The legendary Sunken Lounge at the TWA Hotel features a vintage split-flap departures board by Solari di Udine and overlooks the meticulously restored 1958 Lockheed Constellation "Connie." TWA Hotel/David Mitchell

The legendary Sunken Lounge at the TWA Hotel features a vintage split-flap departures board by Solari di Udine and overlooks the meticulously restored 1958 Lockheed Constellation "Connie." TWA Hotel/David MitchellBefore the era of TSA, full-body scanners, and overcrowded flights, air travel was an exhilarating and refined experience. Consider the Trans World Airlines (TWA) terminal at New York International Airport. In 1956, Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen was commissioned to design this terminal, then located at Idlewild, now known as John F. Kennedy International Airport.

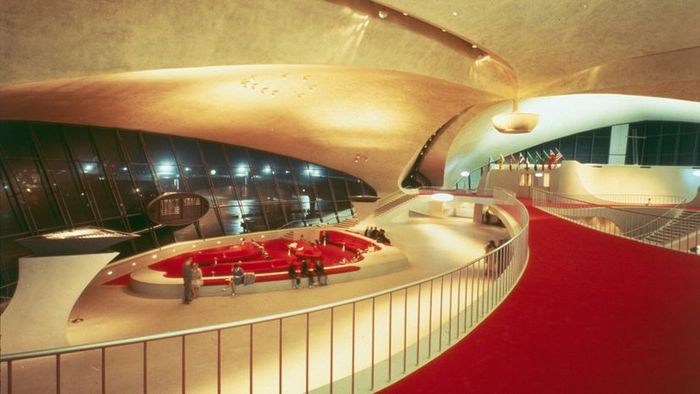

A symbol of the jet age, the TWA Flight Center debuted in 1962, showcasing groundbreaking architecture and cutting-edge design. Its striking winged roof and sweeping interior curves made it both a functional structure and a monumental work of art.

Unfortunately, Saarinen, the visionary behind the St. Louis Gateway Arch and numerous other iconic designs, passed away in 1961 at just 51 years old, never witnessing the final realization of his masterpiece.

The TWA Flight Center

While the TWA Flight Center was a marvel of its era, it faced challenges adapting to modern demands. Conceived in the 1950s during the propeller plane era and anticipating supersonic travel, the structure became outdated. Richard Southwick, a partner and historic preservation director at New York's Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners, notes that the building was ill-suited for larger aircraft like the 747. Its waiting areas, designed for about 100 passengers, were also insufficient for modern air travel needs.

The TWA Flight Center, as it appeared in 1956.

Balthazar Korab

The TWA Flight Center, as it appeared in 1956.

Balthazar KorabBeyer Blinder Belle joined the project in 1995, shortly after the building was designated a historic landmark, as the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey sought solutions for its preservation. By that time, TWA had stripped the interior, leaving it vastly different from Saarinen's initial vision.

In 2001, TWA sold the structure to American Airlines, but the aftermath of 9/11 led to its abandonment, Southwick recalls. The building remained empty and outdated, its 1960s charm hidden away, with demolition looming. "For preservationists, vacancy is a building's worst enemy," Southwick explains. "A structure loses its vitality without activity."

How They Revived a Landmark

Rather than facing demolition, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Southwick's firm collaborated with the Port Authority to draft a proposal aimed at revitalizing the TWA Flight Center.

However, challenges arose. Developers were hesitant due to high costs, demanding renovations before committing. The Port Authority invested approximately $20 million, while Beyer Blinder Belle undertook the restoration of key areas.

The initiative still involved demolition, but only the later additions to the structure, post-Saarinen's original design, were removed. This paved the way for the hotel's development and ensured the project's financial viability.

"A total of 22 government agencies and more than 180 firms collaborated tirelessly for five years to bring this project to life," explains Kaunteya Chitnis, senior vice president of acquisitions and development at MCR, the hotel project's developer. "It represents a significant public-private partnership."

Guests at the Sunken Lounge or the Paris Café by Jean-Georges can enjoy cocktails while watching planes take off.

TWA Hotel/David Mitchell

Guests at the Sunken Lounge or the Paris Café by Jean-Georges can enjoy cocktails while watching planes take off.

TWA Hotel/David MitchellThe TWA Hotel Today

Today, the former terminal serves as the lobby for the TWA Hotel. It features 521 guestrooms connected via a tube to JFK Terminal 5, offering a nostalgic journey back to the 1960s, complete with modern amenities like wifi. The hotel is divided into two wings: Saarinen and Hughes, the latter named after aviation pioneer Howard Hughes, who was the majority stakeholder in TWA when the Flight Center first opened.

