By 1964, Don Knotts was seeking new opportunities. As he neared the fifth season of The Andy Griffith Show, initially planned as a five-year project, the series had already cemented his fame and brought him three back-to-back Primetime Emmys for his role as the endearingly clumsy Deputy Barney Fife. (He would later win two more in 1966 and 1967 for guest appearances.) Aware that his Mayberry days were numbered, Knotts aspired to conquer the big screen. In 1966, his dream materialized with the success of The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, a film that owed much to his Mayberry connections.

No Room for Deputies

In early 1960, as Knotts wrapped up his time on the original Steve Allen Show, he witnessed the introduction of Sheriff Andy Taylor, portrayed by his No Time for Sergeants co-star Andy Griffith, in a pilot episode of The Danny Thomas Show.

The following day, Knotts reached out to Griffith, proposing that Sheriff Taylor could use a deputy. In his book Andy and Don: The Making of a Friendship and a Classic American TV Show, Daniel de Visé suggests that Griffith saw in Knotts a chance to transfer some of the less desirable traits of Sheriff Taylor—such as his rustic, naive demeanor—to another character. This allowed Griffith to refine Taylor into a persona that better matched his own ideals. Knotts quickly joined the cast as the fourth permanent member, following Griffith, Ron Howard (Opie Taylor), and Frances Bavier (Aunt Bee).

Andy Griffith, Don Knotts, and Ron Howard. | John Springer Collection/GettyImages

Andy Griffith, Don Knotts, and Ron Howard. | John Springer Collection/GettyImagesThe series became an instant success and remained a favorite throughout its eight-season run, consistently ranking in Nielsen’s top 10. However, as revealed in Knotts’s 1999 memoir Barney Fife and Other Characters I Have Known, Griffith had always intended to leave after five years, and Knotts assumed his time in Mayberry would end as well. Financial considerations also played a role. Knotts was said to earn under $100,000 annually for his role on the show, and when he once requested a raise, he was starkly reminded that he wasn’t the lead.

As a result, Knotts explored other opportunities. He described himself as “pretty hot at the time,” receiving numerous high-paying offers for other TV projects. Yet, Knotts was determined to pursue a film career. “Keep in mind,” he noted, “television didn’t exist when I was young. Movies were my ultimate dream.”

Knotts Landing

His dream became attainable thanks to Lew Wasserman, the Universal Studios head who later propelled Jaws to blockbuster success. Wasserman admired Knotts’s performance in the 1964 film The Incredible Mr. Limpet and recognized untapped potential for cinematic stardom in him, which he aimed to nurture.

Wasserman proposed a deal to Knotts at Universal, granting him the freedom to select his own projects and even choose the writers he wished to collaborate with. Griffith complicated Knotts’s decision by deciding to remain on The Andy Griffith Show for an additional three years, lured by a $1 million yearly salary from CBS. The network reportedly offered Knotts a raise to approximately $150,000 annually, a fraction of Griffith’s earnings. However, Knotts recognized Wasserman’s offer as a rare opportunity to achieve movie stardom on his own terms.

Don Knotts, pictured here alongside co-star Frances Bavier, earned five Emmy awards from 1961 to 1967 for his role on "The Andy Griffith Show." | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Don Knotts, pictured here alongside co-star Frances Bavier, earned five Emmy awards from 1961 to 1967 for his role on "The Andy Griffith Show." | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesHowever, leaving Mayberry wasn’t as straightforward as it seemed: Once settled at Universal, Knotts required a film project. He recalled a Season 4 episode of The Andy Griffith Show, titled “The Haunted House,” which premiered on October 7, 1963. In the episode, Opie accidentally hits a baseball into the supposedly haunted Rimshaw house. Barney and Gomer (Jim Nabors) attempt to retrieve it but are terrified by what seems to be ghostly activity. The house is actually occupied by dubious characters—town drunk Otis Campbell (Hal Smith) and a local bootlegger, who staged the haunting to conceal their moonshine operation in the basement.

The episode includes several elements that would later feature in The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, such as hidden passageways, eerie paintings, and plenty of exaggerated, frightened expressions from the highly expressive Knotts.

“I realized that audiences enjoyed watching me get scared,” Knotts reflected. “So a movie centered around a haunted house seemed like the perfect fit for me.”

Sheriff Taylor to the Rescue

With The Andy Griffith Show about to take a break, Knotts enlisted two of its writers, Jim Fritzell and Everett Greenbaum, to adapt “The Haunted House” into a full-length film tailored for him. (The duo penned several iconic Mayberry episodes, such as “Convicts-at-large,” “Barney’s First Car,” and “Citizen’s Arrest”—though, notably, not “The Haunted House.”)

