Almost two years ago, we published a list of everyday inventions. It became quite popular and debunked at least one myth, particularly the origin of peanut butter. Now, we present the second part of the series, exploring ten additional items that we all encounter daily. These are the kinds of things we often take for granted, and we’d likely have no idea who created them if asked.

10. Garden Gnomes

The creation of garden gnomes dates back to the mid-1800s in Gräfenroda, a town in Thuringia, Germany, renowned for its ceramics. Philip Griebel started by making terracotta animal figures as decorations and later designed gnomes inspired by local myths. These gnomes were believed to help with garden work at night, and the tradition quickly spread across Germany, France, and England, wherever gardening was a beloved pastime. Griebel’s descendants continue to craft these gnomes, and they are now the last of the German producers. In 1847, Sir Charles Isham introduced garden gnomes to the UK, bringing 21 terracotta figures back from Germany and placing them in the gardens of his home, Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire. Only one of these original gnomes remains: Lampy, who is on display at Lamport Hall and is insured for one million pounds.

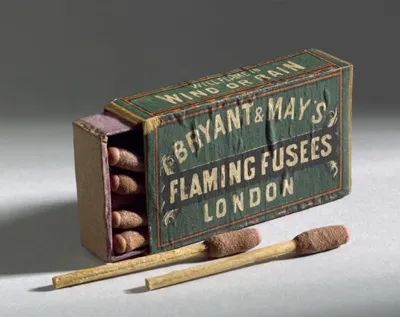

9. Friction Matches

While matches have existed in China since the 6th century and in Europe from the 16th century, it wasn’t until the 1800s that friction matches, as we know them today, were invented. The first true “friction match” was created by English chemist John Walker in 1826. Although Robert Boyle and his assistant Godfrey Haukweicz experimented with phosphorus and sulfur in the 1680s, their attempts failed to yield practical results. Walker, however, discovered that a combination of stibnite, potassium chlorate, gum, and starch could ignite by striking it against any rough surface. He originally called these matches “congreves,” but the patent was acquired by Samuel Jones, and they became known as lucifer matches (a term still used in the Netherlands). In 1862, British matchmakers Bryant and May began mass production of the red-tipped matches we use today, after the Lundström brothers from Sweden patented the process.

8. Contact Lenses

Contact lenses are surprisingly older than most of us think. In 1888, the German physiologist Adolf Eugen Fick created and successfully fitted the first functional contact lens. While in Zürich, he described crafting afocal scleral contact shells, which rested on the less sensitive tissue around the cornea. He experimented with fitting them first on rabbits, then on himself, and finally on a small group of volunteers. These lenses were made of heavy blown glass and measured 18–21mm in diameter. Fick filled the space between the cornea and the glass with a dextrose solution. His lens was large, cumbersome, and could only be worn for a few hours at a time. It wasn’t until 1949 that the first lenses, which only covered the cornea, were produced and allowed for much longer wear.

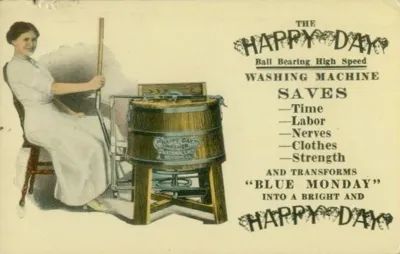

7. Washing Machine

The first patent for a non-electrical washing machine was granted in England in 1692. Almost two centuries later, Louis Goldenberg of New Brunswick, New Jersey invented the electric washing machine, during the late 1800s to early 1900s. At the time, he worked for the Ford Motor Company, and since all inventions made under Ford's contract belonged to the company, the patent should have been credited to Ford or Louis Goldenberg. Alva J. Fisher has often been mistakenly credited with the invention of the electric washer, but the US Patent Office shows at least one patent issued before Fisher’s US patent number 966677.

6. Soda Can

Early metal beverage cans were made of steel and lacked pull-tabs. Instead, they were opened with a can piercer, a tool that resembled a bottle opener but had a sharp point. The method involved punching two triangular holes in the lid—one large for drinking, and a smaller one to let air in. This type of opener was often called a churchkey. As early as 1936, inventors were filing patents for self-opening can designs, but the technology at the time rendered these ideas unfeasible. Later advancements saw the ends of cans being made from aluminum instead of steel. In 1962, Ermal Cleon Fraze from Dayton, Ohio, invented the integral rivet and pull-tab (also known as rimple or ring pull), which had a ring attached at the rivet for easy pulling and detached completely to be discarded. These were eventually replaced almost entirely by the stay tabs we use today. The stay tab (also referred to as the colon tab) was invented by Daniel F. Cudzik of Reynolds Metals in Richmond, Virginia, in 1975.

