As a kid with a Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), I often ran into situations where my games wouldn’t load. But like every other kid, I knew the trick: remove the cartridge, blow on the contacts, and then slide it back in. And more often than not, it worked. (If it didn’t, I’d just keep trying until it did.) But in hindsight, did blowing on the cartridge really make a difference? I’ve spoken with experts, reviewed a study on this very topic, and now I have the answer. But before we dive into that, let's explore some technical details.

Famicom, NES, and the Zero Insertion Force Mechanism

The Nintendo Family Computer, aka Famicom. | Staffan Vilcans, Flickr // CC by SA 2.0

The Nintendo Family Computer, aka Famicom. | Staffan Vilcans, Flickr // CC by SA 2.0The NES released in the U.S. had a distinct look compared to Nintendo's original Famicom in Japan. The Famicom (short for Family Computer) is pictured above—it had a top-loading design where you inserted the cartridge into a slot on top. (It also sported a striking red-and-cream color scheme that, to me, resembles Voltron.) By placing the cartridge in from the top, the Famicom’s label became a kind of advertisement, showcasing the game being played. When Nintendo developed the NES for the U.S., they made a major change by placing the cartridge slot deep inside a gray VCR-like box (shown below). While the technology remained similar, the design was more like a VCR—a familiar, “modern” piece of equipment—intended to set the NES apart from older consoles like the Atari 2600. Nintendo aimed to be new, and better—so it concealed its slot.

Nintendo sought to incorporate a 'Zero Insertion Force' (ZIF) connection—a term that sounds like an awkward joke about relationships, but is actually a legitimate engineering concept. A ZIF connection means the user doesn’t have to apply pressure to insert the cartridge into the connector—there’s no 'insertion force' required. This is beneficial from an engineering perspective because excessive force can damage connectors over time. A typical VCR from the mid-to-late 80s used a form of ZIF design: you’d place the tape in the front, and the machine would gently pull it into position. This was a durable system. But the NES didn’t have that—its slot required force to insert, and it was hidden inside a box, making repairs difficult when issues arose.

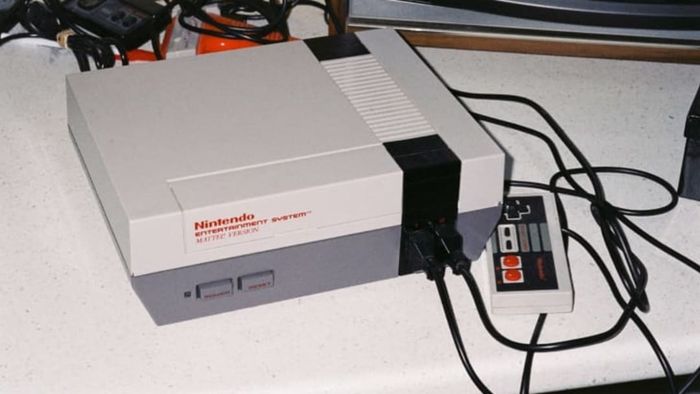

A variant of the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES. | Matthew Paul Argall, Flickr // CC by 2.0

A variant of the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES. | Matthew Paul Argall, Flickr // CC by 2.0In the NES, users opened a front flap, inserted a cartridge into the machine, and the insertion force took place at the back of the unit, where the (hidden) cartridge slot resided—pins inside the cartridge pressed up against the slot at the rear. Then the user would press the cartridge down (imitating the action of a VCR) and power up the console. This little routine felt incredibly satisfying, but over time, the cartridge slot became dirty, the springs lost their resilience, and the cartridges themselves accumulated grime. All these factors combined to create poor contact between the cartridge and the slot, resulting in the game failing to work—poor connections meant the machine couldn’t communicate with the cartridge, leading to frustration.

Metal vs Oxygen: The Ultimate Battle!

