For students, summer is a break from the structured routine of school. For educators, it posed a growing challenge. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, many feared that kids were becoming so engrossed in television and summer fun that they were neglecting reading entirely. When school resumed, their reading skills had noticeably declined.

A group of educators and broadcasters came up with a unique solution: Launch a new program during the summer to use TV as a tool to spark children's interest in books.

This led to the creation of Reading Rainbow, a program that mixed magazine-style storytelling with readings of books, followed by thematic explorations in outdoor segments. Hosted by LeVar Burton, the show began as a modest trial on PBS affiliates like WNED Buffalo and Great Plains National in Nebraska. Over 150 episodes and 26 years, it became one of the longest-running children's shows on public television. If Sesame Street introduced kids to the alphabet, Reading Rainbow fostered a lifelong love of reading, words, and storytelling.

Despite Rainbow's noble intentions, the series faced frequent threats of cancellation due to financial constraints. Without popular characters or licensing deals that fueled success for shows like Barney, the producers struggled to persuade investors of its value. In 2006, as the media landscape and public television shifted, Rainbow aired its final episode. However, both the show's fans and Burton refused to lose hope.

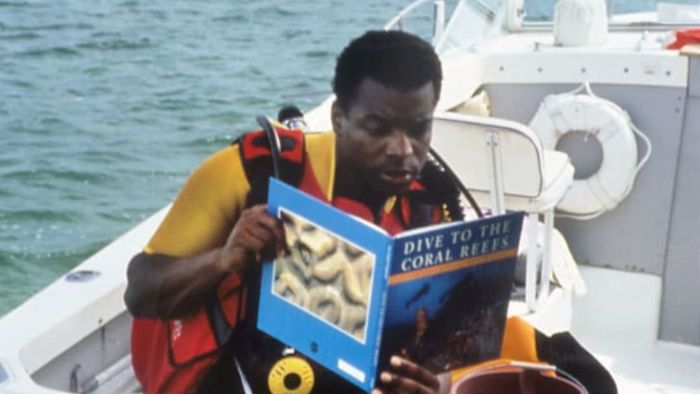

With the Reading Rainbow brand revived through apps and digital platforms, Mytour reached out to several members of the production team to reflect on its beginnings, the adaptation of the timeless activity of reading for the evolving medium of television, and how Burton didn’t let obstacles like elephant snot stop him from inspiring generations of children to embrace reading.

A moment from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZ

A moment from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZIn a 1984 study by the Book Industry Study Group, young adults under 21 showed a significant drop in their interest in reading. In 1978, 75 percent of them reported they read books, but by 1984, that number had fallen to 63 percent. In Buffalo, New York, and Lincoln, Nebraska, two public television employees became determined to figure out how television—once considered a distraction for children—could be harnessed to counteract this decline.

Twila Liggett (Co-Creator, Executive Producer): I had been hired by ETV in Nebraska, which was responsible for distributing educational programming to classrooms. One day, my boss approached me with an idea: 'We’d like to create our own television content, rather than just distribute it.' That’s when I started considering a project focused on reading.

Cecily Truett (Producer): Bringing books to television wasn’t a novel idea. Captain Kangaroo had already done it. It was Tony Buttino who introduced the concept of addressing the summer reading loss issue through television.

Tony Buttino (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Former Director of Educational Services, WNED): I began researching the summer reading loss phenomenon, which stemmed from studies in California. The central idea was: Kids stop reading during the summer. When they return to school in the fall, teachers need two to three weeks to help them regain their previous reading levels.

Pam Johnson (Former Vice President, Education and Outreach, WNED): The station consulted with educational advisors, and Tony kept hearing from professors, librarians, and teachers that there was a need for a program that could foster a love for reading during the summer. Providing this early foundation would set kids on the path to academic success.

Buttino: I began evaluating other summer programs available at the time. One was called Ride the Reading Rocket, which we aired for a few years starting in 1977. Although I wasn’t fond of the show, it was a start. We also provided workbooks to classrooms that wanted to use them.

Liggett: A lot of classroom materials were being produced at the time, but they weren’t exactly high quality.

Johnson: Tony took us back to the late 1950s and early 1960s, when WNED first started broadcasting live television. Back then, you might see a nun reading books or a zoo keeper talking about science. It was the beginning of that concept.

Buttino: After Rocket, I visited Fred Rogers. He introduced us to David Newell, who played Mr. McFeely on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and we filmed a series of short wraparounds with him over the following summers.

Johnson: WNED would experiment with existing programs. They all served as precursors to Reading Rainbow, helping to demonstrate why television could be a valuable tool for this kind of work. WNED acted like an incubator for these ideas.

Liggett: I wanted to create something that reflected what I did in the classroom—reading aloud to kids, getting them involved in the experience of reading, and encouraging them to talk to one another about what they were reading. These became the three foundational elements of Reading Rainbow.

Buttino: Prior to Reading Rainbow, we had The Television Library Club. It was effective, but eventually, we began wondering, "What kind of show could we create if we had the budget?"

Lynne Ganek (Writer): The initial goal was to develop a summer series for inner-city kids who couldn't attend camp, helping them stay engaged with reading. Larry, Cecily, and I sat down and thought, "This could be more exciting if we approached it from a different angle."

