The iconic image of Jennifer Grey in her flowing pink dress, lifted high by Patrick Swayze’s character, is what most people envision when they recall Dirty Dancing or hear the opening notes of "(I've Had) The Time of My Life."

Since its 1987 debut, Dirty Dancing has captivated audiences, securing its status as a cultural classic and a staple of cable television. Yet, many fans may not realize the film’s deep connection to Jewish culture, a theme subtly woven into its narrative.

Kellerman's, the fictional resort in the movie, draws inspiration from the real-life Borscht Belt resorts in upstate New York, which catered to Jewish vacationers throughout the 1900s. The term 'Borscht Belt' was popularized by Variety journalist Abel Green, referencing the Eastern European soup commonly served at these establishments.

To appeal to a wider audience, explicit mentions of the Jewish identity of resorts like Kellerman's were largely omitted from the film. However, Dirty Dancing, penned by Eleanor Bergstein, a frequent resort visitor, accurately captured the essence of the Borscht Belt. Subtle references to this unique resort culture are scattered throughout the movie, though they may go unnoticed by casual viewers.

Before the rise of grand resorts like those that inspired Kellerman's, Jewish families in the early 20th century established modest boarding houses in the Catskill Mountains. These kucheleins offered affordable retreats for New Yorkers escaping the city heat, featuring communal kitchens and fresh milk from local dairy farms—a detail that would later play a role in the story.

As Jewish families grew wealthier and these boarding houses flourished, many evolved into luxurious resorts. These destinations became hotspots for socializing and entertainment. Iconic establishments like Grossinger's, Kutsher's, and the Concord hosted celebrities such as Eleanor Roosevelt, Judy Garland, and Milton Berle. Grossinger's even witnessed the marriage of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher in 1955. Meanwhile, Kutsher's Country Club became a stage for comedians like Joan Rivers, Andy Kaufman, and Jerry Seinfeld, and employed a young Wilt Chamberlain before his NBA fame.

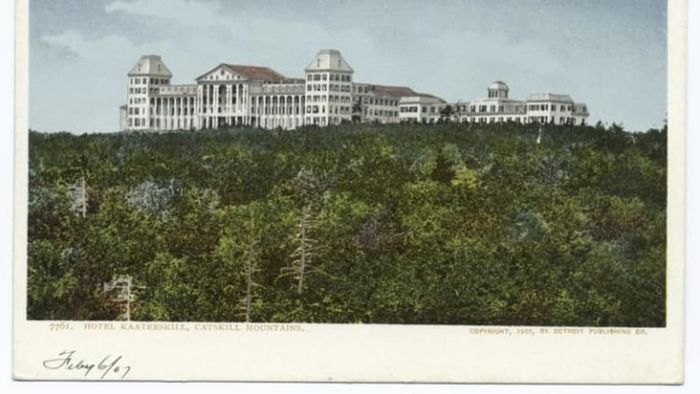

Hotel Kaaterskill, 1903-1904 | New York Public Library, Flickr // Public Domain

Hotel Kaaterskill, 1903-1904 | New York Public Library, Flickr // Public Domain

Beyond the lavish kosher dining options, these upscale New York resorts held a deeper appeal for Jewish travelers. Anti-Semitism was pervasive in the U.S. during the early 20th century, leading many vacation destinations to enforce exclusionary policies against Jews. The Borscht Belt resorts in the Catskills provided a luxurious escape where Jewish guests were assured a warm welcome.

In Dirty Dancing, explicit references to Jewish culture are scarce. Instead, the film relies on stereotypical portrayals to hint at the characters' Jewish identities. Marjorie Houseman (Kelly Bishop) embodies the overbearing Jewish mother archetype, while Lisa Houseman (Jane Brucker) fits the mold of a "Jewish American Princess."

Despite its lack of overt religious references, Dirty Dancing captures the essence of the Borscht Belt experience with remarkable accuracy.

The mambo craze depicted at Kellerman's during the summer of 1963 is rooted in reality. As documented in It Happened in the Catskills, an oral history of the Borscht Belt, the mambo dance trend was a defining feature of the 1950s and early 1960s.

Jackie Horner, a consultant for Dirty Dancing, offers a vivid account of the era. Like Penny Johnson (Cynthia Rhodes) in the film, Horner was a former Rockette and taught dance at Grossinger's from 1954 to 1986. She recalled, "We all knew the routines Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey performed in Dirty Dancing. I even brought vodka-filled watermelons to staff parties, just like in the movie."

She elaborated, "Every resort, regardless of size, maintained a dedicated dance team. Their days were filled with non-stop lessons and performances, starting at 9:30 AM and continuing until late at night. After dinner, they rehearsed for evening shows, performed at 10 PM, and then danced with guests until 1 AM."

