Boy George narrowly escaped a tragic encounter with a disco ball.

During a 1998 rehearsal in Dorset, England, the pop icon was nearly struck by a 62-pound mirrored ball that fell from above. The massive object grazed his face and sent him tumbling to the ground after a wire gave way. Onlookers reported it missed his head by a mere two inches.

This close call was just one of many misfortunes—not for the “Karma Chameleon” artist, but for the disco ball itself, a hallmark of 1970s nightlife alongside flared trousers and cocaine. Suspended above partygoers, it spun endlessly, casting shimmering lights and serving as a beacon for those seeking escape and euphoria on the dance floor.

However, the disco ball’s origins predate the disco era. To uncover its history, one must travel further back in time and credit its true creators: electricians.

Mirror, Mirror

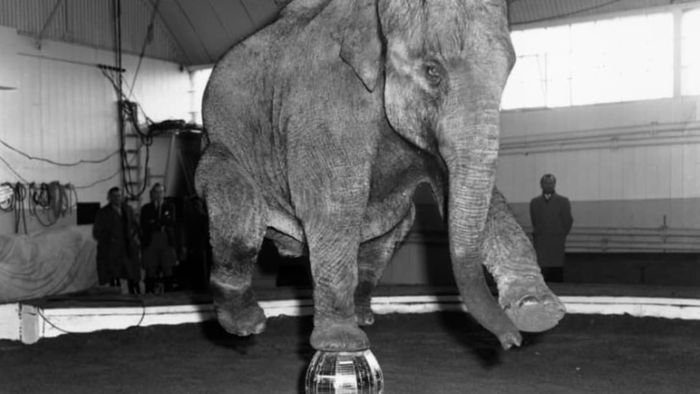

Laxmi the elephant rehearses a trick standing atop a mirror ball in 1959. | Ron Case/Keystone/Getty Images

Laxmi the elephant rehearses a trick standing atop a mirror ball in 1959. | Ron Case/Keystone/Getty ImagesAs reported by Vice, the earliest documented reference to a mirrored ball appeared in an 1897 edition of The Electrical Worker, a trade magazine for union members in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The publication detailed the union’s annual gathering and its decorations, including a carbon arc lamp designed to reflect light off a “mirrored ball.”

The mirrored ball was likely a unique creation crafted specifically for the event, as it wasn’t until 1917 that Louis Bernard Woeste patented his “myriad reflector.” His Cincinnati firm, Stephens and Woeste, began selling these spheres in the 1920s, marketing them as a way to transform dance halls into spaces filled with “dancing fireflies of a thousand hues.”

These early versions measured 27 inches across and featured over 1200 small mirrors, casting a dazzling array of colors. At the time, dance halls lacked modern effects like strobe lights or fog machines, maintaining a more subdued ambiance. The myriad reflector fit seamlessly into these venues, appearing at dances, jazz clubs, skating rinks, and even circuses, where animals sometimes performed atop reinforced versions. (The name also evolved, with people preferring terms like mirror ball or glitter ball over Woeste’s more formal label.)

While the globes enjoyed moderate success, they never became a sensation, leading Stephens and Woeste to eventually phase them out. Production was later taken over in the 1940s and 1950s by Omega National Products of Louisville, Kentucky, a company known for creating flexible mirrored sheets for Art Deco furniture. Some customers sought mirrored accents for items like Kleenex boxes, while others, such as Liberace, desired grander applications, like covering entire pianos in reflective material.

Mirrored balls were a logical next step, and Omega produced them on demand for dance venues. However, their rise to pop culture prominence didn’t occur until the 1970s.