Buttino: I essentially drew from research done for The Electric Company, which found that if you can get second-graders to fall in love with reading, it marks a pivotal moment. Fifth grade might be too late for that.

Liggett: Nebraska's ETV and Great Plains ended up collaborating with WNED in Buffalo. Ride the Reading Rocket wasn’t meeting the need anymore, so I proposed we take my idea and tie it to the summer reading trend.

RRKIDZ

RRKIDZJohnson: After comparing their notes, it became clear that everyone was headed in the same direction. Though different individuals had their own interpretations of how it could play out, the consensus was strikingly similar.

Ellen Schecter (Writer): The challenge was clear: How do you keep children reading throughout the summer? Numerous studies showed a drastic drop in reading, but offered few solutions to address the issue.

Ganek: The goal was never to teach children how to read, but rather to cultivate a passion for reading.

Liggett: It was never about phonics, but about fostering a love for storytelling. It was the perfect transition for kids who had outgrown Sesame Street. You'd engage them with Sesame Street and then guide them to Reading Rainbow.

Truett: Tony was the one who identified the phenomenon, and it was Twila who suggested, 'Why not turn it into a TV show?'

Liggett: Tony often claims the idea was his, and I don’t mind that at all. Success has many creators, but failure stands alone.

Buttino: The term 'creation' is quite intriguing. I would say I created it, but then Cecily, Twila, and Larry came in and reimagined it. If I hadn’t spent five summers piecing together the core of the program, I’m not sure how it would have evolved.

Ed Wiseman (Producer): What stands out to me is how Ellen Schecter embodied the heart and spirit of the show. Larry and Cecily were the ones who coordinated everything and brought it together. Watching the dynamic between the three of them was incredible.

With Liggett and Buttino convinced that a show focused on reading was feasible, the execution was entrusted to Cecily Truett and Larry Lancit, a married couple who owned Lancit Media in New York City. Having produced the children's show Studio See and medical education programs, the couple knew how to blend imagination with informational television on a budget.

Truett: Tony introduced us to Twila and explained that the goal was to keep children engaged with reading. I thought to myself, 'How can we achieve that on television?'

Schecter: We would gather at Cecily and Larry’s apartment on West End Avenue and brainstorm about the type of show we wanted to create.

Wiseman: I remember getting a call to meet with this couple who produced from their apartment. I showed up in a three-piece suit, thinking that was the proper attire. They were so laid-back and easygoing.

Truett: I greeted Ed at the door while wearing a bathrobe.

Ganek: At the time, I was working at WNET in New York. Tony and Cecily hired me as an associate producer when I was nine months pregnant.

Liggett: Cecily and Larry were the masterminds behind the show's design. They have always been exceptional producers.

Ganek: Cecily had a way of letting everyone speak freely, while also giving honest feedback. I would pitch an idea and she'd tell me, 'Lynne, that idea is terrible.'

Schecter: One of our early concepts was to have people simply sitting around a library, but it felt too dull and lifeless. That idea was quickly dismissed.

Liggett: We briefly considered displaying the words on the screen for kids to follow along as they were read to. We looked at shows like Zoom, Sesame Street—the giant of children's TV—and Mister Rogers for inspiration.

Ganek: I grew up watching Mr. Rogers and later had the chance to know him personally. He always believed that children should be spoken to directly by the host, and he was a big fan of the show.

Truett: We had the opportunity to meet Fred, who became a wonderful mentor to us. Our aim was to form the same kind of connection with our audience that Fred had cultivated with his.

Liggett: The name came about because we knew children loved alliteration, and we wanted 'reading' to be a prominent part of the title.

Buttino: The name Reading Rainbow was actually suggested by an intern at WNED.

Ganek: The approach we established served as the foundation for the next 26 years of production, so I believe we did something right.

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting agreed to finance about half of the first season’s 15 episodes, leaving Liggett to approach corporate sponsors for the remaining $1.6 million needed.

Liggett: It took roughly 18 months. I became a bit unbearable to live with. People kept urging me to move on. My then-husband even remarked, “You care more about this project than you do about anything else,” as though he himself was the 'anything else.'

Ganek: Twila played a crucial role in securing Kellogg’s support.

Truett: Twila was a determined Nebraskan with unyielding resolve. Her strength was unmatched.

Liggett: I had written proposals for funding before, but nothing of this magnitude. My breakthrough came when I reached out to a contact at the University of Nebraska Foundation for help. Although he couldn’t get the funds from the school, he mentioned, “I sit on the Kellogg’s Foundation board. I’ll reach out to the CEO and tell him he should meet with you.”

Schecter: We were always pushing boundaries, asking things of people that most wouldn’t even consider approaching in their positions.

Liggett: I went to Kellogg's alone. Looking back, I'm not sure what gave me the courage. But I had enough of the show planned out to convince them it was a worthy idea.

Rev. Donald Marbury (Former Associate Director, Children’s and Cultural Programs, CPB): At CPB, we funded about half of the budget. That’s typical in public broadcasting. PBS can’t fully fund anything; we provide the initial funding to attract other grants.

Liggett: With support from both Kellogg’s and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, we had enough to fund 15 episodes. Without Kellogg’s, the show would have never launched.

Money wasn’t the only challenge for the production. Without an engaging host, Reading Rainbow risked being overshadowed by more thrilling programming.

