In today's world, it's common to hear people demanding "more democracy" or declaring, "this is what democracy looks like" at protests or rallies. At its core, "democracy," derived from demos (meaning "people") and kratos (meaning "power"), simply means "rule by the people." The word's Greek roots emphasize that the concept of democracy was first given to the world by Ancient Greece, particularly Athens.

However, when people today call for "democracy," what they typically seek is direct democracy within a parliamentary system. This type of government is more aligned with British traditions than ancient Greek practices. If we were to recreate the democracy of Ancient Athens today, many would likely label it "fascism!"

The history of democracy is far more complex and murky than we might assume, filled with numerous inaccuracies and lesser-known facts. The following 10 examples reveal that many popular beliefs about the democracy in Ancient Athens are, in fact, false.

10. A Restricted Democracy

The ancient aristocrats of Athens held a deep skepticism towards the common people. This sentiment was later mirrored by the Roman patricians and the architects of the US Constitution. The elite believed that voting rights in Athenian elections should be strictly limited to a select portion of the population, specifically propertied men who had served in the military.

However, due to the influence of demagogues and tyrants, voting rights gradually expanded. After Solon’s reforms, the aristocrats acknowledged that all men over the age of 20 could participate in elections, which amounted to roughly 10 percent of the city's total population. Despite this, two large groups—women and slaves—remained excluded from the voting process, with slaves comprising around 40 percent of the population who were denied suffrage.

The final significant limitation on Athenian democracy was the issue of citizenship. Only citizens of Athens were granted the right to vote, meaning that individuals with non-Athenian parents were disenfranchised.

9. A Profound Paradox

One of Athens' most influential leaders was Cleisthenes, who served as the city's archon from 525–524 BC. Often regarded as the principal founder of Athenian democracy, Cleisthenes earned this distinction due to his support of the popular Assembly, a stance that opposed the powerful Athenian aristocrats.

Ironically, Cleisthenes himself came from noble roots, being a member of the esteemed Alcmaeonid family. This family produced some of the most influential tyrants during the Archaic period of Greek history in Athens.

Cleisthenes' reforms were instrumental in establishing citizenship, rather than tribal membership, as the key requirement for suffrage. Another layer of irony here is that Athens ultimately decreed that only the sons of Athenian citizens were allowed to vote. This law would have excluded Cleisthenes from voting, as his mother was a citizen of Sicyon.

8. The Dawn of the First Democratic Empire

Many people mistakenly believe that ‘true democracies’ cannot coexist with imperialism. The history of Great Britain, the most prominent advocate of parliamentary democracy and the largest imperial power ever, should serve as proof that democratic nations can indeed be conquerors.

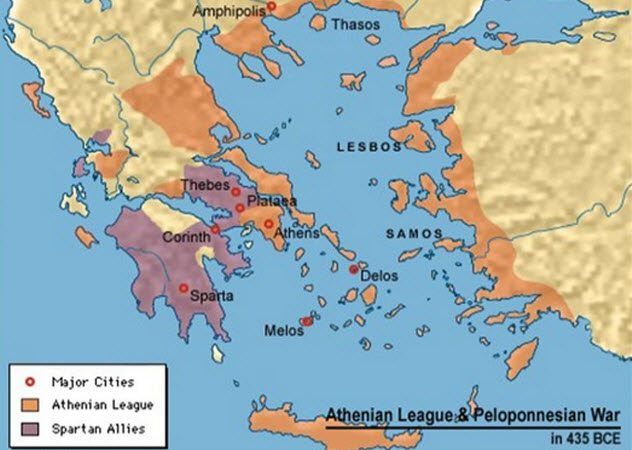

In reality, Athens can rightly be regarded as the first democratic empire. Though officially named the Delian League, and ostensibly a confederation of pro-Athens city-states, the league was essentially an imperial enterprise.

The Delian League was founded after the Greek victory over the Persians at Salamis in 480 BC. Given the pivotal role of the Athenian Navy in that victory, several city-states pledged to a security alliance led by Athens, headquartered on the island of Delos.

At its peak, the league comprised about 200 city-states, with most contributing annual tributes to Athens. In exchange, Athens used the league as a means to further its expanding commercial and colonial empire across the Mediterranean. The Delian League would later be called upon to battle Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, Athens’ greatest rival.

7. The Democracy of Sparta

Though Athens is often credited with being the birthplace of democracy, it was not the first Greek city-state to experiment with this system. Sparta, its fiercest competitor, also embraced democracy. Often portrayed as a militaristic and authoritarian counterpart to Athens' democratic ideals, Sparta’s government implemented the earliest known democratic constitution, which by many accounts, predates Athens’ version by as much as 50 to 200 years.

One key distinction between the democracies of Sparta and Athens was the role of monarchy. Unlike Athens, which lacked a monarchy, Sparta maintained its royal tradition but heavily restricted its powers within the framework of its constitution.

