The dirty, rat-infested shed was far from a fitting place for royalty.

It was November 1853 when Queen Victoria momentarily set aside her royal duties to venture through a mud-soaked plot in south London toward a humble wooden shed. The structure appeared unsuitable for housing animals, let alone workers and esteemed visitors, yet inside, a scene of activity stirred the queen’s great delight.

Dinosaurs were being resurrected before her eyes.

The four colossal creatures, each in various stages of completion, towered at 9 feet tall and stretched 32 feet long. Two Iguanodon accompanied Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus, forming the trio of prehistoric species that had only recently been identified and categorized as Dinosauria. These awe-inspiring figures were set to be the centerpiece of Crystal Palace Park, a partially glass-enclosed exhibition space designed to dazzle Londoners with an array of remarkable sights. No one had ever seen dinosaur sculptures to this scale before. Given Queen Victoria’s prior visits, she and Prince Albert would be among the first to witness them upon completion.

The visionary behind this groundbreaking achievement in what would later be known as paleoart was Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, a sculptor who dedicated years to creating what he saw as four dinosaur-sized dwellings. Despite the scarcity of fossil evidence or reference material, Hawkins managed to breathe life into these ancient creatures in a way that was beyond the reach of flat, two-dimensional depictions. He would later gain acclaim within London’s social circles, travel to the U.S. to recreate his success, and deliver lectures on his remarkable accomplishment.

However, Hawkins would also face criticism for scientific inaccuracies, endure the anger of jilted lovers, and witness his work destroyed by corrupt political forces. Despite helping to ignite the modern fascination with dinosaurs, his name has not remained a household one. In reality, Hawkins was the Steven Spielberg of his era—an artist and visionary who constructed an immersive world where ancient giants once roamed the Earth.

The Bone Hunters

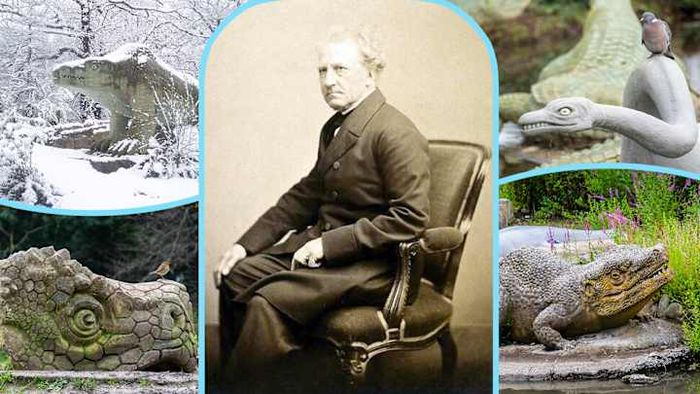

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's 1850 illustration of "The Goat." | Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's 1850 illustration of "The Goat." | Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty ImagesBenjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was born in London on February 8, 1807. On that day, and for the next 35 years, knowledge about prehistoric life was scarce. Although Robert Plot documented what is now believed to be the first discovered dinosaur fossil in 1677, he mistook it for a giant human. The term dinosaur hadn't even been coined yet.

That began to change in the early 1840s when scientist Richard Owen found himself at 15 Aldersgate Street in London and came across a strange fossil from geologist William Devonshire Saull’s collection. Upon examination, Owen identified it as part of the spine of Iguanodon, a species first recognized (by its teeth) in 1821 by Gideon and Mary Ann Mantel. It shared anatomical features, such as fused spines, with other prehistoric creatures, including Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus. These were not merely large reptiles, but something entirely new. Owen would go on to coin the term Dinosauria. (Dinosaur is derived from the Greek for “terrible lizard,” although Owen likely meant “terrible” in a “fearsome” sense.)

While Owen was circulating his theory in the scientific community, Hawkins—who had studied art and sculpture at St. Aloysius College in London—focused on contemporary animals. His fascination with natural history and geology made him a perfect fit for nature illustration. In the 1840s, under the mentorship of Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby, Hawkins sketched living animals at Knowsley Park, even racing to capture the first movements of a newborn giraffe.

Hawkins gained memberships with the Society of Arts, the Linnaean Society, and later the Geological Society of London. However, it was his work in books—illustrating the thrilling expeditions of teams returning with tales of incredible discoveries—that solidified his reputation.

Among those who enlisted Hawkins’s talents was Charles Darwin, who utilized Hawkins for his multi-volume work The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, published between 1838 and 1843. "Darwin came back from his voyage on the Beagle and published several volumes about the trip," says Robert Peck, curator of art and artifacts at the Academy of Natural Sciences at Drexel University and co-author of All in the Bones: A Biography of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. "There were five parts in total, and Hawkins illustrated two of them, the sections on fish and reptiles. He worked directly with Darwin on this. Despite their collaboration, they had completely different views on evolution. Later in life, Hawkins became quite opposed to evolutionary theory."