Truett: [The original host was supposed to be] Jackie Torrance, a respected storyteller. But we also recognized that boys were at a higher risk of falling behind in reading, and we needed a strong role model. We considered about 25 candidates or so.

Buttino: I was looking for a host you'd trust enough to buy a used car from.

Lancit: We had been wondering—who was that guy who spoke at the Republican Convention? Scott Baio.

Buttino: I didn’t want someone robotic or someone in a ridiculous costume, like a sheepdog or something. I wanted someone genuine. I think I even mentioned Bill Cosby in the proposal.

Ganek: We attended a children’s TV conference and LeVar was there. He had just finished working on Roots at that time.

Truett: Lynne said, “Have you seen LeVar lately? He’s so charming, articulate, magnetic.” We thought, “Wow, this guy is the perfect fit.”

Schecter: Everyone recognized him as Kunta Kinte from Roots. He was so full of energy and expression.

LeVar Burton (Host): I had done two seasons of a PBS show called Rebop out of Pittsburgh. I had a strong attachment to PBS. It made perfect sense to me, especially after the impact of Roots. You could truly feel the power of television. Over eight nights, it showed the profound shift in understanding slavery in this country.

Lancit: I recall Lynne calling us and saying, “You really need to check out this guy. He’ll be on the six o’clock news.” We tuned in, and he just had this remarkable presence.

Liggett: Larry sent me a note saying I wouldn’t believe how camera-friendly he was. I saw him perform a poem on stage for Scholastic’s high school contest winners, and he was magnetic. You couldn’t take your eyes off him.

Ganek: We decided to reach out to LeVar, and he agreed to shoot the pilot.

Schecter: Once LeVar agreed, that was the final decision.

RRKIDZ

RRKIDZBurton: I loved the unconventional approach. It was no secret that kids spent plenty of time in front of the TV, so we thought, let’s meet them where they are and lead them back to the written word.

Ganek: At that time, LeVar was managed by Delores Robinson, who was married to Matt Robinson, the actor who portrayed Gordon on Sesame Street.

Liggett: She was an ex-English teacher.

Truett: Lynne reached out to her when LeVar was filming for ABC’s Wide World of Sports on the Zimbabwe River. She told her, “He’s not even in the country, but he’ll make it happen.”

Ganek: [Delores's] passion was in children's television, and she played a key role in persuading LeVar to take part.

Burton: I was fully committed. It just made perfect sense to me.

Truett: Back then, having an African-American host for a children’s TV show was completely groundbreaking.

Marbury: He was definitely the first African-American host, and beyond his race, he was the first true celebrity we secured for a public broadcasting series.

Burton: It wasn’t something I thought about at first, but as time went on, it became more apparent. I often like to point out what Bill Cosby, Morgan Freeman, Laurence Fishburne, and I share: we’ve all been involved in children’s television.

Schecter: I would review scripts with him, asking for his thoughts. He really infused his own experiences into the show, like when he shared how learning to ride a bike felt terrifying until he realized his father wasn’t holding on anymore. It was a perfect story for kids, and it felt authentic because it truly was.

Wiseman: I’d say that on the show, LeVar was about 70 percent himself and 30 percent tailored for the audience. He was playing himself, but also a version of himself, if that makes sense.

Liggett: The influence of LeVar was extraordinary.

Truett: No young black men had ever taken charge of a show like this. He was similar to Fred Rogers, speaking directly to the audience.

Rainbow’s format of focusing on a single book had very little precedence. Out of 600 potential choices for the first season, 67 were selected. While producers thought publishers would appreciate the free publicity, not all of them fully understood the aim.

Ganek: I’d visit the library, start pulling books off the shelves, sit down on the floor, and read them.

Schecter: The goal was to select a book that had enough substance to base a whole show on. If the story was about dinosaurs, we’d go dig for fossils at Dinosaur National Park. If it was a camping book, we’d go camping. We filmed a volcano eruption—anything thrilling to capture kids’ attention. The book needed to leap off the page and feel alive within the show’s context.

Ganek: We were looking for something either whimsical or serious.

Schecter: When we selected the books, we contacted the National Library Association to ensure that the titles we showcased would be available when children went searching for them. If you’re introducing a child to a book, they need to be able to find it.

Ganek: During the first season, we had to pay for the rights to use the books. Nobody was going to let us use them for free. It wasn’t a large amount, but we still had to make the payment.

Liggett: It was a tough situation. That’s why we mainly used lesser-known authors in the first season.

Schecter: I think there was some concern about how the books would be presented.

Truett: We approached Macmillan and explained that we were creating a series about summer reading loss and had no budget, so we asked if we could have the books for free. The person we spoke to was shocked and replied, 'I don’t see how this will sell any books for Macmillan.'

Liggett: They just couldn’t fathom how we could stretch the story over a full half-hour episode.

Truett: I believe we spent a few hundred dollars on the first book.

Schecter: Once publishers realized they’d be featured on TV, it would have been pretty foolish for them not to agree.

Liggett: We had to work out deals with both the author and the illustrator, as many of the books were picture books.

After a book was selected, it was Lancit Media's job to figure out how to film its pages in a visually captivating way.

Ganek: Preserving the artwork’s integrity in the books was incredibly important.