The Spartan political structure was unique, featuring a Council of Elders that included the two hereditary kings and 28 elected officials, as well as a lower house designed to represent and safeguard the interests of the Spartan citizenry.

Though Sparta's harsh military discipline and its oppressive slavery system would not be seen as particularly democratic by today's standards, this war-focused city-state can rightfully claim to have been the first participatory democracy in mainland Greece.

6. Other Democratic States in Ancient Greece

Apart from the democracies in Sparta and Athens, other notable democratic city-states existed, such as Argos and the island of Rhodes. The democracy in Argos, though brief from 470 to 460 BC, earned the city-state a strong reputation for its democratic practices.

The renowned Greek playwright Aeschylus praised Argos by portraying its hero as a major figure of the people, stating, “the people, which rules the city.” Nevertheless, despite such commendations, Argos embarked on a campaign of conquest, including the cities of Tiryns and Mycenae.

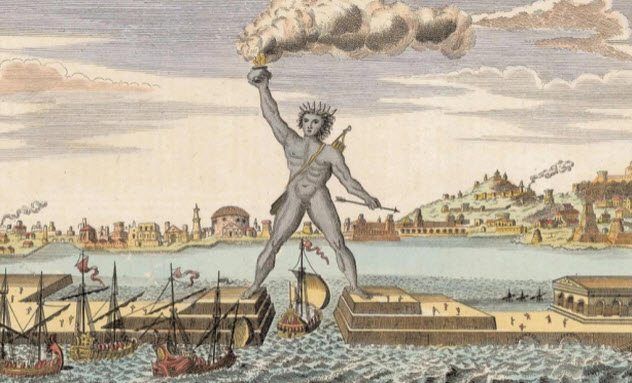

Democracy also prospered on the island of Rhodes, which is famously known for the towering “Colossus” statue. This island was a democratic state with a rich historical background before its conflict with Athens during the Social War.

The eminent Athenian orator Demosthenes extolled the liberty of the Rhodians, but it was Athenian imperialism that likely led Rhodes to abandon democracy in favor of oligarchy. The city's troubled history of conquest, first by the Persians and later by Alexander the Great’s Macedonian forces, coupled with unfortunate alliances (with Athens and Sparta), sealed its fate and caused the end of its democracy.

5. Democracies Beyond Greece

The concept of democratic city-states wasn't unique to Greek lands. Although rare, the few democracies outside Greece were founded by Greek colonists. In Sicily, the prominent Greek city of Syracuse briefly embraced democratic governance.

While Syracuse is primarily known for its despotic rulers, the city actually witnessed a civil war in which its tyrant was ousted. Soon after, a democracy was established in the city, which was the largest and most influential Greek city-state in Sicily.

Founded by Greek colonists from Corinth, Syracuse received assistance in its democratic uprising from other Sicilian city-states, including Acragas, Himera, Selinous, and Gela. Syracuse's democracy, though, had imperial ambitions and controlled much of the southeastern part of Sicily. It also had a significant slave population made up of non-Greek Sicel natives.

To the north, Metapontum, another Greek city-state, was also democratic. Located in the present-day Italian province of Matera, Metapontum was founded by Achaean settlers. The city became a commercial hub and may have been the first democracy in the Greek world. Even after Athens fell, Metapontum retained its independence, supporting Hannibal during the Second Punic War.

4. Military Dictatorships

Warfare was a constant feature in ancient Greece, deeply ingrained in daily life for its citizens. As a result, Greek city-states often saw it as logical to appoint politicians as generals or even dictators in times of crisis.

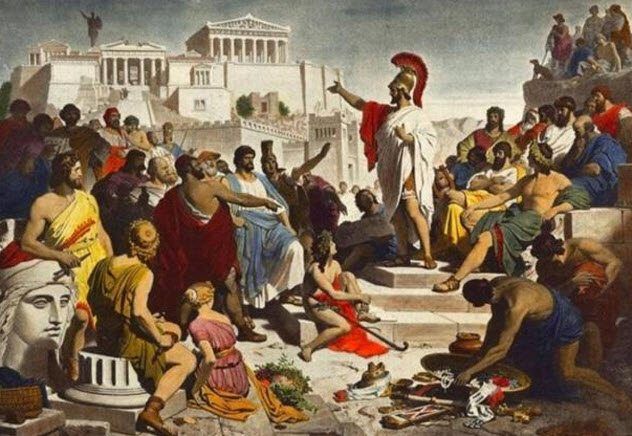

In Athens and other Greek cities, the strategus was a military officer elected to oversee various tasks, not all of which were purely military. Athens even established a council of 10 strategi during its transition from a tribal society to a city-state based on citizenship.