Hawkins’s rejection of evolution likely stemmed from his association with Owen, with whom he developed a friendship through his illustrations. "Owen was anti-evolutionary and opposed to Darwin’s theories," Peck explains. "Since Hawkins lacked formal scientific training, he relied heavily on Owen’s views. If a respected figure like Owen didn’t accept evolution, Hawkins felt it was not something he should believe in either."

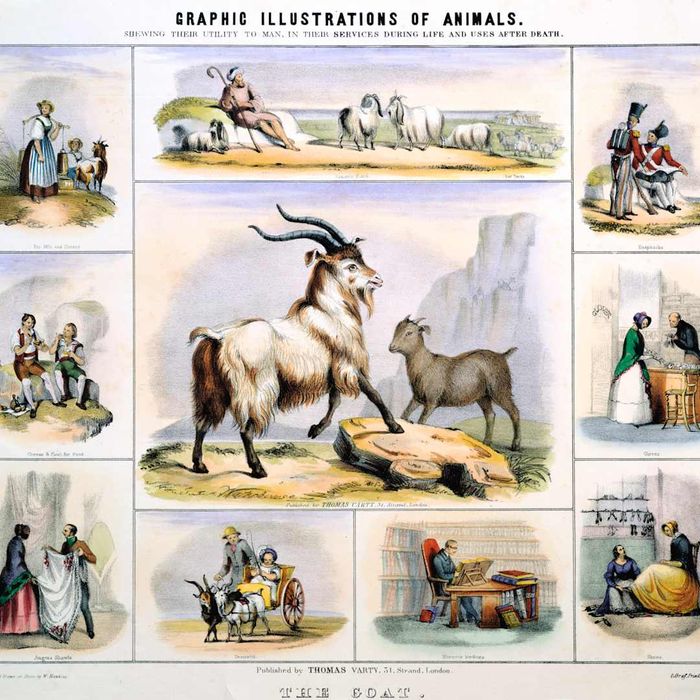

In an era when the field of paleontology had yet to be formally named, Owen was regarded as an authority in the scientific community. As such, it was only natural for both Owen and Hawkins—perhaps with encouragement from the Earl of Derby as well as Owen—to be invited in September 1852 to assist in the relocation of Crystal Palace from Hyde Park to Penge, near Sydenham Hill in south London. (The location is often referred to as being in Sydenham.) The organizers wanted them to create a monumental display of 33 life-sized, extinct animals set within a geologically accurate environment. Originally conceived to host the Great Exhibition of 1851, a precursor to the world’s fair celebrating Victorian arts and sciences, Crystal Palace's new owners sought to revamp the space with fresh attractions for its new location and role as Crystal Palace Park.

An image of Crystal Palace at Sydenham with the park in the foreground, circa 1855. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

An image of Crystal Palace at Sydenham with the park in the foreground, circa 1855. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages“At Sydenham, the goal was to recreate ancient England,” says Peck. “They collected stones, dirt, and gravel, arranging them in a stratigraphic pattern on man-made islands, aiming to depict what England once looked like in three-dimensional form. Then the idea expanded: Why not bring back the creatures that once roamed there but are now extinct?”

Owen was to be the adviser, while Hawkins would assume the roles of designer, architect, artist, and engineer, devising the plan to resurrect Iguanodon and the other extinct creatures.

Although Hawkins wasn’t formally trained in paleontology, he had a solid grasp of animal anatomy—understanding how mammals moved and how reptiles appeared. “All he needed to do was scale it up,” says Peck. “If Owen gave him the approval, Hawkins was ready to follow. Who could question Owen? He was a leading expert in comparative anatomy at that time.”

Hawkins’s background in science made him an ideal choice for the project’s leaders. “They turned to Hawkins because most artists were reluctant to engage with the scientific side,” he says. “If they had approached a sculptor of the era, they might have faced rejection.”

Hawkins began with sketches and small-scale clay models to refine the details. This step was crucial, as many of the artistic decisions were based on assumptions rather than direct fossil evidence. Since no complete dinosaur skeletons had been found at that time, Hawkins studied every available fossil fragment at institutions like the British Museum, the Royal College of Surgeons, and the Geological Society. He also heavily relied on French naturalist Georges Cuvier’s theory that small fragments could help reconstruct the entire organism—that a few body parts could provide clues to the full anatomical structure. It was speculative, driven by the best knowledge of the time. Paleoart, which would evolve in the future, was still in its infancy.