Liggett: I like to joke that we were the Ken Burns of our time. We would move the camera across an illustration just as a child’s eye would, from left to right. That was all Cecily’s idea.

Truett: Before this, I had worked with Weston Woods, a company that turned books into slideshows. The kids could actually see the illustrations, rather than having the teacher hold up a book for everyone to peer at. We knew we had to keep things dynamic.

Lancit: We quickly realized that cel animation was beyond our budget. Instead, we adapted the books in a way we called iconographic. We moved the camera across still images. We’d get copies of the books from publishers, cut out the pages, and send them to a company in Kansas to adapt them, extending characters or adding extra art if something got cut off. Later on, we would add limited animation if it made sense.

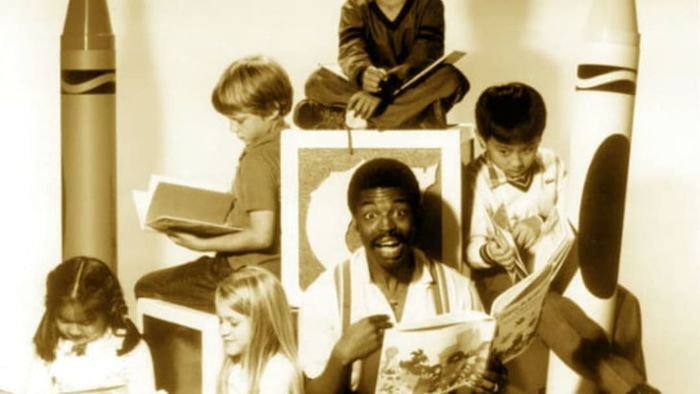

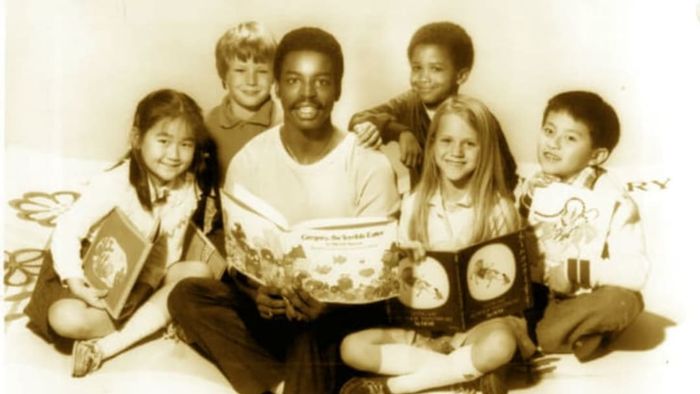

A clip from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZ

A clip from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZReading Rainbow was structured into three parts: a book reading, a related field trip, and a final segment where kids discussed other similar books. It gave children on television a rare chance to express their opinions.

Schecter: A big deal was having children review the books. It wasn’t common for kids to talk about books on TV.

Buttino: We found the kids from Buffalo for the first few years.

Johnson: These were actual kids from real neighborhoods in Buffalo. We would audition hundreds of them and ask, “Which one of these 6-year-olds has that presence?”

Ganek: I have to give credit to a librarian from New Jersey. She was the one who came up with the idea for kids to do book reviews. She kept a small file on her desk filled with reviews from kids and said, “Here, you don’t have to just take my word for it.” That’s where LeVar’s famous line came from.

Schecter: I remember writing that line myself. It was my idea to have kids review the books. The main book would be featured, followed by something like, “If you enjoyed this, you’ll also love these.”

Truett: That was Ellen Schecter, no doubt about it. We included it in one of the scripts, and we thought it would be a great way to wrap up each show.

Ganek: We discovered a little girl who was amazing at doing reviews, and we planned to feature her throughout the series. In the end, we decided to have a different kid every time.

Truett: Our research revealed that kids loved watching other kids review the books.

Ganek: We were later accused of coaching the kids, and while some of that was true, it was mostly their own words.

With the funding secured and plans set, filming for the pilot episode kicked off in early 1983.

Liggett: Initially, Kellogg’s agreed to fund us but insisted on seeing a pilot episode first, which made sense. However, one of their assistants pulled me aside and reassured me, saying, “Don’t worry. We love the show. Just go ahead and make it.”

Truett: LeVar arrived in New York City to shoot, having just flown in from Africa on the red-eye. It was 7 a.m. and he asked if he could have a toothbrush and a glass of orange juice.

Burton: I didn’t have any time to prepare. Speaking directly into the camera and breaking the fourth wall is not something actors usually do. I had to quickly adapt and learn to speak as if I was talking to just one child.

Wiseman: He was so genuinely sincere. I recall filming that moment, and he was crafting his character through the smallest details. He had a backpack, and it was like, “Should he carry it? Should it be slung over his shoulder?”

Burton: I initially thought they were just looking for me. Over time, I really honed in on the voice of LeVar on Reading Rainbow, and I realized it was the part of me that either was a 10-year-old or could relate to them. It was like they were one and the same.

Schecter: We did allocate some funds for animation, like the scene where a woman opens a book and this massive cloud of activity pours out of it.

Liggett: We reached out to the team that had just completed an animated Levi’s commercial. Our goal was to have real kids transform into animated ones. We nearly exhausted our budget just doing that.

