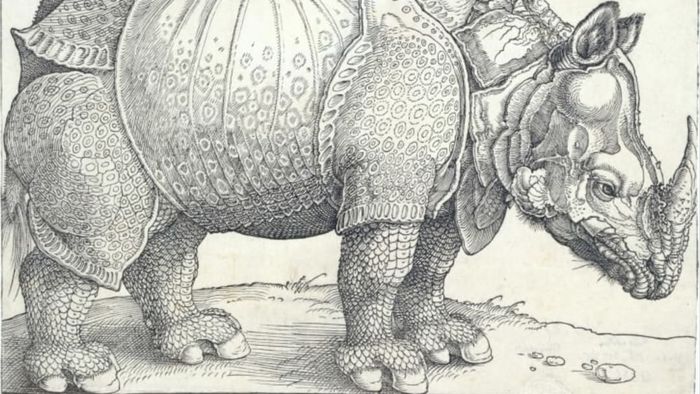

For over two centuries, Europeans imagined the rhinoceros more as a mighty force than a living creature. This misconception was not without reason, as rhinos were unseen in Europe, and the famous 1515 woodcut by Albrecht Dürer became the definitive image of the animal for Europeans. The print, based solely on a written description, depicted a rhinoceros in profile, almost as if it were prepared for battle, with a horn misplaced on its back. The German inscription atop the print was derived from an account by the Roman author Pliny the Elder, who described the rhinoceros as 'fast, impetuous, and cunning,' dubbing it 'the mortal enemy of the elephant.'

Albrecht Dürer, The Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public Domain

Albrecht Dürer, The Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public DomainThe story shifted dramatically in July of 1741, when a real rhinoceros arrived in Rotterdam. Named Miss Clara, this Indian rhinoceros sparked nearly two decades of 'rhinomania' as she toured Europe. She charmed aristocrats in Europe's grand courts and captivated the common folk in small villages. Across France, Italy, Germany, England, Switzerland, and Austria, artists immortalized her tough hide and serene eyes, creating clocks and commemorative medals in her likeness. Poets composed verses about her, and musicians created songs in her honor. In Paris, women styled their hair in the 'à la rhinocéros' fashion, with ribbons or feathers designed to resemble a horn on their heads. Clara was a sensation wherever she went.

Her journey began in 1738 when her mother was killed in India. As a young rhino, she became a pet to Jan Albert Sichtermann, a director of the Dutch East India Company, at his estate near what is now Kolkata. However, she soon grew too large for such a domestic life [PDF]. In the 2005 book Clara's Grand Tour: Travels with a Rhinoceros in Eighteenth-Century Europe, Glynis Ridley details how Dutch sea captain Douwemout Van der Meer acquired Clara in 1740. After a long journey from India to the Netherlands, Van der Meer managed to keep her alive far beyond the usual lifespan for captive rhinoceroses, despite feeding her large amounts of beer. He became her caretaker, manager, and dedicated promoter.

“If Van der Meer had left behind a journal, future generations could have observed firsthand his struggles with the complexities of owning and transporting the heaviest land animal on earth,” Ridley writes in Clara’s Grand Tour. “The nature of these difficulties is evident in a 1770 account of an attempted transport of a rhinoceros across France. For a single trip moving a male rhino from Lorient to Versailles, the French government funded two days of carpenters, 36 days of locksmiths, 57 days of blacksmiths, and 72 days of wheelwright labor. (Despite all this effort, the wagon still collapsed during the journey, and additional labor was required to get the rhino back on the road.)”

In other words, many rhinos traveling across Europe didn’t fare well. The rhinoceros depicted in Dürer’s woodcut drowned in a 1516 shipwreck off Italy's coast. A rhinoceros brought to Lisbon in 1579 only lived a few years. Some reports claim that after it tipped over a royal carriage in Madrid, its eyes were gouged out. However, Van der Meer made sure Clara’s travel schedule allowed for adequate rest, and although he used a media strategy of posters to publicize each of her stops, he took great care with her journeys. For example, Clara was never led by a ring in her nose, a common practice with large animals like bulls, and she traveled from city to city in a massive wooden coach pulled by eight horses.

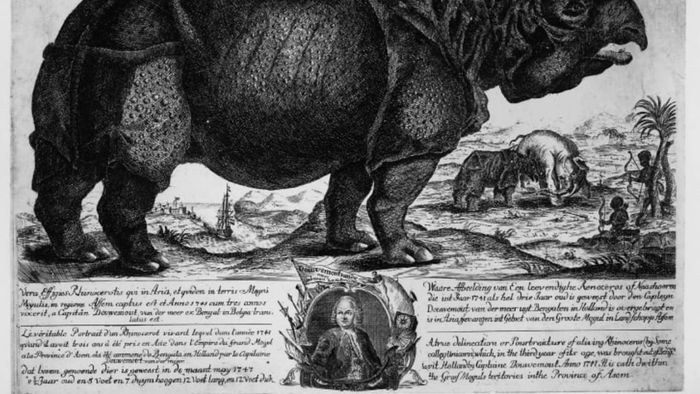

H. Oster, Wikimedia // Public Domain

H. Oster, Wikimedia // Public DomainFrom bronze sculptures to porcelain curios, Clara was celebrated in art at a level typically reserved for royalty. In a life-size 1749 portrait by the French artist Jean-Baptiste Oudry, she stands proudly in a pastoral setting. A 1747 etching (above) shows her in front of a vast background where dark-skinned figures, palm trees, and a scene of a rhinoceros goring an elephant underscore her exotic allure. A 1751 painting by Pietro Longhi, now housed at the National Gallery in London, features a group of masked Venetians observing Clara. One woman wears a Moretta mask, known as a “mute mask” because it lacks a mouth, and seems to be gazing directly at the viewer rather than at the celebrity animal, perhaps questioning who the true exhibit is.

Clara made her way into a significant 18th-century anatomical atlas: Bernhard Siegfried Albinus's 1747 Tabulae Sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. The illustrator, Jan Wandelaar, was one of the first artists to depict Clara and thus one of the pioneers in presenting a scientifically accurate rhinoceros. In two engravings, Clara stands behind flayed corpses, with both her and the dissected human bodies symbolizing the forefront of anatomical knowledge.

Jan Wandelaar, Wikimedia // Public Domain

Jan Wandelaar, Wikimedia // Public DomainClara passed away in April 1758 in London, two decades after being captured in India. While wild rhinoceroses typically live into their thirties, and those in captivity a bit longer, Clara far outlived the typical lifespan for such animals and traveled much more extensively than was common for exotic creatures in the 18th century. Strangely, despite her fame, the exact cause of her death remains unknown, and no record exists of what happened to her remains. There was also no reported public mourning for this global sensation. Yet through the art and memorabilia that endure, we can still see how Clara dramatically shifted Europe's perception of what a rhinoceros could be.