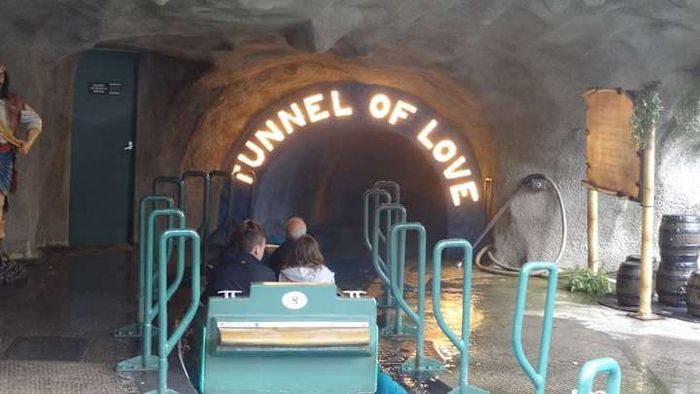

In TV shows, when two characters are on the verge of romance, they often end up at an amusement park. There, they encounter the Tunnel of Love—a cozy boat ride where couples sit close together, gliding through a dimly lit passage. This classic scene unfolds predictably: the nervous pair climbs into a two-person swan-shaped boat, their faces flushed. As they pass by glowing hearts and paper cupids, their hands subtly move closer in the shadows. By the time they exit the tunnel, their connection has visibly deepened.

For generations, the Tunnel of Love has been a recurring theme in television. Baby Boomers remember it from Scooby-Doo, Gen Xers from The Simpsons, and Millennials from Rugrats. Even today’s younger audiences recognize it from shows like The Loud House and Gravity Falls. Despite its frequent appearances in media, few people under 70 have ever encountered a real-life version of this iconic ride.

It’s easy to assume the Tunnel of Love is a fictional creation, akin to flying cars or human-sized air vents. However, this attraction was a genuine phenomenon a century ago. It gained immense popularity in the early 1900s, serving as a romantic haven for couples before vanishing almost as quickly as it appeared.

In the Mood for Love

At the dawn of the 20th century, Americans with extra cash were excited to explore a novel entertainment option: the amusement park. Unlike traveling carnivals or world fairs, these parks were permanent fixtures, emerging during the Gilded Age and flourishing in the early 1900s. Advances in ride technology sparked a golden age of amusement parks. (Rides back then were far less regulated than today, resulting in some dangerously flawed designs that, fortunately, have not been recreated.) Between descending into a dark ride to hell and blacking out on a looping roller coaster, visitors could enjoy a more serene—and romantic—experience in the Tunnel of Love.

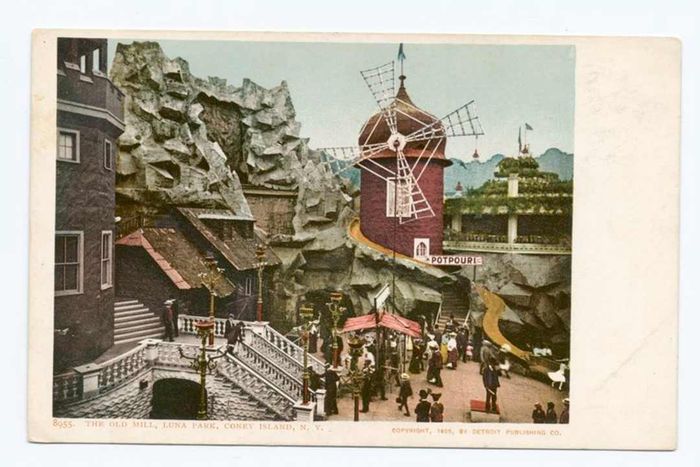

The Old Mill at Coney Island's Luna Park, circa 1898. | NYPL via via Wikimedia Commons

The Old Mill at Coney Island's Luna Park, circa 1898. | NYPL via via Wikimedia CommonsAs reported by Hopes&Fears, the ride first appeared as the Canals of Venice in London but gained immense popularity in the amusement park-crazy United States. The concept was simple: passengers boarded a small boat and drifted through dark, themed tunnels. Early versions of the ride were not romantic; in America, it was often called the Old Mill. Instead of love-themed decor, riders might have seen fake rocks and stalactites or murals of mythical creatures like leprechauns and gnomes.

Even without overtly romantic themes, many passengers didn’t hesitate to snuggle up to their companions. The Old Mill rides became popular during an era when unchaperoned dates among young people were considered daring. Couples, unless married, had limited opportunities for private moments. A slow, dimly lit ride offered one of the few socially acceptable settings for men and women to be alone and share physical closeness. The tunnel’s decor was irrelevant—what happened inside the boat was often far more thrilling than the surroundings.