Saturday Night Fever

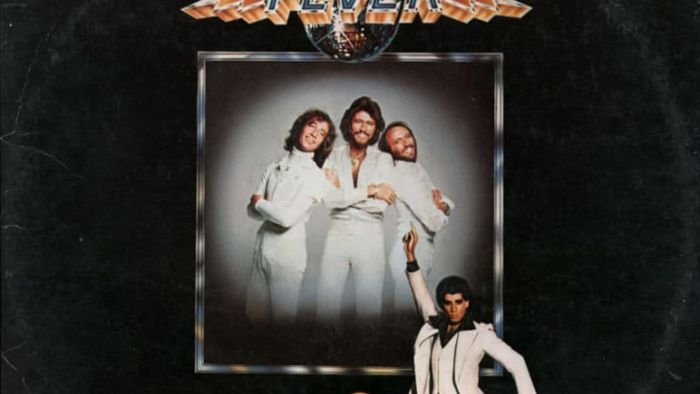

Saturday Night Fever made a star of disco--and disco balls. | Blank Archives/Getty Images

Saturday Night Fever made a star of disco--and disco balls. | Blank Archives/Getty ImagesThe rise of disco in the 1970s revolutionized nightlife. Across the nation, young people were captivated by the genre’s infectious beats and sensory-rich experience. Clubs transformed into vibrant spaces with dazzling lights, making patrons feel as though they were inside a pinball machine. The disco ball, suspended above the crowd, became the ultimate symbol of this new form of escapism.

Omega seized the opportunity to dominate the market. At the peak of disco’s popularity in the mid-1970s, 90 percent of America's supply of disco balls came from Omega. Their team of 25 workers meticulously crafted 25 balls daily by hand, attaching reflective sheets to metal spheres. A 48-inch model could fetch $4000, equivalent to around $20,000 today, but clubs eagerly invested, recognizing the disco ball as an essential element of their ambiance.

The disco ball even earned a quasi-starring role in Saturday Night Fever, the 1977 blockbuster featuring John Travolta as Tony Manero, a restless New Yorker who finds solace and excitement in the city’s disco culture.

The film propelled disco to unprecedented heights, with roughly 20,000 disco clubs springing up nationwide. In Bloomington, Indiana, a couple even exchanged vows beneath a disco ball as the Bee Gees’ “How Deep Is Your Love?” played in the background. Meanwhile, in Fort Worth, Texas, a company called Disco Delite provided mobile disco setups, complete with a ball and sound systems, to transform any dull space into a lively party. However, the fascination with disco’s iconic imagery wasn’t destined to endure.

Fading Out

The disco backlash of the late 1970s kept the disco ball from spinning. | Blank Archives/Getty Images

The disco backlash of the late 1970s kept the disco ball from spinning. | Blank Archives/Getty ImagesDisco’s decline was partly due to fading trends but was accelerated by widespread opposition. In 1979, a promotional event at Chicago’s Comiskey Park during a baseball game spiraled out of control when attendees were encouraged to bring disco records to destroy. Disco Demolition Night became a disaster, forcing the Chicago White Sox to forfeit as the crowd and bonfires grew uncontrollable. (The event also revealed underlying racism, as large quantities of R&B records were burned alongside disco albums.)

Whether influenced by such resistance or not, disco’s era in the limelight had largely concluded; the once-captivating ceiling-hung ball became a relic of a bygone trend. By the time John Travolta starred in the 1983 sequel Staying Alive, following Saturday Night Fever, disco balls were nowhere to be seen.

The disco ball hasn’t faded entirely into obscurity. In 2016, Louisville—dubbed the unofficial disco ball capital of the world—honored Omega by constructing an 11-foot, 2300-pound ball at a cost of $50,000. Omega continues to produce these spheres, though now only one worker is needed to fulfill orders, compared to the 25 required in the past.

You might still encounter a disco ball in unexpected places, such as concerts for nostalgic appeal or even in repurposed buildings. For years, a Manhattan Rite Aid baffled customers with a disco ball mounted on its ceiling—a remnant of its former life as a roller rink.

As for Boy George: After being treated for a bruised ear in 1999, he returned to the stage that same night to perform. “I have survived and I’m still here,” he declared, a statement that could equally apply to the enduring disco ball.