“While there had been impressive two-dimensional paleoart, including paintings, no one had attempted to create life-sized or three-dimensional reconstructions,” explains Mark Witton, a paleontologist and paleoartist from the UK, in an interview with Mytour. “[Hawkins’s] work was essentially about bringing the two-dimensional depictions of prehistoric life into reality.”

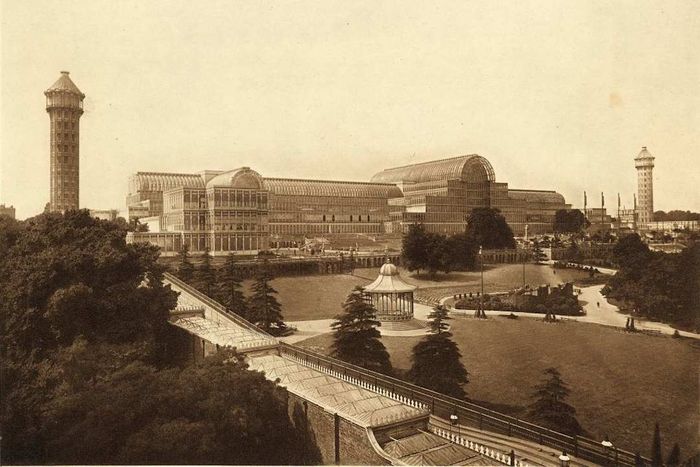

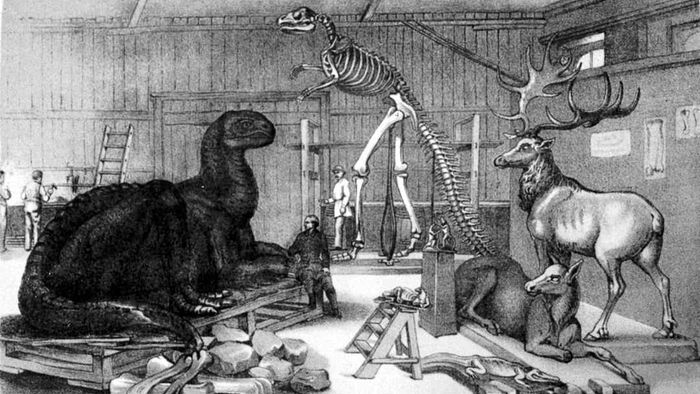

Crystal Palace arranged for Hawkins to have a studio on the premises, which was little more than a spacious shed surrounded by mud. One visitor described it as a “long, low, window-roofed building,” while another called it “rudely” constructed. Its true value, however, lay in the astonishing creations inside—described by a contemporary writer as a menagerie filled with “huge lizards, turtles, long-snouted crocodiles, and grotesque reptiles that resembled fish, frogs, and birds.”

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s “extinct animals” displayed in his workshop at Sydenham. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s “extinct animals” displayed in his workshop at Sydenham. | Print Collector/GettyImagesHawkins and a team of laborers used whatever materials they could find—including parts from an abandoned building—to construct the dinosaurs. Plaster molds were cast in clay; iron rods and bricks provided structural support, while concrete formed the exterior shells of the giant creatures.

Hawkins was resolute in his decision not to use pillars or supporting structures, even though these might have made the project easier. Instead, he likened the task to constructing four houses perched on stilts. As he later shared with an audience during one of his lectures:

“Some of these models contained 30 tons of clay, which had to be supported by four legs, as the natural history characteristics of these creatures didn’t allow me to use any of the usual methods for support that sculptors rely on in ordinary cases. I couldn’t use trees, rocks, or foliage to hold up those immense bodies. To make them natural, they had to be built directly on their four legs. In the case of the Iguanodon, this was akin to constructing a house on four columns, as the materials for the standing Iguanodon include four iron columns 9 feet long and 7 inches in diameter, 600 bricks, 650 half-round 5-inch drain tiles, 900 plain tiles, 38 casks of cement, 90 casks of broken stone, amounting to a total of 640 bushels of artificial stone.”

The laborers likely handled tasks like the bricking and pouring of concrete, though they worked from the clay molds created by Hawkins. He focused on the finer details, such as adding texture to the skin, nails, and teeth. Each dinosaur had concealed openings in its belly for practical purposes, whether to prepare them for display or for future repairs. These openings also facilitated water drainage. The models were then painted to provide color and detail.