Among the students were the so-called "bungalow bunnies," akin to Dirty Dancing's character Vivian Pressman (Miranda Garrison). Horner noted, "With husbands only visiting on weekends, these women enjoyed their freedom during the week. They took dance lessons from male instructors by day and danced with them at night, keeping their schedules packed."

Another accurate detail in Dirty Dancing was the resorts' hiring of college students for seasonal work. Characters like Robbie Gould (Max Cantor), though portrayed as antagonists, reflected the real-life presence of medical students working part-time. As Tania Grossinger wrote in her book Growing Up at Grossinger's, "College students often took summer jobs as busboys or waitresses, earning up to $1500 a season while enjoying a lively social scene."

The film's romance also rings true. These resorts were ideal settings for love stories. My own parents met at the Raleigh Hotel in South Fallsburg, New York, during Passover in 1967. Similar to Baby (Jennifer Grey) and Johnny (Patrick Swayze), my father worked as a busboy while my mother vacationed with her family. This connection led to a 15-year family tradition of celebrating Passover in the Catskills.

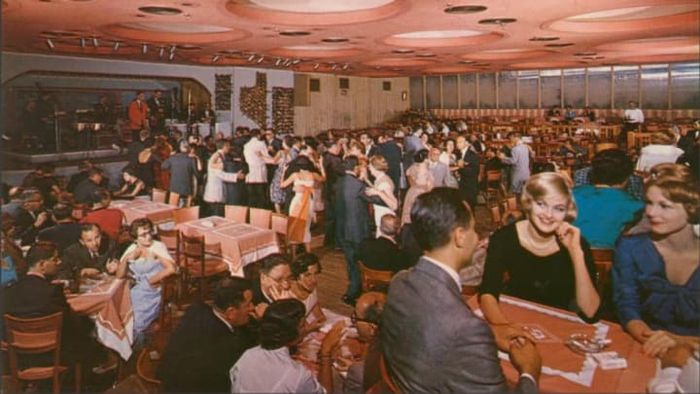

Grossinger's, 1976 | John Margolies, Library of Congress // Public Domain

Grossinger's, 1976 | John Margolies, Library of Congress // Public DomainSadly, the film also hinted at the Borscht Belt's gradual decline. While some families, including mine, continued to visit these resorts, their popularity had begun to wane by the 1960s.

Near the end of Dirty Dancing, Max Kellerman (Jack Weston) confides in bandleader Tito Suarez (Charles "Honi" Coles) about the changing times. This poignant moment, overshadowed by Swayze's iconic line, reveals Kellerman as a symbol of a fading era and culture.

Max Kellerman: "You and I, Tito, have witnessed it all. From Bubba and Zeyda [Yiddish for grandmother and grandfather] serving pasteurized milk to surviving the war and the Depression." Tito Suarez: "Times have changed, Max. So much has changed." Max Kellerman: "This time, it’s not just about change. It feels like the end. Do you think kids today want to foxtrot with their parents? They dream of Europe—22 countries in three days. Everything we built seems to be slipping away."

Max Kellerman's acknowledgment of his resort's fading glory is strikingly accurate. (His nod to the prevalence of milk at these establishments is also spot-on.) By the 1960s, affordable air travel and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 diminished the appeal of these once-exclusive retreats.

As the cultural shifts of the late 1960s loomed over the Borscht Belt resorts, the appeal of family trips to the Catskills for foxtrot lessons dwindled. While Baby might have been enthusiastic about dancing the mambo or swaying with Johnny to "Cry to Me," her interest in cha-cha-cha could have faded once Beatlemania swept the U.S. just months later.

Max's somber reflection foreshadowed the inevitable decline. Today, these grand resorts have largely vanished. Those that remain either serve ultra-Orthodox communities, like the Raleigh, or lie in perpetual ruin, as with Grossinger's.

While Dirty Dancing endures in our collective memory (or, as the song goes, "voices, hearts, and hands") through Netflix and cable reruns, the legacy of resorts like Kellerman's risks being lost without deliberate preservation.

Kutsher’s in Thompson, New York, 1977 | John Margolies, Library of Congress // Public Domain

Kutsher’s in Thompson, New York, 1977 | John Margolies, Library of Congress // Public DomainThe next time Dirty Dancing plays on TBS for what feels like the 5785th time, take a moment to empathize with Max Kellerman’s lament. As Frances Houseman once said, there was an era "before President Kennedy was shot, before the Beatles arrived," when places like Kellerman's were the epitome of cool.