The original baggage claim area has been transformed into a ballroom, but "everything else remains in its original location," notes Southwick. Spaces such as the London Bar, Lisbon Lounge, and Paris Café have kept their historic names.

"We undertook a meticulous restoration of the space," Southwick explains. The 1960s TWA Flight Center is a showcase of mid-century modern design, featuring Eames furniture, Knoll fabrics, and a Noguchi fountain. During Beyer Blinder Belle's renovation, the iconic sunken seating area had to be recreated using original drawings. For the lounge, guestrooms, and event spaces, Knoll furniture was sourced, including Saarinen-designed classics like the Womb and Tulip chairs.

The Paris Café by Jean-Georges offers breakfast, lunch, and dinner, accompanied by stunning views.

TWA Hotel/David Mitchell

The Paris Café by Jean-Georges offers breakfast, lunch, and dinner, accompanied by stunning views.

TWA Hotel/David MitchellMuch of the iconic red carpet had disappeared, and the remnants were heavily faded. The team visited Yale University, where some of Saarinen's archives are stored, and discovered a collection of samples, including pristine carpet that had never been exposed to light.

"The color remained remarkably vibrant," Southwick remarks about the Chili Pepper Red, which now adorns the Sunken Lounge — currently a Gerber Group bar — as well as hotel corridors and other spaces. Check-in occurs at the original departure desks, now operated via tablets. Restored penny tile flooring and a handcrafted split-flap departures board by Solari di Udine perfectly capture the mid-century airport aesthetic.

Guests can gaze through the large windows at the Connie, a 1958 Constellation airplane transformed into a cocktail lounge. The ambiance is undeniably reminiscent of the "Mad Men" era.

Beyond its 512 rooms, the TWA Hotel boasts numerous dining and drinking venues: the Paris Café by Jean-Georges, The Sunken Lounge, The Pool Bar, the Connie Cocktail Lounge, a Food Hall, and Intelligentsia Coffee. The Reading Room, a library and bookstore in collaboration with Phaidon and Herman Miller, offers additional charm, alongside various shopping options. A 10,000-square-foot fitness center, open 24/7, holds the title of the world's largest airport gym.

The hotel not only showcases history through its architecture and design but also hosts several exhibitions. These include a TWA Museum, a display of TWA uniforms over the decades, an exhibit on Hughes, and, naturally, a tribute to Saarinen.

The guestrooms at the TWA Hotel feature the second-thickest glass globally, ensuring a tranquil stay.

TWA Hotel/David Mitchell

The guestrooms at the TWA Hotel feature the second-thickest glass globally, ensuring a tranquil stay.

TWA Hotel/David MitchellStay an Hour, Stay Overnight

Situated at a 24-hour international airport — the fifth busiest in the U.S. — the TWA Hotel provides travelers with a Day Stay option for short-term relaxation. Available in four-hour blocks or longer, time slots such as 7 to 11 a.m., 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., or noon to 6 p.m. allow passengers to refresh, enjoy the pool, visit the gym, or rest between flights.

Local travelers can also use the hotel for overnight stays before early morning flights, avoiding the hassle of early drives or traffic delays. According to MCR's Chitnis, the average stay at the TWA Hotel is just 1.1 nights.

Naturally, the hotel itself is a major draw. "The Connie has been a massive attraction; it's one of only four left globally," Chitnis notes. "But the Flight Center has been the star of the project. No photograph can truly capture the sensation of standing inside that building."

During the 2015 Open House New York Weekend, a three-day event where New York City opens its landmark buildings for tours and events, over 10,000 visitors explored the building in just four hours. The fascination with the structure remains strong, offering architecture enthusiasts, Saarinen admirers, and aviation lovers the chance to visit year-round.

"I hope guests at the TWA Hotel leave with a renewed appreciation for the golden age of air travel," says Southwick. "When flying wasn't just comfortable and convenient, but truly enjoyable."

The restoration of the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport was a collaborative effort involving 22 government agencies and more than 180 firms.

TWA Hotel/David Mitchell

The restoration of the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport was a collaborative effort involving 22 government agencies and more than 180 firms.

TWA Hotel/David MitchellThe TWA Flight Center's interior is a stunning tribute to mid-century modern design, showcasing innovative reimaginations of traditional shapes and materials. However, the building itself is a "structural marvel," as Southwick describes it. Remarkably, the entire Flight Center is supported by just four columns, each bearing the weight of two corners of the building's lobes. Southwick likens the structure to a bird with expansive wings balanced on slender legs or a dinosaur with immense weight supported by two central limbs.