Hawkins’s role extended beyond the four dinosaurs. A total of 33 animals were planned for Crystal Palace Park, most of which were much smaller in scale. Hawkins worked tirelessly from September 1852 to early 1855, adjusting plans for a mammoth and a giant tortoise as the budget tightened. Although Queen Victoria was charmed by his work, Hawkins still had to keep everything within financial limits.

“The newspapers of the time were supportive of Hawkins and criticized the funding cuts. They argued that it would have only taken a small additional amount of money to allow Hawkins to finish his mammoth,” Witton says.

As the project neared completion, Hawkins marked his creation by carving the inscription “B. Hawkins, Builder, 1854” on the lower jaw of one of the Iguanodons. However, Hawkins had another, even grander idea to claim as his own—an idea that would soon capture the attention of all of London.

Inside the Belly of the Beast

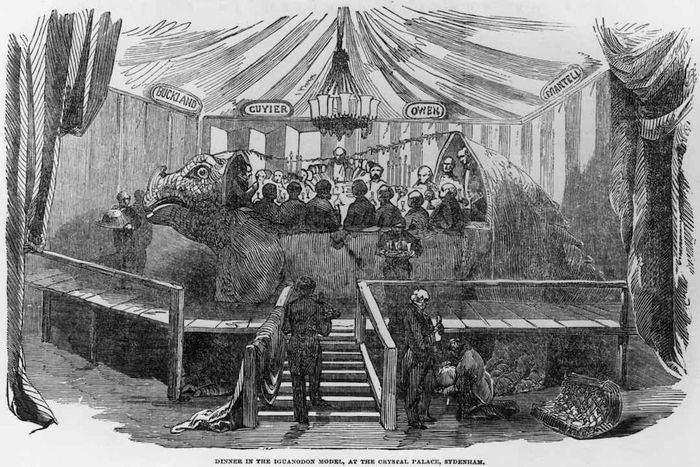

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins invited leading paleontologists to dine inside his dino. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins invited leading paleontologists to dine inside his dino. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesAs work continued on the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, the project’s organizers invited reporters—probably wishing they’d brought rubber boots—into the workshop. Depictions of Hawkins and his team at work were published in newspapers like The Illustrated London News, Punch, and others. The media buzz built excitement for the exhibit's grand unveiling, but nothing could compare to the spectacle Hawkins himself had orchestrated.

On New Year’s Eve of 1853, Hawkins hosted a lavish dinner for more than 20 distinguished scientists, journalists, and other notable figures inside one of the Iguanodon sculptures. While it’s unclear whether they dined in the actual model or one of its molds, the structure was modified to fit a table and chairs inside, with extra space for those who couldn’t fit within the model itself (the “slightly less important guests,” as Witton notes). Stairs were used to access the interior, where a sumptuous menu featuring fish, pheasants, and mock turtle soup awaited. Hanging above the guests were banners with the names of prominent paleontologists like William Buckland, Georges Cuvier, Gideon Mantell, and Richard Owen. Hawkins later described the setup as resembling a 30-foot-wide boot.

“Hawkins was quite adept at promoting himself in this way,” Peck says. “The dinner served partly as a thank-you to his mentors and financial backers, but it was also a publicity stunt. The press couldn’t resist such an unusual spectacle—celebrities dining inside a dinosaur! The event made headlines in newspapers, and it generated a huge amount of buzz. This only increased the public’s eagerness to visit the park and see the sculptures for themselves.”