Producer Ed Montagne cautioned the group that blending comedy with mystery would be challenging and emphasized the need to “meticulously craft” the narrative for it to succeed. Knotts quickly thought of someone who could assist: Andy Griffith, a skilled storyteller who had refined his natural understanding of plot dynamics over five seasons of his popular sitcom. Griffith agreed to help his friend and former co-star smooth out the story’s issues, and Universal hired him for the task.

For two weeks, Griffith collaborated with Knotts, Montagne, Fritzell, and Greenbaum in a basement office at Universal to shape what would eventually become The Ghost and Mr. Chicken. The Rimshaw house was transformed into the Simmons mansion, the eerie location of a infamous murder-suicide. Knotts would play Luther Heggs, a small-town newspaper typesetter who volunteers to spend a night in the mansion and document his encounters.

Griffith frequently visited Knotts and the team during the scriptwriting process. The writers adhered closely to the framework Griffith had helped create, and they highly valued his contributions. It was Griffith who proposed turning the movie’s iconic line—“Attaboy, Luther!”—into a recurring joke rather than a single-use quip.

Once the script was approved, Knotts assisted in location scouting, collaborated with the set designer, and participated in casting sessions. Upon learning that Universal had allocated only 17 days for filming, he recommended bringing in another Andy Griffith Show alum, Alan Rafkin, to direct, praising Rafkin’s quick and efficient work style. Universal agreed, and filming commenced on July 7, 1965.

Attaboy, Don!

When Knotts viewed the final cut in a Universal screening room alongside Montagne and Rafkin, he felt uncertain about the film. He recalled watching it in “complete silence,” unsure of how to react or what to say to his colleagues afterward. Had his bold move paid off, or had he abandoned one of TV’s most beloved sitcoms to create a flop? A favorable test screening eased some of his concerns, but the real verdict would come from the paying audience.

Knotts received his answer in January 1966 during a roadshow screening of The Ghost and Mr. Chicken in New Orleans. At one point, the audience’s laughter was so overwhelming that Knotts had to request the projectionist to increase the volume. By August 1966, Montagne forecasted that the film would generate five times its $670,000 budget.

By October, Universal had secured Knotts with a five-year deal, committing to finance at least one film annually for him. Renowned The New York Times critic Vincent Canby noted that The Ghost and Mr. Chicken ranked among Universal’s top-grossing films of 1966 (though Canby quipped that it was “likely unfamiliar to most New Yorkers” and primarily drew audiences from the Midwest and South).

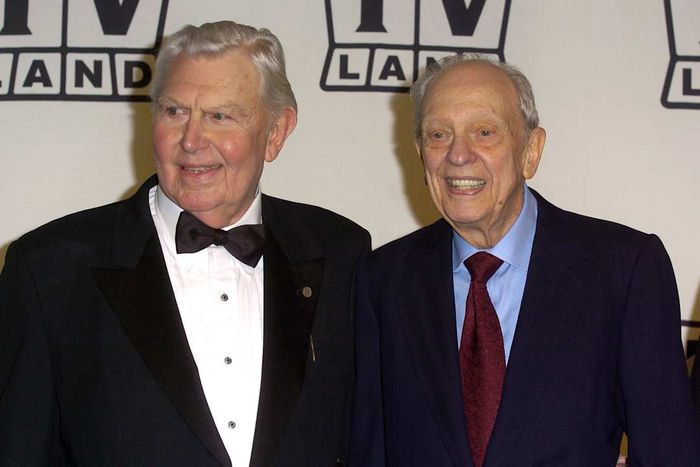

Their close friendship endured long after the iconic series concluded. | Steve Granitz/GettyImages

Their close friendship endured long after the iconic series concluded. | Steve Granitz/GettyImagesAt 42, Don Knotts had finally achieved his dream of becoming a movie star.

Although he continued working with Universal until 1971, when How to Frame a Figg fulfilled his contract, the studio chose not to extend it. By then, his popularity had diminished, and it wasn’t until he joined Three’s Company as Ralph Furley in 1979 that his career saw a resurgence. However, during the 1960s, Knotts lived his dream as a leading man on the big screen, a feat made possible by the talents of those both in front of and behind the camera on The Andy Griffith Show.

Even during his peak as a film star, Knotts never truly left Mayberry behind. He made regular guest appearances on the show, and his friendship with Griffith remained strong until Knotts passed away in 2012 at the age of 81. “You two don’t need anyone else,” Sammy Davis Jr. once remarked in 1966 when they appeared on his show, noting how they stayed close while Davis and his friends mingled. “You’ve got each other.”