Truett: There was one segment we took out of the pilot because it didn’t work. It was called “I Used to Think But Now I Know,” and it focused on how first impressions aren’t always accurate. It ended up being a dud.

Lancit: When we had to remove that segment, we needed to fill in the gap. We ended up filming a tortoise in Arizona slowly making its way across the ground. I approached our music guy and asked, “Can you come up with a song for the tortoise?” I had no idea what he’d come up with. The result was a charming little tune, just two minutes of this slow-moving tortoise.

Ganek: After the pilot, I had one interesting experience. I visited Dorothy and Jerome Singer, two professors from Yale who had worked in children's television and had a column in TV Guide. I admired them greatly, so I brought the Reading Rainbow pilot for them to review. They later wrote me back saying it was terrible and would never go anywhere. So much for academia.

A scene from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZ

A scene from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZReading Rainbow debuted on July 11, 1983, as the first summer program funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Though it wasn’t the first episode to air, the pilot, which featured the book Gila Monsters Meet You at the Airport, served as a memorable introduction to the series for the team behind it.

Ganek: Someone at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting feared it might be too frightening.

Wiseman: The word “monster” in the title sparked a lot of debate.

Schecter: Often, individuals with a high opinion of themselves make assumptions about what children will or won’t enjoy. In reality, the book wasn’t scary at all.

Truett: One of our advisors had a traumatic childhood memory of a Gila monster being brought to her home. It stayed in a cage next to her while she slept.

Liggett: We were fully committed to the idea and pursued it with great determination.

Truett: Gila Monsters was an ideal choice as it demonstrated how we could connect a book to a child's real-life experiences, like the fear of moving.

Ganek: I was part of the pilot even while I was pregnant, and I remember PBS being uncomfortable with having a pregnant woman on screen, so they filmed me from the neck up.

Truett: The reaction was overwhelmingly positive. We featured actual Gila monsters on the show, and the audience loved it.

Schecter: The public’s response was incredibly favorable. It wasn’t like Sesame Street—older children were tuning in and enjoying it as well.

Wiseman: It became the most popular children's show among adults. They’d watch it even when their kids weren’t around.

Liggett: There were times when we were told to speed things up, but we trusted that a child’s attention span would allow us the time to take things at the right pace.

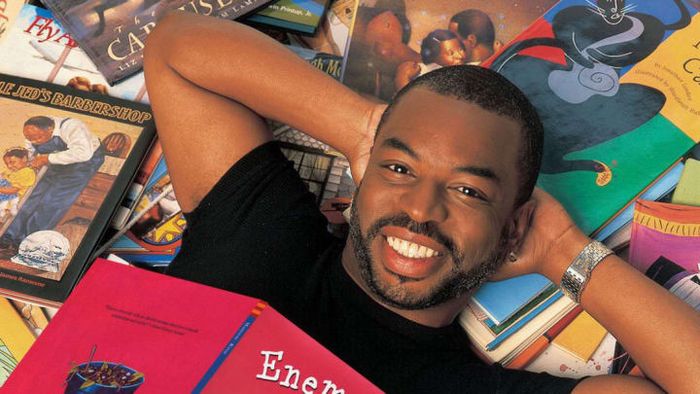

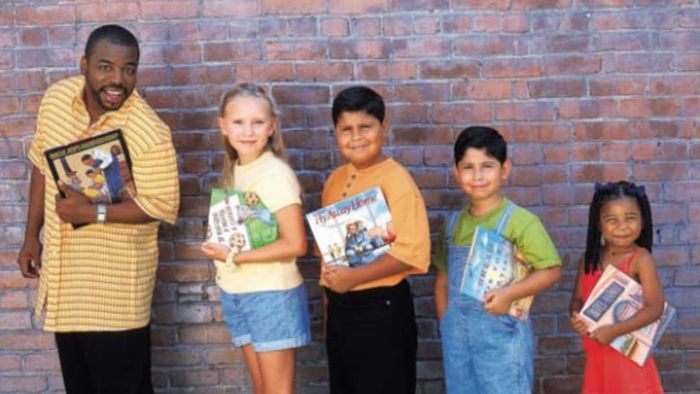

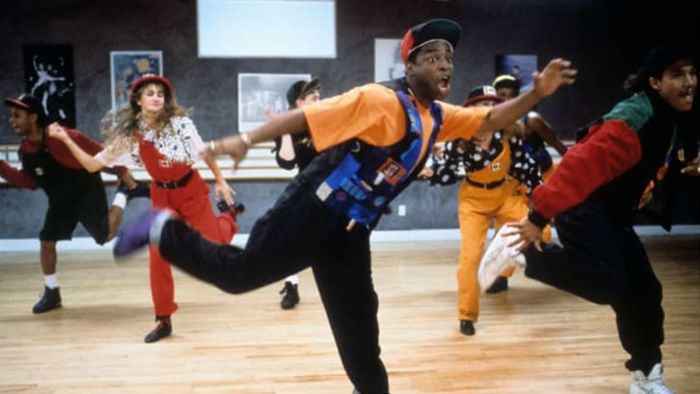

LeVar Burton | RRKIDZ

LeVar Burton | RRKIDZThe discussions weren’t always about the books. As time went on, Burton’s hairstyle choices and facial grooming became popular topics of off-camera conversation.

