The longstanding enigma surrounding Hippocrates and the parasitic worms has been unraveled, thanks to a few samples of ancient stool.

While much remains unknown about the parasites that afflicted the ancient Greeks, much of the knowledge we do have stems from the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of medical writings compiled by Hippocrates and his students between the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. For years, modern historians have been piecing together clues from these texts to identify the diseases and parasites the Greeks faced, relying on descriptions to make educated guesses. Now, however, they have definitive evidence of some of the intestinal worms Hippocrates mentioned, namely Helmins strongyle and Ascaris.

In a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, an international team of researchers examined ancient feces found in 25 prehistoric burials on the Greek island of Kea. Their goal was to identify the parasites carried by individuals at the time of their death. Using microscopes, the team analyzed the soil (formed from decomposed stool) found on pelvic bones from skeletons dating back to the Neolithic, Bronze, and Roman periods.

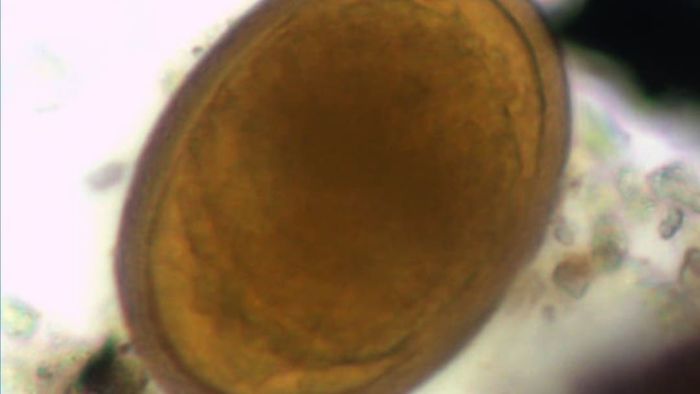

An egg of a roundworm | Elsevier

An egg of a roundworm | ElsevierApproximately 16 percent of the burials they examined revealed signs of parasites. In the ancient fecal samples, they discovered eggs from two distinct parasitic species. In the soil from Neolithic skeletons, they identified whipworm eggs, while the soil from Bronze Age remains contained roundworm eggs.

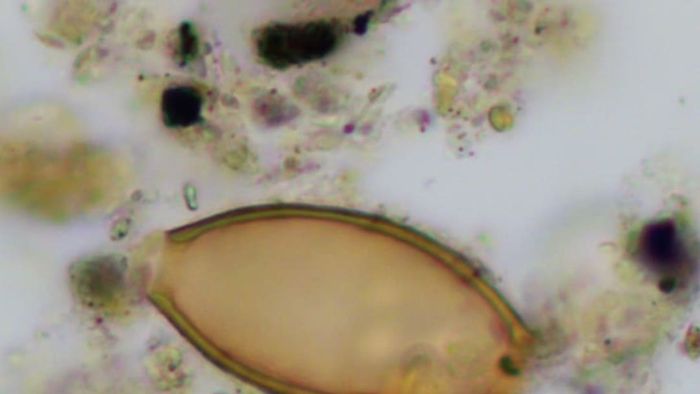

From this data, the researchers concluded that the Helmins strongyle mentioned by Hippocrates was likely what modern medicine refers to as roundworm. They further speculated that the Ascaris worm described by Hippocrates likely referred to two different parasites, which are known today as pinworm (not found in this study) and whipworm (shown below).

A whipworm egg | Elsevier

A whipworm egg | ElsevierAlthough historians had previously speculated that Hippocrates's patients on Kea suffered from roundworm, the discovery of Ascaris is a surprising twist. Earlier research, relying only on Hippocrates's writings rather than physical evidence, suggested that what he described as Ascaris was likely pinworm, and another worm he referenced, Helmins plateia, was probably a tapeworm. However, the latest study found no traces of either of these parasites. Instead of pinworm eggs, the researchers discovered whipworm, another small, round parasite. (The researchers note that pinworms may have existed in ancient Greece, but their delicate eggs may not have survived.) This soil analysis has already shifted our understanding of the intestinal health issues faced by the ancient Greeks on Kea.

More importantly, this research provides the earliest evidence of ancient Greece’s parasitic worm population, reinforcing once again that ancient poop is an invaluable scientific resource.