5. Condoms

The first rubber condom was created in 1855. For many years, rubber condoms were produced by wrapping raw rubber strips around penis-shaped molds, then dipping the molds into a chemical solution to cure the rubber. In 1912, a German inventor named Julius Fromm developed a new and improved method for making condoms by dipping glass molds into raw rubber solution. This process, called cement dipping, involved adding gasoline or benzene to liquefy the rubber. These condoms were reusable. In 1920, latex—rubber suspended in water—was invented. Latex condoms were simpler to produce than cement-dipped rubber condoms, which had to be smoothed and trimmed. The use of water instead of gasoline or benzene eliminated the fire risks previously associated with condom factories. Latex condoms also offered better performance for consumers: they were stronger, thinner, and had a shelf life of five years (compared to rubber condoms' three months).

4. Tin Foil

Foil, originally made from thin sheets of tin, was widely used before aluminum foil became more common. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tin foil was the standard, though some people still use the name for the newer aluminum product. Compared to aluminum, tin foil is stiffer and has a tendency to impart a slight tin flavor to food wrapped in it. This is a major reason why it has been largely replaced by aluminum and other materials for food wrapping. Interestingly, the first audio recordings on phonograph cylinders were created using tin foil. Tin foil was phased out starting in 1910 when the first aluminum foil rolling plant, 'Dr. Lauber, Neher & Cie., Emmishofen,' was established in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland.

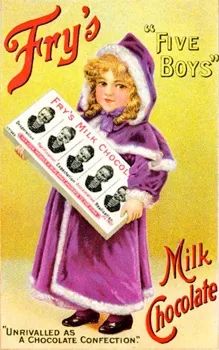

3. Chocolate Bars

Until the 19th century, candy was typically sold in bulk, measured by weight, and in small pieces that would be bagged upon purchase. The introduction of chocolate as a treat that could be eaten on its own—rather than solely used for beverages or desserts—led to the creation of the first chocolate bars. In 1847, Fry’s chocolate factory in Union Street, Bristol, England, produced the first-ever chocolate bar suitable for widespread consumption. The company went on to create the Fry’s Chocolate Cream bar in 1866 (which, in my opinion, is the best chocolate bar in the world). Over the next few decades, more than 220 products were launched, including the first chocolate Easter egg in the UK in 1873 and the Fry’s Turkish Delight (or Fry’s Turkish bar) in 1914. By 1919, the company merged with Cadbury’s chocolate, forming the British Cocoa and Chocolate Company.

This article is licensed under the GFDL as it contains quotations from Wikipedia.

2. Shampoo

The word 'shampoo' originally referred to a head massage in several languages of North India. Both the term and the practice were brought to Britain from colonial India. In 1814, a Bengali entrepreneur named Sake Dean Mahomed introduced the practice to Britain, opening 'Mahomed’s Indian Vapour Baths' in Brighton with his Irish wife. In the early days of shampoo, English hair stylists boiled shaved soap in water and added herbs to give the hair a shiny and fragrant finish. The first known shampoo maker was Kasey Hebert, and the origin of the product is now attributed to him. Initially, shampoo and soap were quite similar, both containing surfactants, a type of detergent. The modern form of shampoo as we know it today emerged in the 1930s with Drene, the first synthetic (non-soap) shampoo.

1. Ballpoint Pen

The first patent for a ballpoint pen was granted on 30 October 1888 to John J. Loud, a leather tanner. He was trying to create a writing instrument that could mark leather, something that the fountain pen of the time couldn’t manage. The design featured a small rotating steel ball held in place by a socket. Half a century later, with the assistance of his brother George, chemist László Bíró began working on a new type of pen. Bíró’s design included a tiny ball at the pen’s tip that could rotate freely in its socket. As the pen moved across paper, the ball picked up ink from the cartridge and transferred it onto the paper. Bíró filed a British patent for this design on 15 June 1938. Early versions of pens struggled with ink flow, either leaking or clogging due to the ink’s viscosity and relying on gravity to deliver the ink. Gravity-dependent flow was problematic, requiring the pen to be nearly vertical. The Biro pen resolved this issue by pressurizing the ink column and using capillary action for ink delivery, ensuring a smooth flow.