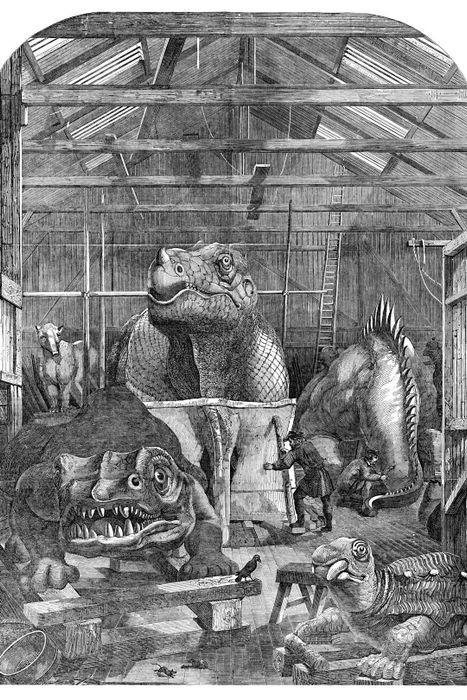

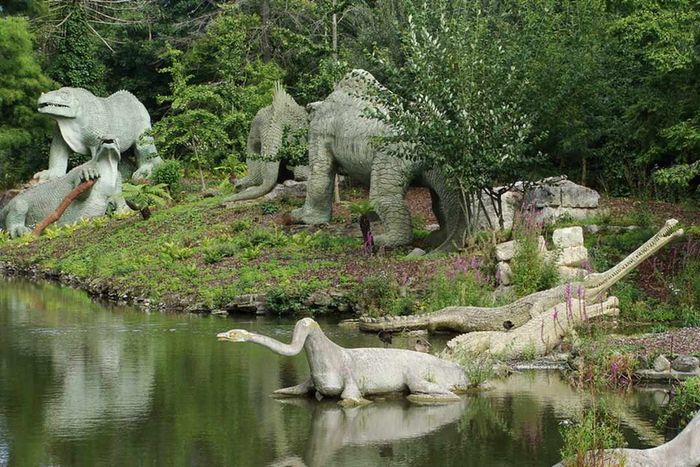

Two of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's dinosaur models in Crystal Palace Park | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Two of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's dinosaur models in Crystal Palace Park | Heritage Images/GettyImagesNaturally, Owen was present at the event, taking the place of honor at the head of the table. This positioning highlighted his foundational role in the field of dinosaur study, even though his direct involvement in the project was limited.

“He offered some initial guidance as the project progressed, but I doubt he was deeply involved,” Peck remarks. “Owen was playing it safe. There was so much uncertainty surrounding dinosaurs, and he didn’t want to risk his name being linked too closely with something that could later be proven inaccurate. Owen himself referred to Hawkins’s work as conjectural. Essentially, he distanced himself from the project, leaving Hawkins to bear the brunt of the responsibility.”

Owen’s concerns turned out to be unfounded. When Queen Victoria formally opened Crystal Palace Park in 1854, 40,000 spectators marveled at the spectacle. For the first time, a three-dimensional setting featured a collection of enormous dinosaurs towering over amazed onlookers. The dinosaurs were placed near a series of “geological illustrations” created by esteemed geologist David Thomas Ansted, all set against an artificial lake in a landscape designed by the renowned botanist and engineer Joseph Paxton.

“Of all the attractions in the second incarnation of Crystal Palace at Sydenham, the dinosaurs were by far the most talked-about and innovative,” Peck recalls. “People had already seen the other exhibits from the original Crystal Palace. But these dinosaurs—well, they were monumental. The atmosphere was light-hearted and whimsical. Children screamed in excitement, while the dinosaurs loomed ominously.”

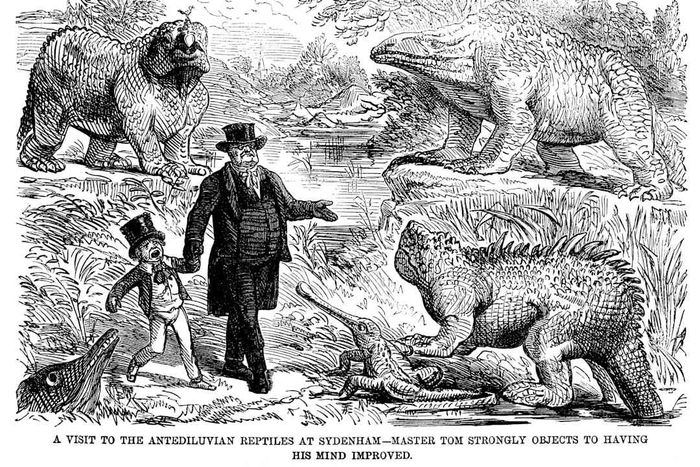

A cartoon of a Victorian boy terrified by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's creations | whitemay/iStock via Getty Images

A cartoon of a Victorian boy terrified by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's creations | whitemay/iStock via Getty ImagesFor many, it was an utterly bewildering experience. Unlike modern museums, there were no informative signs or panels to explain the exhibits, leaving the general public clueless about what they were witnessing. But Hawkins’s dinosaurs achieved something remarkable—they were making science accessible to all. In an era when scientific exploration was typically reserved for the wealthy elite, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs offered everyone, from royalty to the poorest street children, an opportunity to explore a previously hidden chapter of the Earth’s history.

“Hawkins didn’t hail from an upper-class background. He worked his way up,” Witton observes—and perhaps his own experiences shaped the way he communicated scientific ideas to the public.

Given their immense size, the logistics of transporting the dinosaur models from the shed to their final home in the park remain unclear. They were likely coated in additional plaster for protection and moved on sledges, although it’s possible some were assembled in sections. Once they reached their designated spots, concrete was poured to secure them. The largest models, weighing up to 30 tons, were likely finished on-site.