Truett: One thing we had to constantly adjust to was deciding on LeVar’s hairstyle for each year... There were also frequent discussions about his mustache.

Burton: And then there was the time I got my ear pierced.

Marbury: We had some great discussions about his choice of haircuts.

Burton: I recall those conversations and I distinctly remember saying, “If you want me, you’ve got to accept all of me.” Whether it was my mustache or my earring, my sincerity and passion were what mattered.

Wiseman: His hair and overall style would evolve every year depending on his acting roles. He had a thing for a mustache, but the concern was that it made him seem older, like a father figure instead of a peer.

Truett: The producer called and said, “Tell him to lose that thing.” They wanted more consistency since he didn’t have it in the first season. He shaved it off, though he wasn’t too thrilled about it.

As Reading Rainbow gained momentum, publishers and authors began to realize its impact on their sales. Some books saw such an increase in demand that they went back for reprints or released paperback editions to keep up.

Burton: The running joke was that we’d wear kneepads because we were begging publishers to let us showcase their books on TV. In the 1980s, TV was still seen as a villain in academic circles, viewed as a rival to reading.

Ganek: By the end of the first season, we could hardly find space in our office for all the books we were receiving. Publishers would send us just about everything they had.

Wiseman: We received boxes every single day.

Schecter: The entire children’s book industry exploded. Some books saw a massive increase in sales, with some going up by as much as 800 percent.

Liggett: Children would walk into libraries asking for the books they had seen on the show.

Truett: Publishers began producing small Reading Rainbow stickers to affix to the featured books.

Ganek: The show revolutionized how children's books were published. Prior to Reading Rainbow, print runs were small, but after the show, the numbers grew substantially.

Truett: They finally understood the impact when they saw the show. Reading Rainbow directly contributed to the sale of thousands of books.

Schecter: Once they recognized how thoughtfully we treated the work and how we enlisted stars like Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep to narrate the stories, they got it.

Ganek: We had no funding, so anyone you heard narrating the stories did so because they believed in the value it would bring to children.

Liggett: Some chose to donate their payment to charity, while others did it completely for free.

In the second season, Rainbow’s episode count would be reduced to just five episodes. Constrained by a tight budget, it became one of many public television projects struggling to secure funding. As PBS programming head Suzanne Weil remarked at the time, “It’s a very scary time for children’s television.”

Liggett: We never did 15 episodes in a season again; it became too challenging to raise the necessary funds.

Schecter: Finances were always a concern. We’d manage to secure funds, but often not in time to keep a consistent flow of episodes. The real issue was the need for a reliable schedule to keep production and broadcasting on track.

Lancit: It's rare for a series to receive consistent funding with no risks involved. There were times we were just weeks away from putting everyone on a break, then somehow the funds would come through and we’d be back on track.

Ganek: Twila was the driving force behind securing the funding to keep the show going.

Truett: Every time we were on the verge of letting everyone go and calling it quits, Twila would pull off a miracle. She’d shake things up and find the money we needed.

Liggett: There was never any certainty. One year, I thought we had the budget for the season, then my contact at Kellogg's went on vacation. The funds got redirected, and when she returned, I was told the money was gone.

Schecter: Companies like Kellogg’s and CPB didn’t fully grasp the need to keep the production moving. There would be a delay of a month or two, and then we’d be scrambling to catch up.

Marbury: We made sure to fund it every single year. It became a cornerstone for us—a flagship children’s series that we fully supported.

Liggett: At one point, Barnes & Noble was the source of our funding.

Schecter: The constant questions were: How much will they give us? And how much can we realistically afford to spend?

Liggett: A friend of mine recommended the National Science Foundation. Since we focused on science-themed books, it made sense. But after a while, it became clear: 'You've had your run here. We can't keep funding this show indefinitely.'

In contrast to Sesame Street’s extensive cast of easily marketable characters, Reading Rainbow didn’t lend itself to many licensing opportunities, which is one way shows can secure financial backing.

Liggett: We left no opportunity unexplored to secure licensing deals. A friend arranged a meeting with Joan Ganz Cooney, the head of Children’s Television Workshop. She told me, 'Let me be clear: You won’t make much from selling book bags.'

Truett: We didn’t have those huggable characters that kids could snuggle with at night.

Wiseman: What made us unique was the lack of gimmicks, but that also made us harder to market. We didn’t have the kind of licensing revenue coming back to fund the show.

Liggett: There was a time when I wasn’t far from Hallmark in Kansas City. I visited, thinking 'Surely, Hallmark would be interested in something like this.' Their licensing manager basically told me, 'The issue is, you have these books, but you don’t actually own them.'

Truett: Publishers were the biggest winners from the show. We even discussed the possibility of adding a character to the show that we could license. We thought about the butterfly from the opening sequence, but it seemed too cheesy.

Burton: I was extremely hesitant about that concept. Fortunately, we never followed through with it. I believed that introducing another major character out of nowhere would negatively affect the connection I had with the audience.

Wiseman: I recall a college professor once discussing children's television and mentioning that animation and puppetry were losing their emotional depth. LeVar was so genuine. It felt like going back to the Fred Rogers approach.

Johnson: We never had LeVar dolls, nor did we find ways to capitalize on those additional rights.