Nintendo designed the NES connector with nickel-plated pins bent into a shape that would slightly flex when a cartridge was inserted, then snap back once removed. However, these pins became less springy with frequent use, making it harder for them to grip the connectors of the game cartridge. To make matters worse, the cartridges themselves featured copper connectors. Copper tarnishes when exposed to air, developing a distinctive patina. Although this patina wasn't usually severe enough to cause issues, a particularly enthusiastic kid (like me) might notice it and decide to clean it—using everything from erasers to steel wool to various solvents (side note: my dad, a computer guy, had access to a magical substance called Cramolin—apparently, it was worth its weight in gold and could clean anything). Overzealous cleaning could end up damaging the connector, making the cartridge unplayable. I know this because I did it.

Blowing on the Cartridge

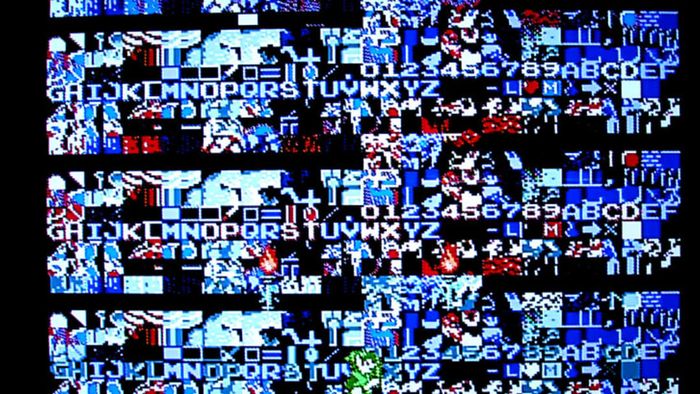

When things went wrong with your NES, the culprit was usually a bad connection between the cartridge and the slot. This could be caused by tarnishing, corrosion, dust, weak pins in the slot, or other issues. A poor connection could manifest as the game not starting, the console flashing a blinking light, or the game loading with random junk on the screen (below, a photo of Zelda II shows such a glitch). To solve these problems, in the mid-1980s, my friends and I somehow discovered a secret: if we removed the cartridge, blew on it, and then put it back in, it would work. And if it didn’t work the first time, it would usually work by the second, fifth, or tenth attempt. But looking back, I wondered: did blowing really make a difference? And if so, why? Was dust the issue, and I was just blowing it out of the cartridge? I spoke to several experts (who were quick to clarify they weren’t experts, despite their qualifications) to get to the bottom of it.

A glitch in Zelda II. | Kevin Simpson, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0

A glitch in Zelda II. | Kevin Simpson, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0More Nintendo Articles:

First, Vince Clemente, producer of Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters—a documentary about the iconic NES Tetris players. Clemente shared, "[Blowing in the cartridge] is actually terrible for the games and makes the contacts rust. You really shouldn’t do it. But it works. [laughs]" This encapsulates the issue: despite knowing that blowing on electronics wasn’t the best idea, we did it anyway. It seemed to work.

Next, I reached out to another expert, Frankie Viturello, a host on a gaming show and an experienced figure in various gaming projects—he also spent years working in a game store. Viturello’s first response was: "While I admit I may have engaged in a little cartridge-blowing as a naïve NES player, I’ve long since opposed it, believing that while it may offer temporary fixes, it ultimately leads to damage and stress on the hardware." So I dug deeper—in the mini-interview below, I’ve highlighted certain points.

Higgins: "How did the myth of blowing into cartridges spread across the U.S.?"

Viturello: "It was very much a collective experience, something all kids did, and many still do with modern cartridge-based systems. Before the NES, I don't recall people blowing into Atari or any other pre-NES cartridge-based systems (though that probably says more about the reliability of that hardware compared to the notorious front-loading 72-pin connectors of the Nintendo). I think a lot of it comes down to the placebo effect. The U.S. NES hardware required, on most games, optimal connection across up to 72 pins as well as communication with a security lock-out chip. The idea that 'dust' could be a real problem, and that 'blowing it out' would solve it, still sounds silly to me when I say it out loud."

Higgins: "Why would blowing into the cartridges have any effect? It feels like it works, sometimes."

