The horse botfly (Gasterophilus intestinalis), resembling a bumblebee, is most active during the summer months. Image credit: JanetGraham/Flickr/(CC BY 2.0)

The horse botfly (Gasterophilus intestinalis), resembling a bumblebee, is most active during the summer months. Image credit: JanetGraham/Flickr/(CC BY 2.0)Parasites are truly intriguing—once you get past the "yuck" factor. For example, did you know that a beef tapeworm can reach lengths of up to 82 feet (25 meters)? Or that the spiny Pomphorhynchus laevis parasite inspired the development of a new type of surgical microneedle patch? Incredible.

However, it's best to avoid botflies. These insects reside inside mammalian hosts during their larval phase. One variety, known as Dermatobia hominis or the "human botfly," specifically targets humans, though it's not the only species that makes our bodies their temporary homes.

Removing botfly larvae is a task best handled by professionals. You might be surprised by the tools people use to remove these parasites.

Botflies Everywhere

Experts categorize botflies as "true flies," meaning they belong to the insect order Diptera, which translates to "two wings" in Greek. While some Dipterans are flightless, those that can fly only have one pair of wings, unlike the four wings of butterflies or grasshoppers.

There are around 160 botfly species scattered across the globe, most of which are found in the Western Hemisphere. They are highly specialized. For instance, the rhinoceros botfly — the largest fly species in Africa — targets white and black rhinos as hosts for its larvae. Other botflies have adapted to parasitize horses, camels, cattle, reindeer, and various rodents.

Typically, adult botflies remain close to their preferred host species. However, the larvae can survive on alternative hosts if necessary, although this often ends poorly for one of the parties involved.

Take the North American woodrat botfly, for example. Typically, this creature lays its larvae in native pack rats and eastern woodrats. However, recently, the botfly has begun infecting roof rats — an invasive species brought over by human settlers. Researchers have discovered that the larvae cause significantly more tissue damage when they develop inside roof rats, compared to native rats.

On the other hand, botfly larvae raised in non-native hosts don't always make it to adulthood. C'est la vie.

Bringing the Goods

Before any larvae can emerge, the eggs must be deposited in the proper location. The preferred nesting site differs depending on the species.

Horse botflies attach their fresh eggs to strands of hair on passing horses. Once the host licks them off, the larvae hatch and quickly settle inside the horse's mouth. From there, they travel into the stomach. As they cling to the gastrointestinal tract, the parasites gradually mature into pupae, which exit through the anus, bury themselves in soil (or feces), and transform into adult flies. (We apologize if you’re reading this around lunchtime.)

Other botflies take a more indirect approach. Species that target rodents prefer to deposit their eggs in the dens or nests of potential hosts. Then there are the shortcutters. For example, the sheep botfly doesn't lay eggs at all — they hatch inside the mother’s body. Once that process is complete, the mother insect places her young on a sheep's nose to start their journey.

Meanwhile, our old friend, the human botfly, prefers to outsource.

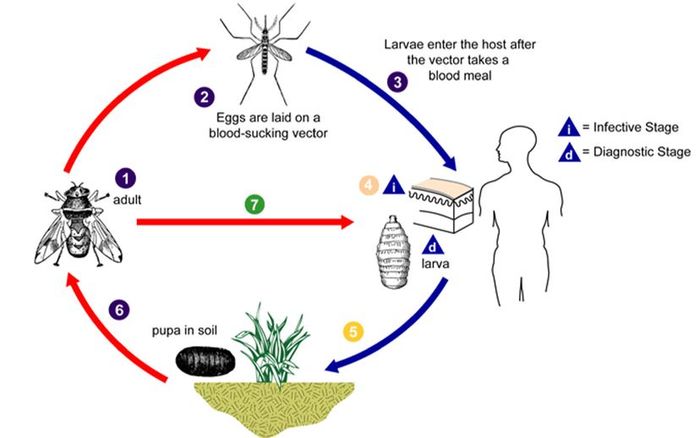

This illustration from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control depicts the fundamental life cycle of the human botfly.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control

This illustration from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control depicts the fundamental life cycle of the human botfly.

U.S. Centers for Disease ControlHuman Victims

The human botfly, native to Central and South America, closely resembles an ordinary bumblebee. However, don’t expect to see it gracing the cover of a cereal box anytime soon. Adults range from 0.47 to 0.71 inches (12 to 18 millimeters) in length, with orange legs and blue-gray abdomens.

The lifecycle of the botfly begins when a female attaches her eggs to a passing tick or mosquito. After securing her eggs to the bloodsucker’s belly, she releases it — none the worse for wear. However, when that mosquito bites a human, the body heat triggers the botfly’s eggs to hatch. The larvae then dive into the bite wound or an open hair follicle.

The larvae burrow face-first under the skin, creating small holes for themselves. They feed on proteins, dead cells, and fluids secreted from pores or inflamed wounds. During this time, the larvae position their rear ends at the top of the hole, as they breathe through two openings called "spiracles" at their hindquarters.

Feeding is interrupted by a series of molts. About 30 days after their arrival, the larvae grow strong enough to crawl out backward, break free from the host, and bury themselves underground — where they will eventually metamorphose into adult flies.

Extraction Techniques

So, having hungry larvae burrow into your skin isn't exactly a pleasant experience. Who would've guessed, right?

The unlucky humans hosting these botflies may experience what's been described as "intermittent stabbing pains" as the larvae twist and turn. This is because the parasites wriggle around aggressively when the host takes a shower or goes for a swim. One victim, a young girl, began hearing strange chewing noises after a botfly embedded itself near her ear.

By the way, human botflies aren't the only ones that can invade your body. Equestrians who neglect proper hygiene with their animals are at risk of being infected by horse botflies. Additionally, sheep and reindeer botflies have also been known to find their way into unsuspecting humans.

If you happen to discover botfly larvae inside you, resist the urge to remove them yourself. The larvae are coated with tiny sharp spikes that help them anchor to your tissues, and trying to pull them out recklessly can break them apart, leading to infection.

Ideally, a medical professional should remove the pests using anesthesia and a scalpel. However, if that's not possible, alternative methods can be employed. Some doctors use blunt instruments to apply pressure around the botfly’s hole, forcing it out. Once the larvae are removed, the wound typically requires daily cleaning, but there are generally no other lasting effects.

Another method to expel the larvae is by cutting off its air supply. By blocking the spiracles with a solid object, the larva should eventually leave the host on its own. As strange as it sounds, pressing a piece of bacon or steak onto the wound often does the trick. Who ever said red meat’s bad for you?

Sue, the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton ever discovered, has a series of lesions on her lower jaw. Paleontologists believe these marks were caused by a parasitic infection, suggesting even massive 40-foot (12.3-meter) dinosaurs weren't immune to bodily invaders. Hope that brings you some comfort.