Liggett: We never managed to figure it out.

A scene from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZ

A scene from Reading Rainbow. | RRKIDZDespite facing budget limitations, there was always a portion allocated for location shoots. Some of the most iconic segments took us to a zoo, a Chinatown parade, a live birth, and a maximum-security prison.

Ganek: Once we picked a book, we gathered around in a circle and brainstormed what we could do with it. This led to field trips based on what we could afford. We visited some fascinating places, including a whitewater rafting trip in Arizona. While we didn’t have funds to pay experts, people were always eager to donate their time when it was for children’s programming.

Schecter: LeVar was an amazing sport. During the camping episode, it rained non-stop.

Liggett: When he landed Star Trek [in 1986], he would shoot there for a week and then come back to our show on the weekends. Incredible stamina.

Burton: I genuinely thought my time with Reading Rainbow was over when I joined Star Trek: The Next Generation. I felt I'd given it my all, and it was time to move on. They even started looking for a new host. But then Rick Berman, the executive producer of Trek, told me he had a background in children’s programming and a special fondness for it. He ensured I could still shoot Rainbow whenever I needed to.

Schecter: I recall LeVar filming at a zoo, and one of the elephants had a cold, constantly sneezing and covering him in snot. He stayed calm, though. “Alright, let’s try that again.”

Truett: That was hilarious. The elephant was reaching for the apples LeVar had, and this stream of snot just shot out of its trunk.

Burton: My goal was always to maintain a natural conversation with the viewer. It can be hard to do that when you've got elephant snot on you. Meanwhile, I had goats trying to chew on my clothes.

Truett: We had to rescue him from a goat pen before he got trampled.

Wiseman: I recall filming near an active volcano. We left our editor about a mile away from the eruption site.

Liggett: We once shot an episode on the Starship bridge. Patrick Stewart is, without a doubt, one of the most polite individuals I've ever encountered.

Truett: The biggest mistake Trek made was covering up [LeVar's] eyes with that gadget. While viewers recognized him from Trek, on our show, he was speaking directly to the audience.

Ganek: The main, and really only, disagreements we had were about where to shoot. Someone would ask, “Where’s the best place for a dinosaur exhibit?” One person thought Pittsburgh, but another disagreed.

Schecter: Chinatown [in Manhattan] posed challenges. We filmed Liang and the Magic Paintbrush there, but it wasn’t easy. There are gangs, and you need to make sure you're on their good side. Somehow, we managed to win them over.

Truett: Over time, we began exploring more serious subjects. We covered the Underground Railroad, the issue of slavery, and even did an episode on Badger’s Parting Gifts, which dealt with grief and losing someone you love.

Wiseman: We filmed inside Sing-Sing, in areas that had never previously allowed cameras. We took subtle risks. We even captured the live birth of a baby! We worked closely with an OB/GYN and a mother to make it happen. It was a first for children’s television.

Lancit: We worked alongside a doctor to ensure no graphic images were shown. Everything filmed was above the waist.

Wiseman: Every PBS station aired it except for one: WNET in New York, of all places.

As Rainbow progressed, it garnered significant attention from libraries, publishers, and the television industry, earning a total of 26 Emmys for its outstanding contributions to children’s programming.

Wiseman: At the Daytime Emmys, people would give us curious looks. “Here come the Reading Rainbow folks.” I think we managed to win nearly every category.

Buttino: It was always a delight to get dressed up and attend those award shows.

Wiseman: During the 2003 Emmys, LeVar took the stage to accept the award and said, “This might be the last time we’re up here. There’s no funding.” And miraculously, we secured the funding right after he said that on TV.

Burton: I don’t recall that moment, but it sounds like something I would have said. Year after year, we kept going, even with the constant struggle for funding. I think Reading Rainbow always had some sort of unseen force looking out for us.

Lancit: I used to say we had Reading Rainbow karma. Whatever we needed, we always ended up getting it. People were always eager to lend a hand.

LeVar Burton | RRKIDZ

LeVar Burton | RRKIDZIn 2006, Reading Rainbow found itself in a difficult situation. The cause: the No Child Left Behind Act, which imposed restrictions on how the Corporation for Public Broadcasting could distribute funding.

Wiseman: We always believed more money would come through somehow, that Twila would find a way. We just couldn’t imagine the show ending—it was too important to let go of.

Liggett: We exhausted our funds in 2006 and aired our final episode that same year.

Truett: A part of it was the slow transition to other shows. Parents might have wanted their kids watching PBS, but when they left the room, the kids would go right back to Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers.

Liggett: To this day, I’m still puzzled by the funding problems we faced. Everyone claims to support reading and literacy—until you start asking for money.

Ganek: In some ways, our downfall came from encouraging children to embrace reading. The No Child Left Behind initiative was more focused on teaching the technicalities of reading.

Burton: The death sentence came with No Child Left Behind. The funding was strictly allocated for the basics of reading, with no room for fostering a passion for it. All the resources we relied on were no longer available to us.

Liggett: The technicalities of it all were frustrating, but basically, CPB received ready-to-learn funds, and then shows would fight for their share. I argued. I can’t even begin to tell you how hard I argued.

Marbury: There was increasing pressure from Congress to explore new directions. We had to start rethinking how much we were investing in the series year after year.