A Useful Purpose

As reported in a 1950 issue of The Daily News, a journey through the Tunnel of Love typically lasted around 6 minutes—and many riders maximized every second. Paul Huedepohl, then-secretary of the National Association of Amusement Parks, Pools, and Beaches, famously remarked that “more romances begin in these tunnels than syllables spoken during a Congressional filibuster.”

Some passengers tried to extend their ride by clinging to the tunnel walls, halting the boat’s progress. When this caused the small vessel to tip over, soaked and laughing couples would have to exit on foot, often denying any involvement in the mishap.

Ye Old Mill ride at the Minnesota State Fair, circa 2005. | BenFrankse via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

Ye Old Mill ride at the Minnesota State Fair, circa 2005. | BenFrankse via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0The true purpose of the Old Mill for unmarried couples soon became widely known, prompting amusement park operators to lean into its romantic allure. Palisades Park in New Jersey pioneered the trend by renaming its boat ride the Tunnel of Love, inspiring parks nationwide to do the same. Some venues took a subtler approach, acknowledging the ride’s implicit function. If the Old Mill’s interior didn’t resemble a cave, love nest, or gnome’s dwelling, it often took on the appearance of a haunted house. Designers embraced the eerie ambiance, decorating tunnels with rubber spiders and fabric ghosts. As The Daily News wryly noted, leftover Halloween decorations often proved more romantic than traditional pink-and-red themes.

“Studies have revealed that the eerie sounds and grotesque sights along the ride, though obviously fake, often cause women to cling to their male companions,” the 1950 article stated. “Her fear is typically as artificial as the ride’s hazards, but it serves a practical purpose.”

Not all park operators were amused by the idea of premarital intimacy on their rides, and some took measures to curb it. Certain parks stationed guards on catwalks above the waterways to monitor and deter inappropriate behavior. Those who only received a stern look were fortunate. Kennywood Park in Pennsylvania allegedly armed its Old Mill staff with plastic bats, instructing them to strike any exposed buttocks spotted in the boats. Historical photos indicate this enforcement tactic wasn’t unique to a single attraction.

Jumping Ship

In 1950, approximately 700 Tunnels of Love were operating across the U.S., but over the next few decades, nearly all disappeared. Today, only a handful remain. Surprisingly, it wasn’t vigilant guards or concerned parents that led to the ride’s downfall—it was the sexual revolution.

As societal attitudes toward dating and intimacy shifted, unmarried couples no longer needed clandestine ways to be alone. They could freely go out without chaperones or even stay in together. While a traditional date lacked the excitement of cramming a relationship’s worth of passion into a six-minute ride, it was far more practical.

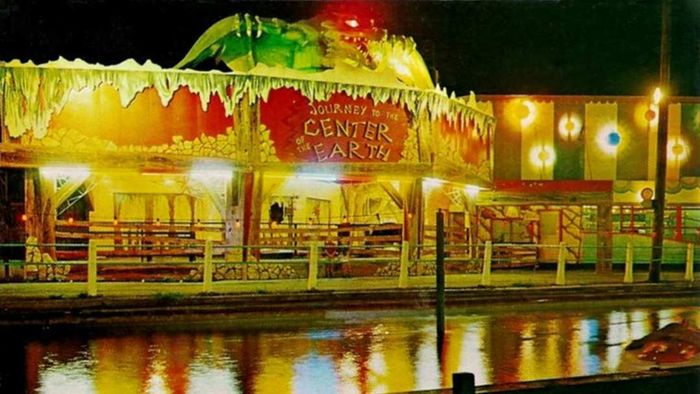

Journey to the Center of the Earth ride at Dorney Park, circa 1964. | Wikimedia Commons

Journey to the Center of the Earth ride at Dorney Park, circa 1964. | Wikimedia CommonsAs America’s views on sexuality changed, so did its preferences for amusement park rides. While adults were less inclined to engage in mischief on attractions, they still sought thrilling experiences. In the 1960s, parks shifted focus from slow, outdated rides like the Old Mill to adrenaline-pumping roller coasters. Some parks attempted to modernize their tunnel rides instead of removing them. Dorney Park in Pennsylvania added mechanical monsters to its Mill Chute, renaming it Journey to the Center of the Earth. Kennywood collaborated with cartoonist Jim Davis to revamp its Old Mill into a 3D black-light attraction called Garfield’s Nightmare. (For more on the ride’s history, check out this video from Defunctland.)

These updated versions of the ride were short-lived, and the handful of tunnel boat rides still in operation today remain faithful to their early 20th-century origins. While most contemporary amusement park visitors have never experienced a Tunnel of Love firsthand, they may not fully grasp what initially made these rides so iconic. However, the attraction’s influence endures. Its significant role in American culture continues to resonate, leaving a lasting imprint on songs, films, and TV shows. Unknowingly, modern couples pay homage to the Tunnel of Love’s legacy whenever they cozy up on a dark ride—even if they no longer feel the need to conceal their affection.