James Charles Stuart ascended to the throne of Scotland on July 24, 1567, at just 13 months old, following the abdication of his mother, Mary Queen of Scots. This marked the beginning of the reign of one of Britain’s longest-serving monarchs, whose 57-year rule was notable, though not universally beloved by the public.

King James VI and I’s reign was marked by both pragmatic efforts (such as advocating for a unified Parliament and pursuing religious tolerance), diplomatic peace (including the negotiation of a treaty with Spain), and royal unity (by combining the crowns of Scotland and England). Yet his rule was also defined by autocracy (with his firm belief in the divine right of kings), fiscal extravagance (often draining the royal treasury), and a chilling cruelty (perpetrating state-backed witch hunts that claimed thousands of lives). These aspects of his monarchy reshaped society in ways that echo through history.

1. James VI and I successfully brought together the once-feuding kingdoms of England and Scotland...

The Romans’ failure to conquer the Caledonian tribes led to the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. While this barrier may have kept the tribes of the north at bay, it did not prevent William of Normandy (known as William I, “the Conqueror”) from invading Scotland in 1072, resulting in a brief truce. However, peace was short-lived, as bloody clashes such as the Battle of Falkirk (1298) and the Battle of Flodden (1513) left their mark on the centuries to follow.

Given this history, it’s no surprise that when James ascended to the English throne, peace was far from a straightforward matter. The English rejected political union with Scotland, while Scotland favored a federative relationship. James VI and I’s unification of the crowns was significant but more symbolic than actual. Although he declared himself “King of Great Britain” in 1604, during his reign, the union was mostly limited to symbolic reforms, such as the creation of the Union Jack. The real political union would only come 103 years later.

2. … but planted the seeds of the English Civil War.

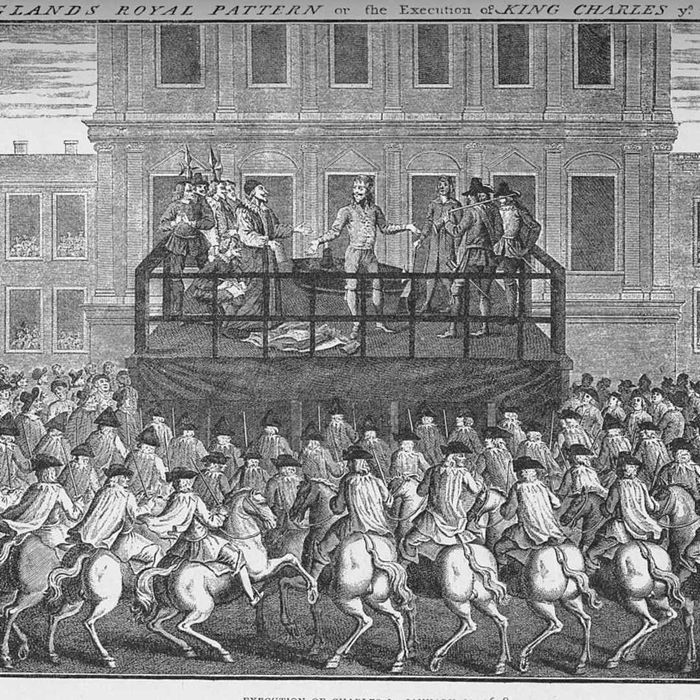

The execution of King Charles I. | Print Collector/GettyImages

The execution of King Charles I. | Print Collector/GettyImagesDespite James VI and I’s well-meaning (and personally motivated) efforts to unite the Crowns, evidence suggests that this move ignited religious and political tensions, ultimately leading to the 17th-century English Civil Wars and the execution of his son and heir, Charles I.

The union of the crowns under James VI and I left Scotland without a national figurehead. The National Library of Scotland notes, “the removal of the Scottish king from his country was a major cause of the 17th-century civil wars ... James’s union gave England a royal family it distrusted and left Scotland without the key symbol of national independence.” After claiming the English throne, James VI and I only returned to Scotland once, growing increasingly detached from his homeland. The Scots also had little affection for the shared monarch they inherited in Charles I, who, like his father, disliked ruling over two different religious systems. When Charles imposed his own prayer books on the Kirk (Church of Scotland), riots erupted in Edinburgh, escalating tensions that would eventually lead to war.

James VI and I saw himself as a ‘peacemaker,’ but the hoped-for religious tolerance during his reign failed to materialize. His peace treaty with Spain ended 15 years of costly war but alienated Protestants, who accused him of bowing to ‘popery.’ Catholics, hoping for greater freedom under the Protestant king (whose mother, Mary Queen of Scots, and wife, Anne of Denmark, were both Catholic), were likewise disappointed. After dealing with several Catholic plots against him, James lost any sympathy for their cause.

James VI and I also had frequent conflicts with Parliament, foreshadowing the issues his son, Charles I, would face. A firm believer in absolutism and the Divine Right of Kings, James defined this in The True Law of Free Monarchies, asserting that a monarch was above earthly authority. His extravagant spending, often unchecked by his Secretary of State, Robert Cecil, was a source of political tension. Charles I inherited his father’s absolutist views and disdain for Parliament, dissolving it for years at a time unless it served his interests, contributing to the Civil War and his own execution.

