A Dimetrodon skeleton showcased at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, highlights its iconic sail structure. Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty Images

A Dimetrodon skeleton showcased at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, highlights its iconic sail structure. Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty ImagesThe remains of Dimetrodon, an ancient predator that roamed North America and Europe approximately 295 to 275 million years ago, are instantly recognizable due to the striking sail adorning its back.

That large, fan-like bony feature? It’s impossible to overlook.

However, don’t overlook the other features of this creature. The teeth and skull openings of Dimetrodon have allowed paleontologists to identify it as part of the same animal group that eventually led to mammals, including humans.

Belonging to the Synapsid Family

"Dimetrodon is classified as a 'synapsid,'" clarifies Caroline Abbott, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago, via email.

"Approximately 310 million years ago, the earliest amniotes (land-dwelling egg-laying vertebrates) diverged into two distinct lineages: synapsids and reptiles. These groups have followed separate evolutionary paths ever since," Abbott notes. "Dimetrodon is among the earliest synapsids."

Today, mammals are the sole surviving members of the synapsid lineage.

The earliest true mammals didn’t appear until between 178 and 208 million years ago, long after Dimetrodon had gone extinct. However, as a synapsid, this ancient creature shared a closer evolutionary connection to humans than to any living reptiles — or even dinosaurs, as we’ll explore further.

How can we confirm that Dimetrodon was a synapsid? Several clues emerged after its discovery in the 1800s, providing fossil hunters with critical insights.

"A defining trait of all animals in the evolutionary line leading to mammals is a sizable opening behind the eye socket on the skull," explains Hans Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in an email.

"This opening grows larger in more advanced species and accommodates the jaw-closing muscles. You can feel these muscles by placing your fingers on your temples and clenching your jaw," he continues.

Additionally, like many mammals, Dimetrodon was a heterodont. This means its teeth were not uniform but varied in shape and function. As Sues notes, Dimetrodon possessed "incisor-like front teeth, a prominent canine, and smaller teeth located behind the canine."

Neural Spines

Now, let’s talk about that distinctive sail ...

Vertebrae, or backbones, are crowned with bony projections known as "neural spines." In four-legged animals, these spines are positioned vertically. In humans, they point backward and can be felt as small bumps under the skin when touching the back of the neck or spine.

The sail of Dimetrodon was formed by exceptionally elongated, rod-shaped neural spines. The tallest spines were located along the middle of its back, between the shoulders and hips, creating a "dumbbell"-shaped sail. In the largest Dimetrodon specimens, which measured over 15 feet (4.6 meters) in length and weighed up to 550 pounds (250 kilograms), the sail’s peak would have risen at least 5 feet (1.5 meters) above the ground.

That’s slightly higher than the height of an average sedan car.

The Sail Sparks Debate

If you’re curious about the purpose of Dimetrodon’s sail, you’re not alone.

"No one truly knows because there are no modern animals with similar 'sails' to compare it to," Sues clarifies.

Most mammals today maintain a stable internal body temperature. It’s likely that Dimetrodon didn’t have this capability and depended on its surroundings to regulate its temperature — whether to warm up or cool down.

"The tall neural spines, with tissue and blood vessels between them, would have offered a large surface area to assist with thermoregulation, or how an animal manages its body temperature," Abbott explains. "The 'sail' of Dimetrodon could have functioned like a massive solar panel, enabling it to become active earlier and remain mobile longer during the day. That’s a significant advantage for a predator!"

However, researchers remain skeptical.

Dimetrodon thrived during the early Permian Period, spanning approximately 298 to 251 million years ago. Its closest relative, Sphenacodon, shared a similar carnivorous build. Both were early Permian predators, but unlike Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon lacked a prominent sail. This raises the question: why would one species require a "solar panel" while the other managed perfectly well without it?

Could the Sail Have Been a Mating Display?

Sexual selection might hold the key. If the sail wasn’t for temperature regulation, it could have served as an ancient attraction mechanism.