Despite facing financial and logistical challenges, Hawkins ignited a fascination with dinosaurs that would resonate throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. While the project didn’t pay well, it opened many doors for him. He went on to create smaller versions of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs for public sale and was soon invited to replicate his work in the United States. The success of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs would sustain him for the rest of his career.

What initially seemed like an invitation to America soon became an escape of sorts. That’s because Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins struggled to manage his angered wife. In fact, it was his two angry wives that ultimately drove him away.

An Extinct Marriage

Hawkins's Hadrosaurus | Frederic Augustus Lucas, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Hawkins's Hadrosaurus | Frederic Augustus Lucas, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe personal life of an artist can often be tumultuous, and Hawkins’s was no exception. He was married with 10 children, seven of whom survived past infancy. He wed Mary Green in 1826, when he was around 20 years old. Though they had four daughters and a son, their marriage began to fade within a decade. Then, Hawkins crossed paths with artist Frances Keenan, and soon he was spending the majority of his time with her. Without informing Mary, or even considering a divorce, he married Frances in 1836. For years, neither wife was aware of the other’s existence.

“I suspect his first wife began to grow suspicious as he spent years away from home. He traveled to Europe and Russia, initially justifying these trips as art-related ventures,” Peck observes. “Meanwhile, she remained at home, occupied with raising their children.”

When both of Hawkins’s wives learned of his bigamy, their anger was entirely predictable. Though the exact moment his double life was discovered remains unclear, Peck believes that Hawkins found it too simple to gather his belongings and head to the United States in 1868, where he was introduced with a letter of recommendation from Charles Darwin. The United States had no counterparts to the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. The Americans were eager to hear about his work, research, models, and how he might contribute to this rapidly growing field of study.

Hawkins was invited to deliver lectures where he discussed the construction of his models and engaged in a bit of theatrics, drawing large-scale animals on canvases so vast that ladders were needed to reach the top. He also took advantage of these occasions to express his anti-evolutionary views, which were partly influenced by Richard Owen's beliefs.

Perhaps Hawkins's most thrilling project in the United States was his work on Hadrosaurus, a nearly complete fossil discovered in 1858 that would become the first mounted dinosaur skeleton in history. Hadrosaurus lacked a head, so Hawkins crafted one, collaborating with Joseph Leidy from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia to erect the towering skeleton. This was an evolution of the wonders of Crystal Palace Park—lacking the charm of the replica creatures but gaining fascination for being based on a real fossil. The display attracted over 100,000 visitors in 1869, doubling the attendance of the previous year. To manage the crowds, the museum started charging admission—not to profit, but to slow down the influx of visitors.

Shortly after, Hawkins received an invitation from Central Park comptroller Andrew Green to recreate his Crystal Palace project in New York City. Green had envisioned a Paleozoic Museum, and a thrilled Hawkins began working on a new collection of prehistoric animals in a different—and presumably more pleasant—workshop, located where the future American Museum of Natural History would eventually stand. A 39-foot Hadrosaurus stood as the centerpiece, a replica of the one Hawkins had constructed in Philadelphia.

A glimpse into Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's Central Park studio | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A glimpse into Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's Central Park studio | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe Paleozoic Museum, however, never came to fruition. Hawkins encountered resistance from William “Boss” Tweed, the powerful and corrupt leader of Tammany Hall, who controlled city politics. When Tweed realized he wasn’t getting his usual cut from such a profitable project, “he shut down the Central Park Commission and the funding for the Paleozoic Museum,” says Peck. “Hawkins wasn’t familiar with American politics. He thought if he just kept working on the project, the money would eventually follow. He thought he could sell the idea to other institutions. But Tweed was furious when Hawkins persisted.”

Hawkins openly criticized Tweed, a decision that backfired. On May 3, 1871, Tweed sent his men to Hawkins’s workshop, where they destroyed his in-progress dinosaur models, wiping out years of work. Valuable materials like iron were salvaged from the wreckage, but the rest was discarded or buried, fueling urban myths about the dinosaur heads becoming the mounds in the park’s baseball fields.

Just six months later, Tweed’s corrupt empire came crashing down, and he was imprisoned for the rest of his life. As Peck notes, “If the timing had been different, if Tweed had been arrested first, we might have had the first paleo museum in America, right there in Central Park.”

Yet, the damage to the dinosaurs had been done. Hawkins accepted a position at the Elizabeth Marsh Museum of Geology and Archaeology at the College of New Jersey, now known as Princeton University, where he painted detailed illustrations of dinosaurs—including Iguanodon—and built a lasting relationship with the institution. Meanwhile, he continued to support his two families back in the UK, forcing him to live modestly. He passed away in 1894, with much of his contribution to paleontology remaining overlooked.