Truett: PBS had to make a case for its relevance to political groups. A lot of public television programming shifted towards animation, like Blue’s Clues.

Burton: We filmed our final episode in 2006, but it wasn’t until 2009 that we were officially removed from the lineup. After three seasons without new content, we were essentially canceled.

Even though the show continued to air reruns until 2009, Burton was determined not to let Rainbow fade into obscurity. In 2012, he and his business partner Mark Wolfe launched an iPad app, embracing interactivity and the evolving digital entertainment landscape. By 2014, their Kickstarter campaign raised over $6 million, setting a new record as the most-funded project in the site’s history.

Burton: When the show was taken off the air, it was a moment of realization for me. “Hold on, there’s something I can do.” In 2010 and 2011, we spent time securing the rights that had been scattered and worked to negotiate a deal with WNED.

Wiseman: Back then, it was the largest Kickstarter campaign ever, raising $6 million. That really demonstrates the incredible impact this show had.

Burton: It set the record for the most backers. It was truly overwhelming to witness the intense passion and support for the brand.

Schecter: I found it a bit surprising. LeVar owns Reading Rainbow? How is that even possible?

Burton: There was a chance to secure seed funding and assemble a team.

Liggett: From what I understand, WNED struck a deal with the University of Nebraska, and LeVar and his company made a broad licensing arrangement with WNED, but WNED still holds ownership.

Truett: I’m so happy that LeVar is continuing the Reading Rainbow legacy.

Buttino: I'm not sure if things are going smoothly between LeVar and WNED right now. I think WNED sold him some assets, and they're not too pleased about it. [WNED and RRKidz are currently involved in litigation over the Reading Rainbow license, with WNED accusing RRKidz of “illegally and methodically” attempting to “take over” the brand by pursuing projects beyond their original agreement.]

Burton: There's not much I can say about it at the moment. I’m hopeful and confident we’ll resolve it soon.

RRKIDZ

RRKIDZToday, Reading Rainbow stands as a landmark children's television show, its influence on both audiences and its creators immeasurable. Burton's RRKidz continues to impact young audiences through apps and various online versions of the series.

Ganek: The cast and crew of Reading Rainbow shared a deep bond of affection for each other.

Wiseman: If someone on the crew ever said, “It’s just a kids' show, it doesn’t matter,” they wouldn’t last long. It was precisely because it was a children’s program that we demanded it be the best.

Truett: We began as kids ourselves, and over the span of 26 years, we grew together.

Wiseman: I married Orly [Berger, a fellow producer]. Our children eventually appeared on the show too.

Liggett: We inspired children to read, and that made a profound difference. It’s like learning to play the piano—practice makes perfect.

Truett: It was one of the pioneering shows to spotlight books and literacy, showing the joy of reading and sharing that experience with your kids.

Johnson: PBS commissioned surveys, and over 18 years, teachers consistently reported that Reading Rainbow was the most-used video in their classrooms. They viewed it as more than just a reading show—it opened up worlds for disadvantaged kids, showing them things they may never have encountered, like a bee farm or a live volcano.

Wiseman: People talk about the show with such emotion, often with tears in their eyes.

Marbury: I’d place it right up there with Sesame Street. I truly would, in terms of emphasizing the importance of reading for our young generation.

Burton: A key element of Reading Rainbow was connecting literature to real-life experiences. I’ve lost count of how many people have told me that the show inspired them to pursue careers as writers, librarians, or even beekeepers. It profoundly impacted their lives.

Ganek: Today, so many people create their own versions of the Reading Rainbow theme song on YouTube. I even saw Jimmy Fallon, dressed as Jim Morrison from The Doors, perform it on his show with The Roots.

Liggett: People often sing the theme song to me.

Marbury: I could sing it for you right now! Butterfly high in the sky, I can go twice as high …

Buttino: Friends will mention my involvement with Reading Rainbow when we’re out at restaurants. Waiters even come up to me, showing me that the theme song is their ringtone. It happens all the time.

Lancit: I believe there was an authenticity in the way we presented the program that connected with kids and resonated with them in a way that never felt condescending. We spoke to them in a way that instilled confidence. Knowing I played a part in giving an entire generation of children that feeling is truly rewarding.

Truett: I firmly believe that the bond LeVar built with young viewers was crucial in helping them embrace a relationship with an African-American man. It shifted the perspective of a whole generation.

Wiseman: LeVar made color both significant and irrelevant at the same time. He transcended race, gender, and age.

Burton: There’s something deeply emotional about that golden moment of childhood, and Reading Rainbow taps into that for so many. It represented a simpler time in their lives. Things move much faster now.

Marbury: I don’t think enough children’s television has followed the example set by Reading Rainbow. Reading is the cornerstone of education, and we must continue to prioritize it in the educational system.

Schecter: Occasionally, I meet friends of my kids who tell me, 'You wrote Reading Rainbow? That was my all-time favorite show. I’d grab a book, close my bedroom door, and let my imagination soar.' That’s exactly what we aimed for.

Burton: It had a very serene, natural quality to it. We gave the audience space to truly connect with the conversation. I believe that’s what made it so special. It felt like they had a friend, someone who was cheering for them, who truly understood and cared. And that was genuine.

All images courtesy of RRKidz unless otherwise credited.