The emergence of home gaming consoles during the 1980s and 1990s revolutionized the video game landscape, leaving arcades in the dust. The allure of home systems, with their growing power and convenience, rendered destination gaming nearly extinct.

Programmer Yoshihiko Ota devised an ingenious fix—a game so captivating that it left onlookers mesmerized and baffled. Enter Dance Dance Revolution, a high-energy rhythm-based game that took Japan by storm before conquering North America. Its unparalleled gameplay ensured it couldn’t be duplicated in any living room.

Taking the Stage

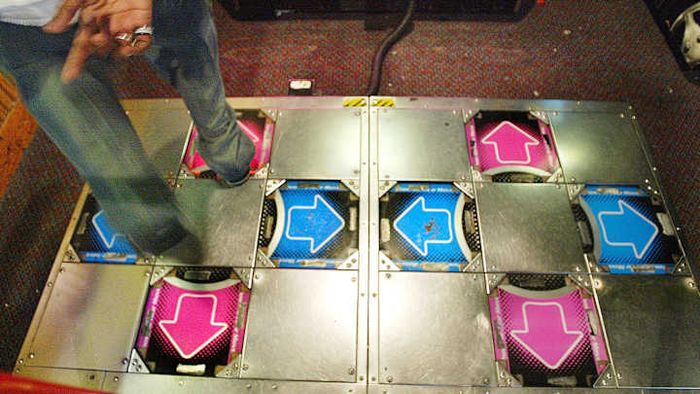

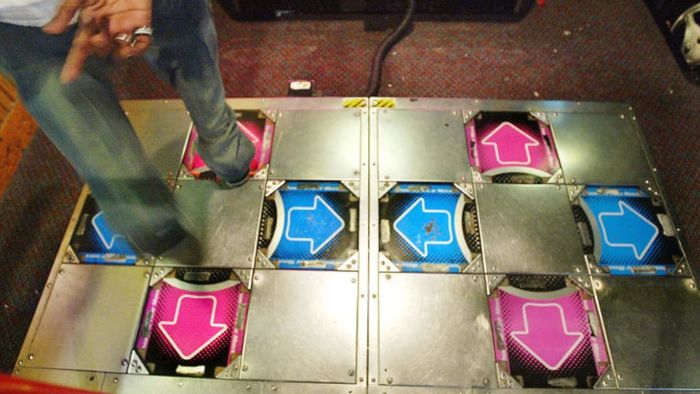

To the untrained eye, the setup of a Dance Dance Revolution station is unusual. A raised platform faces a screen, with a support bar positioned at the rear. It resembles equipment designed for post-surgery rehabilitation rather than a gaming experience.

Dance Dance Revolution marketed itself effortlessly. | Mario Tama/Getty Images

Dance Dance Revolution marketed itself effortlessly. | Mario Tama/Getty ImagesOta, a Konami game producer, recognized the need for something truly unique to revive the struggling arcade industry. His team initially worked on a fighting game, but with the dominance of Street Fighter II and Mortal Kombat, Ota realized he was merely recycling old ideas.

Inspired by their nights out at clubs and Konami’s DJ simulation game, Beatmania, Ota and his team shifted focus. They envisioned a dance simulator as the innovative solution the industry needed.

The term simulator doesn’t quite fit. Unlike games where players take on roles like soldiers, warriors, or speedy hedgehogs, Dance Dance Revolution required users to dance. Players mirrored on-screen directional cues on the platform, with speed and accuracy determining their score.

The concept of calorie-burning games wasn’t novel. Nintendo introduced the Power Pad in 1988, encouraging gamers to simulate track and field events at home. However, Dance Dance Revolution offered an emotional pull, blending gameplay with an infectious, disco-inspired atmosphere.

Konami launched Dance Dance Revolution in Japan in November 1998. For about $1.75, players of all ages could step onto the platform and lose themselves in energetic routines. Many danced for hours, drenched in sweat, challenging the notion that gaming was a passive or isolated activity.

DDR, as it became known, resonated deeply in Japan’s dance-centric culture. Kids practiced hip-hop moves while their parents frequented ballrooms. The game also thrived on its exhibitionist appeal. Players grew increasingly disheveled as they followed the game’s demanding steps, drawing crowds who cheered them on until they collapsed onto the support bar, all while hits like KC and the Sunshine Band’s “That’s the Way (I Like It)” or Carl Douglas’s “Kung Fu Fighting” blasted through powerful speakers.

The best part? Anyone could join in. If you could move, you could play. Konami sold 1000 units, an impressive feat for arcade equipment at the time.

Arrival in America

DDR made its way to the U.S. in 1999, mirroring the rise of the karaoke trend. There was an undeniable appeal in watching non-professionals take the stage, and Dance Dance Revolution essentially marketed itself. Positioned in arcades, malls, or Dave & Buster’s, the vibrant, flashing machine with enthusiastic players dancing atop it was impossible to overlook.

Dance Dance Revolution revolutionized gaming by getting players off the couch. | Mario Tama/Getty Images

Dance Dance Revolution revolutionized gaming by getting players off the couch. | Mario Tama/Getty Images“When you see DDR, you can’t help but wonder, ‘What kind of game is this?’” DDR enthusiast Cynan de Leon shared with The Ringer in 2018. “It’s this massive cabinet with flashing lights, booming music, and people stomping or even dancing on it. The energy, the music, the lights—it was unlike anything else in arcades. You either wanted to try it or laugh at the spectacle of people going all out on this machine.”

The thrill of competition quickly overshadowed any embarrassment. As DDR gained popularity, starting in California and spreading nationwide in the early 2000s, informal dance teams emerged. Skilled players added flair to their routines with knee drops, flips, and handstands. In 2000, DDR fan Shirene Olsen shared with the Los Angeles Times that she dedicated up to three hours daily to mastering moves, which often reflected regional styles.

“In California, we focus on style,” Olsen remarked. “In Chicago, it’s all about precision. The top players usually come from Chicago.”

Step Battle mode allowed players to record their routines for others to replicate, while Trick Double increased the challenge by doubling steps from four to eight. At its peak, DDR players moved so fast they appeared to be on fast-forward. One player even told the Times he shed 50 pounds through the game.

The Ultimate Dance Experience

Schools soon recognized the game’s fitness potential. By the mid-2000s, hundreds of districts began installing home versions of DDR in gyms to make physical education more engaging. While Konami benefited from expanding into schools and homes with PlayStation and Xbox versions, the arcade’s vibrant atmosphere was hard to replicate. After all, messing up a dance routine in front of your dog just didn’t have the same impact.

Despite limited updates from Konami over the years, it’s the dedicated fanbase that has sustained DDR. Players across the country have organized tournaments and even purchased their own machines, fueling a grassroots movement to integrate DDR into the eSports arena.

Whether this vision will fully materialize remains uncertain. However, one thing is undeniable: DDR, blending gaming with performance art, stands out as one of the most entertaining and spectator-friendly competitive games ever created.