Abbott points out that "ornamental features often evolve due to mate preferences, like vibrant bird plumage or deer antlers. In this context, a 'sail' for display purposes might have developed because other Dimetrodon found it attractive for selecting mates."

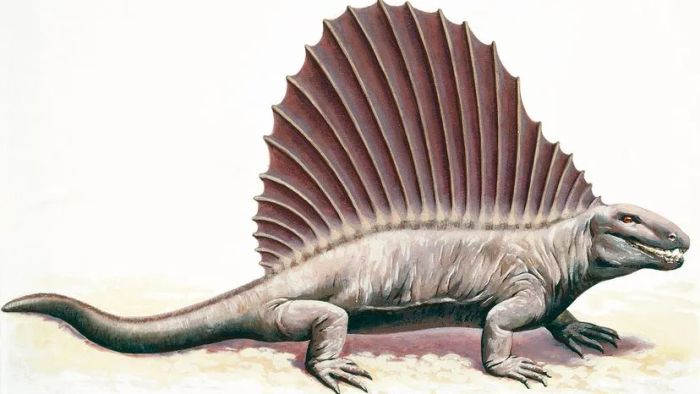

This artwork depicts how the sail of Dimetrodon, a four-legged synapsid from the Permian Period, likely appeared in real life.

DeAgostini/Getty Images

This artwork depicts how the sail of Dimetrodon, a four-legged synapsid from the Permian Period, likely appeared in real life.

DeAgostini/Getty ImagesRegardless of the sail’s true function, one thing is certain: it wasn’t exclusive to Dimetrodon. The herbivorous Edaphosaurus, another synapsid from Permian-era fossils, also sported a prominent sail. Similarly, the ancient amphibian Platyhystrix had one. Long after these creatures vanished, certain dinosaurs independently developed similar features.

Was Dimetrodon a Dinosaur?

The most renowned sail-backed dinosaur is undoubtedly Spinosaurus. It existed during the Cretaceous Period around 97 million years ago. Measuring an estimated length of nearly 50 feet (15 meters), it may have been the largest land-dwelling carnivore ever, though it likely favored hunting in aquatic environments.

This brings us to one of the scientific community’s biggest frustrations regarding Dimetrodon. As a precursor to mammals, Dimetrodon had no connection to creatures like T. rex, Triceratops, or Spinosaurus. Yet, it is often incorrectly identified as a dinosaur.

Toy manufacturers share some responsibility. Dimetrodon is frequently misclassified as a "dinosaur" in playsets and collections of plastic models. Hollywood perpetuates this error; films like "Fantasia" or "The Land Before Time" depict this Permian synapsid mingling with true dinosaurs.

The unfortunate truth is that Dimetrodon vanished millions of years before dinosaurs even appeared. "We are closer in time to Spinosaurus than Spinosaurus is to Dimetrodon!" Abbott remarks.

Fossil Evidence Reveals Only Surface Details

Unlike the two-legged Spinosaurus, Dimetrodon moved on all fours, as fossil evidence confirms. However, many details about its appearance and behavior remain shrouded in mystery.

"While no skin impressions have been found with Dimetrodon fossils, it’s probable the creature had scales and no hair. This assumption is based on our limited understanding of when hair evolved in synapsids and indirect evidence from trackways," Abbott explains.

In 2012, researchers documented fossilized footprints and belly impressions from an early Permian synapsid, believed to be similar to Dimetrodon. The tracks revealed the presence of distinct belly scales.

Regarding synapsid hair, evidence confirms it evolved by 164 million years ago, as the earliest definitive mammal hair imprints appear in the fossil record. "Possible hair-like structures have been identified in Late Permian coprolites (fossilized feces), dating 10 to 20 million years after the last Dimetrodon," Abbott adds.

Budding paleoartists should take these details into account.

Dimetrodon varied greatly in size. "There are 14 recognized species of Dimetrodon—one initially classified under its own genus, Barygnathus," Sues notes. Some species measured just 5 feet (1.5 meters) long from head to tail, while others, as previously mentioned, could reach lengths three times that size.