expected Arabic.

The team then created an algorithm to rearrange the scrambled letters into proper words. They managed to translate 80 percent of the encoded words in the manuscript into real Hebrew. Their next step was to consult an expert in ancient Hebrew to evaluate whether the reconstructed words made sense together.

However, the researchers claim they couldn’t reach any scholars, so they turned to Google Translate to interpret the first sentence of the manuscript. The translated words in English read, “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.” Study co-author Greg Kondrak commented, “It’s a rather odd way to begin a manuscript, but it definitely makes sense.”

Elonka Dunin, however, is less optimistic. She argues that identifying a possible cipher and source language without translating more of the manuscript isn’t cause for celebration. “They identified a method without decrypting a full paragraph,” she says. Dunin also questions the AI’s approach, noting that it was trained using ciphers created by the researchers themselves, not real-world ciphers. “They scrambled the texts using their own system, then used their own software to unscramble them. After that, they applied it to the manuscript and concluded, ‘Oh look, it’s Hebrew!’ It’s a big leap,” she adds.

The University of Alberta researchers aren’t the first to claim they’ve identified the language of the Voynich Manuscript, and they certainly won’t be the last. However, unless they manage to decode the entire manuscript into a coherent language, it remains just as mysterious as it was 100 years ago. For those like Dunin, who believe the book might be a constructed language, an elaborate hoax, or even the result of mental illness, the manuscript remains an unsolved enigma without a satisfying answer.