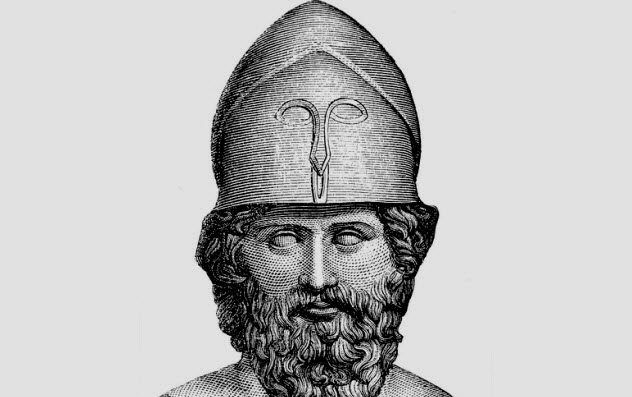

The most well-known strategus in Greek history was Themistocles, the Athenian general who led the victory against the Persians at Salamis. Another famous Athenian strategus was Pericles, who commanded the Athenian and allied forces against the Spartans during the Peloponnesian War.

Above the strategus were the archons. While 'archon' generally referred to leaders, the archons in Athens were the principal magistrates responsible for making significant civil and military decisions. The archon basileus oversaw religious sacrifices, while the archon polemarchos was the general whose vote played a pivotal role in internal discussions.

3. The Democratic Plays

Before the rise of democracy, ancient Greece was largely a tribal society where the rule of law was limited. In matters of justice, blood feuds were frequently used to resolve conflicts, with these feuds sometimes continuing for generations.

Then, in the fifth century BC, the Greek playwright Aeschylus wrote his Oresteia trilogy. The three plays—Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides—depict pre-democratic Greece as a violent and blood-soaked world.

The plays focus on the house of Agamemnon, the hero of the epic Greek poem The Iliad. After Agamemnon is killed by his wife, Queen Clytemnestra, their son, Orestes, returns to Argos to avenge his father's death. Orestes ultimately murders his mother, which brings about the wrath of the Furies.

In the final play, Orestes is put on trial for his crimes. The goddess Athena rules in his favor, pacifying the Furies and sending them to the underworld. The Oresteia as a whole celebrates the emergence of democratic law, and some see it as a deliberate propaganda piece aimed at convincing skeptical Greeks of the superiority of law, the Athenian constitution, and the court system.

2. The Significance of Tyrants

Many perceive tyrants as the antithesis of democracy. After all, the most notorious tyrants of the 20th century were all opposed to democratic ideals, whether communists like Joseph Stalin and Pol Pot, or fascists such as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. This revisionist view obscures the fact that tyrants and demagogues have sometimes advanced the democratic cause more effectively than elected leaders.

This was certainly true in ancient Greece. The poet-tyrant Solon implemented far-reaching reforms in sixth-century Athens. Among these, Solon liberalized slave laws, freeing many slaves, sought to balance political power between the aristocracy and the impoverished majority, and established a new class structure in Athens based on earned wealth. All of these reforms were carried out with the consent of the Athenian people.

One of Solon's other major reforms was the creation of the Boule, a council of 400 Athenian citizens that functioned like a modern-day senate. Another significant democratic tyrant was Peisistratos, who championed the cause of the lower classes in Athens. In hindsight, both Solon and Peisistratos' actions can be seen as early examples of democratic populism.

1. A Brief Existence

Despite the accolades lavished on ancient Athens, the 'Golden Age of Greek Democracy' was remarkably short-lived. At its peak, Athenian democracy flourished from 480 to 404 BC.

During this period, Athens stood as the undisputed leader of the Greek world, with colonies extending as far as Spain and Crimea. It was also the wealthiest Greek city, known for both its prosperity and its cultural influence.

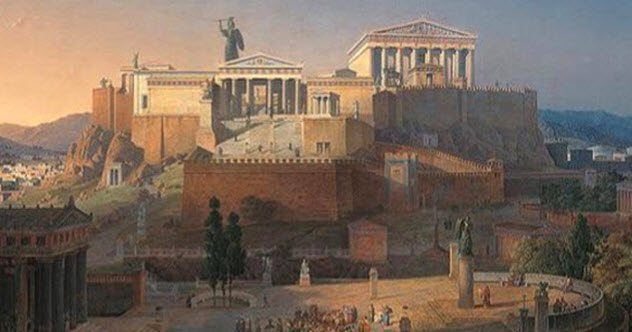

Athens was the birthplace of great poets, playwrights, and philosophers, including Sophocles, Plato, Socrates, Euripides, and Aristophanes. The city was also home to architectural masterpieces like the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the Acropolis.

Sadly, the 'Golden Age' came to an end due to Athens' own arrogance. First, Sparta's victorious army triumphed over Athens in the Peloponnesian War. Later, following a broad revolt against Spartan authority, Athens experienced a brief resurgence as the dominant power in Greece.

However, a catastrophic invasion of Sicily led by Alcibiades devastated the Athenian Navy beyond recovery. By the fourth century BC, the once-small kingdom of Macedonia succeeded in conquering much of Greece and became the leading force in spreading Hellenic culture across Africa and Asia.