3. James VI and I brought peace by ending the Anglo-Spanish wars ...

English ships engaging with the Spanish Armada. | Print Collector/GettyImages

English ships engaging with the Spanish Armada. | Print Collector/GettyImagesThe latter years of Elizabeth I’s reign were dominated by hostilities with Spain. Although England triumphed over the Armada, ongoing conflicts with Spain under Elizabeth I and Philip II meant that by the time of Elizabeth’s death, England was burdened with massive debts and its government on the verge of bankruptcy. When James VI and I succeeded the English throne five years after Philip II’s death, both he and Philip III were eager for peace. In 1604, they signed the Treaty of London at Somerset House, marking the beginning of 50 years of relative peace between the two nations.

4. … but led to a decline in the wealth of merchants and privateers.

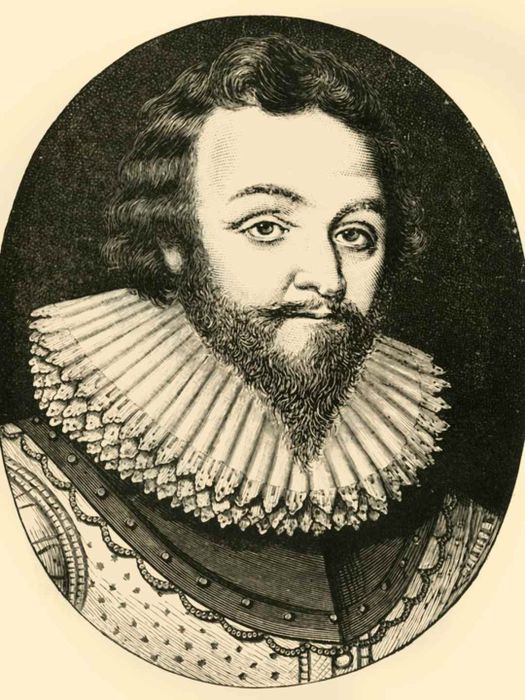

Sir Francis Drake was a renowned Sea Dog. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Sir Francis Drake was a renowned Sea Dog. | Print Collector/GettyImagesWhile James VI and I’s peace with Spain was welcomed by some, others were less enthusiastic. The wars had been profitable for certain merchants, who amassed wealth through privateering against Portuguese and Spanish ships in the southern Atlantic. In *Elizabethan Privateering*, K. R. Andrews explains that privateering was the “main form of English maritime warfare” at the time and was “closely connected with trade.” Queen Elizabeth I granted privateers, or Sea Dogs, such as Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh, official licenses to raid Spanish vessels. The wealth generated by these privateers contributed to England's economic prosperity. As one historian remarked, “the Elizabethan war with Spain … [reorientated] the English economy to the global stage.”

5. James VI and I oversaw the torture and execution of thousands accused of witchcraft.

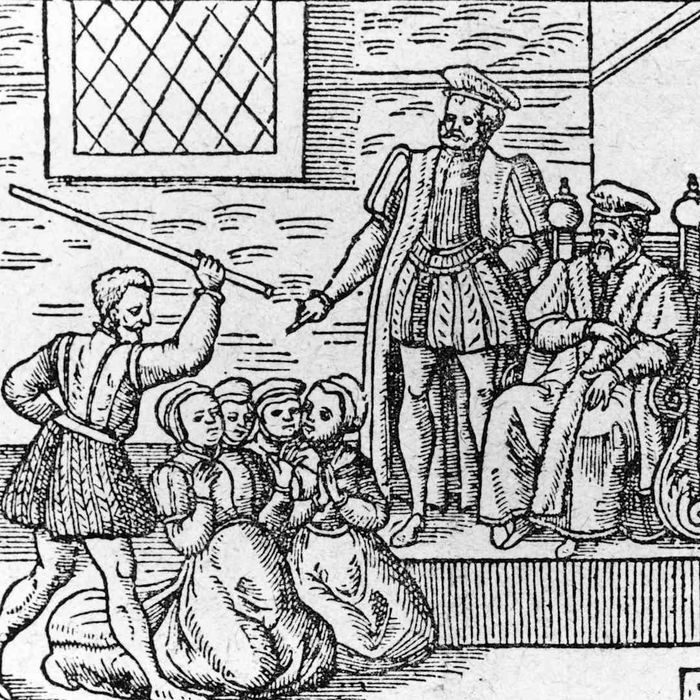

A group of alleged witches being punished in front of King James VI and I. | Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty Images

A group of alleged witches being punished in front of King James VI and I. | Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty ImagesThe Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made practicing witchcraft and consulting with witches punishable by death, but it wasn't until well after James VI and I ascended the throne that witch hunts truly began. As Allan Kennedy states in *The Trial of Isobel Duff for Witchcraft, Inverness, 1662*, “prosecutions for witchcraft were rare until the 1590s, when the first ‘panics’ occurred.”