In some of his later paintings for Princeton, Hawkins incorporated the growing understanding of paleontologists. His original depictions of Iguanodons and Megalosaurus, which were once shown on all fours, were reworked after scientists discovered these creatures were actually bipedal. This willingness to revise his work—reflecting a rare openness to self-correction for that era—marked a significant shift in his approach.

“There was a desire to respect his work at Crystal Palace without completely discrediting it by making drastic changes, but at the same time, he couldn’t ignore the progress of science,” says Witton. “He needed to present them as bipedal, yet he depicted one crouching over a dead Iguanodon, still using all four limbs to support itself.”

However, in the years that followed, Hawkins was met with more criticism than praise for his efforts.

Challenges of Scaling Up

Two workers making final adjustments to a dinosaur model by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. | Fox Photos/GettyImages

Two workers making final adjustments to a dinosaur model by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. | Fox Photos/GettyImages“It’s like attempting to build a LEGO model without instructions and with three-quarters of the pieces missing.”

Susannah Maidment, a senior researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, discusses the monumental challenges Hawkins faced in his pursuit of anatomical precision. “For Iguanodon, only limb bones were available,” Maidment explains. “We didn’t have a complete skeleton or anything articulated—no vertebrae. For Hylaeosaurus, even today, only a single known specimen exists. It’s a slab with some vertebrae, pectoral girdles, and plates. For Megalosaurus, there were some limbs and a lower jaw.” The first complete Iguanodon skeleton wasn’t discovered until 1878, when one was found in a Belgian coal mine. Many more fossils have been found disarranged, having been washed away by rivers or buried in ancient mudslides, with the bones jumbled up in newer materials.

Hawkins crafted his dinosaurs using the best available knowledge of the time—knowledge that was quickly surpassed by subsequent discoveries. Skeletons of Brontosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops were excavated, leading to a deeper understanding of dinosaurs that Hawkins never could have imagined at the peak of his career.

When designing the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, Hawkins made educated guesses about everything from skin texture to color by drawing comparisons with living reptiles. Megalosaurus likely had a thicker skull, not the long crocodile-like head he sculpted. Hylaeosaurus was probably spiked along its back and sides, not its spine. Iguanodon is now believed to have had a quadrupedal stance, walking on its hoof-like fingers, meaning the four-legged Iguanodon in the park wasn’t entirely accurate. The spike Hawkins placed on Iguanodon’s nose actually belonged on its hands.

Detail of the leg of one of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's dinosaurs. | Carzylegs14/iStock via Getty Images

Detail of the leg of one of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's dinosaurs. | Carzylegs14/iStock via Getty Images“It’s important to view it in its historical context. You can’t critique artwork and judge its scientific accuracy by today’s standards. It was based on the knowledge they had at the time,” says Witton. “I’ve been fortunate enough to examine them closely and appreciate the details. They’re covered in fascinating and carefully designed textures. You can see scales, smooth skin, folds. The musculature is well-defined. This is especially noticeable on Iguanodon. The shoulder muscles bulge. The belly protrudes. The stomach area of the standing one differs from the one sitting down.”

“He was meticulous in his modeling. I can still look at them and think, ‘Wow, that really resembles a real creature.’”

When Hawkins wasn’t certain about a dinosaur’s physical appearance, he cleverly disguised his doubts through the way he positioned them in dioramas. Hylaeosaurus, for example, is shown facing away from visitors, possibly because Hawkins wasn’t entirely sure what it should look like.”

Over time, admiration for Hawkins’s artistry shifted to condescension. Rather than acknowledging his accomplishments, critics focused on his mistakes. A lot of the criticism, according to Peck, was aimed at Richard Owen, whose anti-evolution stance and pompous attitude made him unpopular with the newer generation of scientists.

“It’s easy to mock it from today’s perspective,” he says. “The silver lining is that no one ever took down the dinosaurs at Sydenham. They were too beloved. But had they been housed in a proper science museum instead of a park, they might have been taken down or even dismantled as new scientific insights emerged.”

Where Dinosaurs Roam

Two of Hawkins's dinosaurs in Crystal Palace Park, Sydenham | fiomaha, Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0

Two of Hawkins's dinosaurs in Crystal Palace Park, Sydenham | fiomaha, Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0Ellinor Michel frequently overheard it. As she wandered around the dinosaurs in Crystal Palace Park during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, she listened to children and adults marveling at the models. The youngsters gazed up at the creatures that had once sparked excitement in Victorian youth, only to later be dismissed as outdated. They told each other that the dinosaurs were from the 19th century and emphasized their significance.

