Pregnancy Picture Collection: While some men, like this individual in Beijing, China, go to great lengths to understand the experience their wives endure during pregnancy, others have no choice but to join in. Explore more pregnancy photos.

China Photos/Getty Images

Pregnancy Picture Collection: While some men, like this individual in Beijing, China, go to great lengths to understand the experience their wives endure during pregnancy, others have no choice but to join in. Explore more pregnancy photos.

China Photos/Getty ImagesDuring pregnancy, men often take a backseat. After all, it's the women who carry the baby and face the trials of labor and delivery. Most men are eager to assist, whether it’s running out late at night to grab cravings like French fries and a chocolate shake for their wives. But for some, showing support is just the beginning of their involvement.

Picture yourself experiencing bloating in sync with your wife’s growing belly or both of you battling morning sickness together. Until recently, medical professionals often dismissed reports of expectant fathers experiencing symptoms such as food cravings, back pain, and even weight gain. However, a 2007 study did much to confirm the existence of Couvade syndrome, or sympathetic pregnancy.

The research, conducted at St. George's Hospital in London, examined 282 men aged 19 to 55 whose wives were expecting. A separate group of 281 men with non-pregnant wives served as the control group. The study found that a majority of men with pregnant wives displayed a range of pregnancy-related symptoms, including mood swings and morning sickness.

Stomach cramps were the most frequently reported symptom; one man even described experiencing labor pains that rivaled his wife's while she was giving birth. A few men showing signs of sympathetic pregnancy also developed pseudocyesis, a condition where they experienced a phantom swollen belly.

The study revealed that the symptoms typically followed a similar timeline to the pregnancies of the men's wives. They began in the early stages, peaked during the third trimester, and gradually faded away once the wives had given birth. Even more bizarrely, 11 of the men who sought medical attention for their symptoms found that doctors could offer no physical explanation for their discomfort.

Couvade syndrome (derived from the French word 'couver,' meaning 'to hatch') has been well documented around the world. A 1994 study showed that Thai men also exhibited signs of sympathetic pregnancy. Another study in Italy the following year found that the incidence of sympathetic pregnancy ranged from 11 to 65 percent [source: Klein]. What's even more intriguing is that you don't have to be a man with a pregnant wife to experience Couvade syndrome. In one documented case in the U.S., a woman began to display symptoms similar to her pregnant twin sister who lived in a different city [source: Budur, et al.].

But what causes this phenomenon? Researchers are still unsure, though several theories have been proposed. One suggestion is that a man's anxiety about the impending birth of his child could trigger symptoms of sympathetic pregnancy. Another theory posits that Couvade syndrome may be a man's 'statement of paternity' or possibly a sign of envy toward his wife or rivalry with the baby [source: Klein].

These theories point to Couvade syndrome potentially being a psychosomatic condition—a response of the body to mental stimuli. Discover more about the intriguing connection between mind and body on the next page.

Psychosomatic Conditions

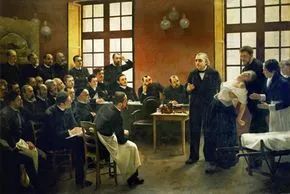

The exploration of psychosomatic illnesses began with the study of hysteria, led by physicians like Jean Martin Charcot, seen here teaching about the condition.

Imagno/Getty Images

The exploration of psychosomatic illnesses began with the study of hysteria, led by physicians like Jean Martin Charcot, seen here teaching about the condition.

Imagno/Getty ImagesCurrently, Couvade syndrome isn't recognized as an official medical condition, although the St. George's University study has helped validate its potential existence. It seems plausible that the syndrome might be understood as the body reacting to emotional states, and the next step is to uncover the connection between mind and body, though this link has proven difficult to pinpoint.

It wasn't until the 18th century that serious inquiry into how the mind influences physical ailments began. European physicians investigating female hysteria (once thought to originate in the uterus) concluded that it was a medical condition that resulted from heightened emotional states. Since then, research into psychosomatic disorders has ebbed and flowed but has never ceased.

Psychosomatic disorders can manifest in various ways. For example, it can be perceived as purely a mental issue, like in the case of Munchausen syndrome, where a person believes they are ill to attract attention. Though the symptoms are entirely in the mind, they can feel very real to the individual. It may also appear as the result of fear or anxiety, as seen in conversion disorder, where emotional distress physically manifests, such as when a dancer, fearing to perform, becomes paralyzed [source: Mayo Clinic].

There is another perspective on psychosomatic conditions that doesn't necessarily imply mental illness. Medicine is increasingly acknowledging the significant impact the mind has on an individual's overall health.

Psychosomatic conditions can range from something as simple as stress leading to a headache to something as complex as an introverted personality possibly contributing to the development of cancer. Numerous studies have demonstrated a link between emotions and physical illness. For instance, one study discovered that individuals with panic disorder are more likely to exhibit abnormal heart function. Other research has shown that patients who experience depression after major surgery have a higher likelihood of dying compared to those who maintain a positive outlook during the same procedures.

As research continues to explore the relationship between emotional states and physical health, the actual mechanisms at play are still being studied. Like Couvade syndrome, it’s clear that the mind can influence the body. However, science is not one to settle for mere correlation.

Endocrinology may offer the best explanation for the connection between the mind and body. For years, scientists have understood that hormones influence both mood and physical functions. For example, emotional distress is linked to the release of the hormone 17-OHCS by the adrenal glands. The link here could be that emotional stress, like anxiety, impacts the central nervous system, which in turn affects the endocrine system’s functionality.

As scientific exploration of how emotions influence physical health deepens, the connection between the mind and body becomes more apparent. This connection appears to be bidirectional: just as emotions affect glands, studies have also found that electrolytes — like potassium, which generate the electrical impulses necessary for body function — are connected to mental health conditions such as depression. In the future, research like this may help explain phenomena like sympathetic pregnancy.

For additional insights into the connection between pregnancy and the mind, continue reading on the next page.