Part of the blame for the witch hunts can be traced to a terrifying storm. While returning to Scotland after their wedding, James and Anne were caught in a violent storm that almost destroyed their ship. The disaster was blamed on witches, and some women confessed under torture that they had used witchcraft to harm the royal vessel.

The systematic persecution of suspected witches began with the North Berwick witch trials of 1590–1591. While the exact number remains unclear, estimates suggest that between 70 and 200 people were accused of witchcraft during this period, many of whom were tortured or executed.

Additional witch hunts occurred sporadically, and by the time Janet Horne—Scotland’s last person executed for witchcraft—died in 1727, it's estimated that up to 6,000 individuals (85% of whom were women, primarily from poor backgrounds) had been accused of witchcraft, with about 4,000 put to death. This figure doesn't include the approximately 1,000 victims in England and Wales. After James took the English throne, Parliament passed an Act 'against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked Spirits.'

In 2022, former First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, issued a formal apology for the “egregious historical injustice” of the witch hunts, acknowledging that “the deep misogyny that motivated it has not [been consigned to history]. We live with that still.”

6. The witch hunts initiated by James VI and I had a lasting impact on literature.

The witches appear to Macbeth and Banquo. | Print Collector/GettyImages

The witches appear to Macbeth and Banquo. | Print Collector/GettyImagesIn 1597, James VI and I published his highly influential book, *Daemonologie*. This best-seller argued for the reality of witches and the necessity of extracting confessions by any means necessary, on the grounds of religious justification. His work played a significant role in fueling the witch hunts of the time.

It is no accident that *Macbeth* was penned at the outset of James VI and I’s reign in England. As noted by the *British Library*, “Many elements of the witchcraft scenes in Macbeth align with James VI and I’s ideas on witchcraft, as outlined in *Daemonologie*,” as well as his other writings. The witches in *Macbeth*, who dance, brew potions, and keep familiars, reflect the beliefs James VI and I espoused in his publications.

In Act 1, Scene 3, Shakespeare takes things further. Referring directly to the events at North Berwick, the first witch, driven by a grudge, describes her intention to travel across the sea in a sieve (a small boat). The witches also summon a storm in this scene.

While the emphasis on witches and witchcraft in *Macbeth* likely stems from the prevailing beliefs of society at the time—beliefs largely influenced by James VI and I and his *Daemonologie*—there is debate about whether Shakespeare was simply seeking to gain favor with the king or, as the *British Library* suggests, making a more subversive statement about James's role in witch-hunting, or perhaps a combination of both.

Another work that was likely shaped by the toxic societal climate James VI and I helped create is Christopher Marlowe’s *Doctor Faustus*, which premiered in 1594. Faustus mirrors James VI and I in his rejection of theology, medicine, and metaphysics, choosing instead to pursue the “metaphysics of magicians.” Beyond surface-level comparisons, many of Marlowe’s plays delve into what it means to transcend ordinary life.

Much like *Macbeth*, *Doctor Faustus* may be more than just the work of a playwright eager to please his king. As one scholar points out, “James VI intended *Daemonologie* to make a serious contribution to occult philosophy. Similarly, Faustus can be seen not as a competent occult philosopher, but as a hapless amateur. Driven by intellectual ambition, he lacks the discipline to avoid being consumed by his own fantasies. The critique can easily be directed at the soon-to-be king of England.”

7. The Bible translation commissioned by James VI and I continues to influence literature to this day.

Translators present a Bible containing the translation commissioned by King James VI and I. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Translators present a Bible containing the translation commissioned by King James VI and I. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesThe *King James Bible* (KJV) serves as another example of James VI and I’s attempt to bring his kingdom together under one ruler and one church. With the rise of printing presses in the 15th century, countless versions of the Bible had been produced, causing division among different factions, especially the Anglican bishops who felt threatened by the popular *Geneva Bible*—one of the most widely-read versions when James VI and I ascended the throne.

In 1604, James VI and I decided to unite his subjects under a single, universally accepted text that would correct the issues in certain versions while preserving the essence of the original style. This was a practical solution to the religious tensions of the time, though it also had personal motivations: by commissioning the translation, James sought to assert his authority over religious matters and solidify his legacy as a revered king.

Published in 1611, the KJV marked the arrival of a *democratized Bible*, making religious teachings accessible to the common people in a language they could understand for the first time. It quickly spread across Europe and became the most widely-read Bible version in English-speaking countries.

Unfortunately for James VI and I, his translation made certain passages accessible to the people—passages that were rarely quoted in church. These passages revealed that monarchs, too, are bound by the laws of God, a direct contradiction to James VI and I’s belief in the divine right of kings. While this did not directly affect James, who passed away before the KJV gained popularity, it may have influenced his son. Charles I’s belief in the divine right of kings played a significant role in the Civil War, a belief that was clearly undermined by his father’s Bible.

Even 412 years after its publication, the KJV remains the most widely-read version of the Bible and is one of the most printed books ever. Known for its literary excellence, its influence can be seen in the works of writers such as *John Milton*, *Robert Burns*, and *John Steinbeck*. The Bible is regarded as one of the most important texts in history, contributing 257 phrases to modern English idioms, including “a wolf in sheep’s clothing” and “by the skin of your teeth.”