For those deeply invested in genetics, understanding start codons, stop codons, and a wide range of DNA-related terms is crucial. Yuichiro Chino / Getty Images

For those deeply invested in genetics, understanding start codons, stop codons, and a wide range of DNA-related terms is crucial. Yuichiro Chino / Getty ImagesIf you're exploring genetics, molecular biology, or a similar discipline, chances are you'll need to master reading a codon chart (also referred to as a codon table) to gain a clearer insight into the genetic code.

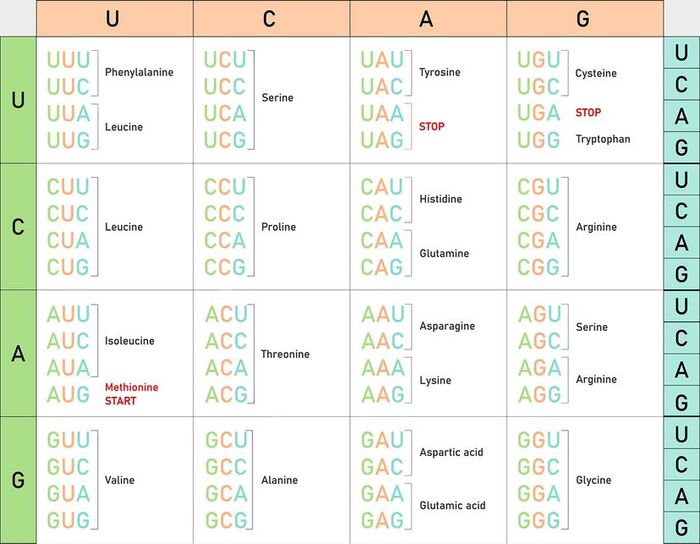

This chart showcases every possible codon — fundamental units of DNA and RNA — and the corresponding amino acids they encode. Utilizing a codon table allows you to convert genetic data into precise proteins. Let's delve deeper into the mechanics of this process.

The Genetic Code and Codons

Grasping the fundamentals of genetics is essential before diving into the use of a codon table.

The genetic code comprises the rules that guide the translation of information stored in genetic material (DNA or RNA) into proteins within living cells. This code is universal, applying uniformly across all life forms, from simple bacteria such as E. coli to more complex eukaryotes. (Eukaryotic cells feature a membrane-bound nucleus).

Codons, which are sequences of three nucleotides (a particular kind of organic molecule), represent the genetic code. Scientists denote the nucleotides in these triplet codes with the letters U, C, A, and G, representing uracil, cytosine, adenine, and guanine — the four nucleotides found in messenger RNA.

Take, for instance, an mRNA sequence like: AUG-GGU-CAA-UAA. Each of these codons is linked to a particular amino acid.

With four distinct nucleotides available, the total number of possible codons amounts to 64.

What Is a Codon Chart?

A codon chart serves as a visual tool that links each of the 64 codons to their respective amino acids or signals. Codon charts, or codon tables, typically come in two main formats: one is square or rectangular, and the other is circular.

Deciphering an mRNA sequence into a sequence of amino acids, the fundamental components of proteins, relies heavily on the use of a codon table.

To interpret a codon chart, begin on the left (green) to locate the first nucleotide in the sequence, proceed to the top (orange) for the second, and then to the right (blue) for the third. This method helps pinpoint the amino acid associated with that specific sequence.

artemide / Shutterstock

To interpret a codon chart, begin on the left (green) to locate the first nucleotide in the sequence, proceed to the top (orange) for the second, and then to the right (blue) for the third. This method helps pinpoint the amino acid associated with that specific sequence.

artemide / ShutterstockCodons and Their Matching Amino Acids

A codon table enables you to identify which amino acids match specific codons and vice versa. For instance:

- The amino acid asparagine (Asn) is represented by AAU and AAC.

- The amino acid glutamine (Gln) is linked to CAA and CAG.

- The amino acid glycine (Gly) corresponds to GGU, GGC, GGA, and GGG.

- The amino acid methionine (Met) is encoded by AUG.

- The amino acid phenylalanine (Phe) is encoded by UUU and UUC.

- The amino acid proline (Pro) is associated with CCU, CCC, CCA, and CCG.

- The amino acid valine (Val) is represented by GUU, GUC, GUA, and GUG.

Redundancy and Multiple Codons

The genetic code is characterized by redundancy, meaning several codons can represent the same amino acid. For instance, alanine is encoded by GCU, GCC, GCA, and GCG. This redundancy acts as a protective mechanism against genetic mutations, as changes in the third nucleotide frequently do not affect the amino acid produced.

How to Use a Codon Chart

Understanding how to interpret a codon chart allows you to identify the amino acids specified by a DNA sequence. Follow these steps:

- Determine the mRNA sequence. An mRNA sequence consists of codons transcribed from DNA. Consider the example mRNA sequence: AUG-GGU-CAA-UAA.

- Find the start codon. The start codon, usually AUG (methionine), marks the beginning of the protein synthesis process.

- Decode the codons into amino acids. Use the codon table to translate each codon into its respective amino acid.

- Stop at the stop codon. Translation halts when a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) is reached, indicating the end of the protein synthesis sequence.

Origins of the Codon Table

The codon chart emerged from the pioneering efforts of molecular biologists in the mid-20th century. The revelation of DNA's double-helix structure by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953 paved the way for decoding how genetic information is stored and translated into proteins.

During the early 1960s, Marshall Nirenberg (later awarded a Nobel Prize for his contributions to the genetic code) and Johannes Matthaei performed experiments using synthetic RNA to guide protein synthesis in cell-free environments.

Their research confirmed that particular codons match specific amino acids, leading to the identification of the first codon (UUU for phenylalanine). This milestone established the groundwork for the comprehensive codon table.

Subsequent studies by Nirenberg, Philip Leder, Har Gobind Khorana, and others built on this discovery. Khorana's contributions, especially his use of synthetic RNA with defined sequences, were crucial in mapping the remaining codons.

By 1966, researchers had fully unraveled the genetic code, uncovering that most amino acids are represented by multiple codons, a feature referred to as redundancy or degeneracy.

Significance in Biology and Medicine

In molecular biology, the codon chart has empowered scientists to investigate gene expression, regulation, and mutation processes, facilitating cross-species comparative studies. In medicine, it plays a pivotal role in advancing genetic research and creating therapeutic solutions.

In genetic science, the codon chart allows researchers to modify genes for studying disease mechanisms or producing therapeutic proteins. For example, recombinant DNA technology, which depends on the codon chart, has enabled the production of insulin, growth hormones, and other vital biological compounds.

The chart is also essential in gene therapy development, where faulty genes are corrected or replaced to treat genetic disorders.

Understanding codons aids scientists in designing mRNA vaccines, such as those developed for COVID-19. By optimizing codon sequences for efficient protein expression in human cells, researchers can enhance vaccine efficacy.