Viturello: "While there are some collectors and enthusiasts who insist that the moisture from your breath won’t do any harm to an NES cartridge, from what I’ve observed over the last 20 years, I strongly disagree. I believe that there’s a solid connection between blowing into an NES cartridge and the potential for long-term issues like wear, corrosion on the metal contacts, and even mold or mildew growth."

"So, why does blowing into a cartridge seem to work? I’m no scientist and don’t have hard evidence, but I’m happy to offer some speculation. The most likely explanations, in my view, are: 1.) The act of removing, blowing into, and reinserting a cartridge probably gives the connection another chance to be properly made. So, removing the cartridge 10 times without blowing on it might yield the same results as blowing on it between every attempt. And 2.) The moisture from your breath could have an immediate effect on the electrical connection. Either it helps move debris or chemical buildup that develops when the contacts and pin readers rub together, or it increases conductivity enough to push through whatever was previously interfering with the connection. Those are my best theories."

Higgins: "What are some other methods you’ve heard of to get a stubborn cartridge working? I’ve heard of stacking a second cartridge on top of the one you're using, to force it down."

Viturello: "Methods like pressing down on the cartridge helped with the connection because the pin-connector setup was horizontal. By applying downward pressure, it pushed the cartridge pins more securely against the connectors, reducing the chance of a poor or incomplete connection."

The Study on Cartridge-Blowing

Viturello actually conducted an informal experiment on this very topic. He took two nearly identical copies of Gyromite, stripped off the plastic cartridge casing to expose the contacts (making them easier to photograph), and blew on one of them ten times a day for a month (all in one go, simulating the enthusiastic approach of a young gamer). The second cartridge was left untouched as a control. Both cartridges were stored in the same place, so in theory, this test should reveal any visual effects of repeated blowing—though it didn’t test the cartridges’ functionality in actual gameplay. The study does have a flaw: the cartridges weren’t exactly identical to start with (they appear to be slightly different revisions of the same board), so it’s possible that the contacts were coated differently between the two versions. Still, it’s the best data we have, and the results are pretty gross."

When you read the study, you’ll see the cartridges before and after the month-long test, and it’s pretty disgusting. The results are unclear—whether it’s copper patina, mold, or something else—but it’s obvious something happened. See also: One person’s reaction to the study where they describe an extreme case of N64 cartridge licking.

Nintendo Speaks Up

In a short message on its NES Game Pak Troubleshooting page, Nintendo says:

Do not blow into your Game Paks or consoles. The moisture from your breath can cause corrosion and contamination of the pin connectors.

So, the Conclusion is No

So, dear readers, all evidence points to a definitive no: blowing into the cartridge did not help. I believe the blowing was purely a placebo, giving users one more shot at a successful connection. The issues with Nintendo's connector system are well-known, and most of them were mechanical—simply wearing out faster than anticipated.

That being said, it's clear that kids can get pretty messy, and dirt getting into the cartridge or slot was a genuine issue—I doubt most of that dirt was just dust, though, and it probably needed more than just a quick puff of air to clean it out. In fact, Nintendo released an official NES Cleaning Kit in 1989 to help keep both the slot and cartridges clean. Ultimately, Nintendo revamped the NES console, launching the NES 2 in 1993, which became known as the "top loader." Its defining feature? A top-loading slot. This was more akin to the original Famicom, with a slot that stood up better to wear and tear. Likewise, the SNES (Super Nintendo Entertainment System) adopted a similar top-loader design.

Repairing Your Old NES & Keeping Your Games in Shape

If your NES is experiencing connector issues, it’s likely fixable, and you might even be able to do it yourself. Check out iFixit's repair guides for some common solutions, including one of the simpler fixes—replacing the springs that hold up the cartridge slot. While mine never broke, I had plenty of friends with malfunctioning springs. We can fix this!

When I asked Viturello about cleaning cartridges, here’s what he had to say:

Viturello: "The best ways to clean game cartridges are: using isopropyl alcohol and swabs, or more recently, I and others have found that non-conductive metal polish like Sheila Shine or Brasso works exceptionally well and also provides protection against some of the elements that would otherwise cause the natural tarnish that happens through regular exposure and normal use."