Michel, a paleontologist, chairs the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, a non-profit organization dedicated to conserving the models and enhancing their public visibility. Alongside Mark Witton, she co-authored *The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs*, an extensive history of the exhibit. She first encountered the dinosaurs when she relocated to London from the United States 25 years ago.

“You could just walk right up and view them! It was incredible. They had endured for 170 years,” Michel recalls to Mytour. “That was where it all began.”

By “it,” Michel refers to the efforts to preserve the dinosaurs. Along with her colleague, friend, and science historian Joe Cain, Michel became a passionate advocate for the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. “We have two main objectives,” Michel explains. “One is the preservation of the site and the sculptures. The other is enhancing the public understanding of the site and sculptures. These goals support each other. The public appreciates their significance, which grows as the site improves.” (The London Borough of Bromley owns the dinosaurs, and the Friends group acts as their caretakers.)

A collection of Hawkins's creations | Ben Saunders, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

A collection of Hawkins's creations | Ben Saunders, Flickr // CC BY 2.0Thanks to Hawkins’s expert craftsmanship, the dinosaurs have remained largely intact since their unveiling in 1854. Through paint layer analysis, Michel discovered that city officials regularly applied fresh coats of paint every five or six years. However, in recent decades, maintaining and repairing the sculptures has become increasingly difficult.

“Vegetation is growing on them. Cracks are appearing in the skin. Plants are forcing them apart,” Michel explains. “The island they sit on isn’t natural—it was artificially created for them. There are issues like land slumping and more.”

In the Victorian era, Hawkins’s dinosaurs were able to transport viewers into a world of suspended disbelief—but that illusion fades when a jaw falls off and the rusted framework is exposed, Witton observes. “It begins to look like a gravely injured animal. It’s hard not to feel a sense of compassion,” he says.

Michel established the Friends group in 2013 with local residents after witnessing the models suffer from weather damage, vandalism, and the dangers of Instagram. “They’re perfect for selfies, but they’re 170 years old and deteriorating. Climbing on them only causes more harm,” Michel points out.

In May 2021, the face of Megalosaurus was restored after suffering damage in May 2020, though the dinosaurs still await a much-needed, comprehensive renovation. The last major renovation took place two decades ago, after a vandalism incident. The sculptures were repaired, the geological illustrations were overhauled, and elements in the tableau were rearranged for greater historical accuracy. “I hope we’re on the verge of another significant restoration,” says Michel.

A Hawkins dinosaur at Crystal Palace Park | Ian Wright, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0

A Hawkins dinosaur at Crystal Palace Park | Ian Wright, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0In February 2020, the site was granted the important Heritage at Risk status by Historic England, the government body responsible for heritage conservation, prioritizing the dinosaurs for future funding. The dinosaurs also hold Grade I-listed monument status, a designation reserved for sites of exceptional historical importance (only 2.5 percent of the UK's listed structures are given this honor).

“We wanted to be included on the at-risk register. It provides more momentum and increases the likelihood that the work will actually happen,” Michel explains.

The at-risk designation reinforces the notion that Hawkins’s work was a cornerstone in the emergence of paleoart and marks a pivotal point not only in paleontology but in how new scientific discoveries were communicated to the public. They capture a distinct moment in history when the Victorian public first encountered the mighty reptiles of prehistory.

“Crystal Palace marked the first instance when all the elements of modern paleoart were brought together. It was a public-facing, commercial endeavor; an artist collaborated with a scientist, and they were as up-to-date as possible,” explains Witton. “Before this, paleoart was much more vague. Artists would sketch generalized, monstrous reptiles and call it a day. This was the first time paleoart’s potential was showcased. It demonstrated what paleoart could achieve.”

Hawkins can be seen as a trailblazer in edutainment, blending intellectually enriching content with entertainment in a way that wrapped science in the guise of fun. It may not be a direct line, but there’s an undeniable connection between Hawkins and figures like Bill Nye, Mr. Wizard, and the various science learning centers that followed.

While Hawkins’s name might not be widely recognized today, his legacy in raising awareness of prehistoric life and making it accessible to people from all walks of life is still vital. Even today, visitors are in awe of the dinosaurs, captivated by the artistic ideas that may never have been accurate but were made convincing by Hawkins’s vision.

“When you visit, you’re seeing how people imagined prehistoric animals in the 1850s,” says Witton. “Few places in the world offer such a grand and educational experience of that era’s interpretation of prehistoric life.”