[b]When startled, fainting goats stiffen up and collapse. It may take a few seconds before they are able to move again.

John Foxx/Getty Images

[b]When startled, fainting goats stiffen up and collapse. It may take a few seconds before they are able to move again.

John Foxx/Getty ImagesGoats typically spend their days eating, climbing, butting heads, and balancing on high places. However, one special breed of goat stands out for a unique behavior: they freeze up and appear to faint.

Videos of these fainting goats continue to circulate on social media and animal-focused TV shows. After all, what’s funnier than seeing a group of goats topple over in unison every time a farmer approaches with an umbrella?

Despite their dramatic falls, these goats (also known as myotonic goats, "Tennessee stiff-legs," "Tennessee wooden-legs," "nervous goats," and "fall-down goats") aren’t just fearful or faint-hearted. In reality, they don’t actually faint or lose consciousness. Their muscles lock up due to a congenital condition called myotonia congenita or Thomsen's disease, causing them to freeze when startled without immediately relaxing. Imagine a full-body cramp, but without the pain.

The intensity of the condition can vary. Some fainting goats freeze up every time they’re startled, while others do so less often. Over time, the symptoms tend to diminish, and some goats learn to cope with the condition better. Younger goats are more likely to collapse when startled, but as they age, many become able to avoid falling during these episodes. They simply stiffen their legs and run away from potential danger. Older goats also grow more accustomed to their surroundings and are less easily startled.

In this article, we will explore this unusual breed of goat in greater detail. We'll dive into how myotonic congenita functions and the impact it has on the goats' daily lives. We'll also explore how they became classified as a distinct breed and why anyone would intentionally breed them to encourage their fainting episodes.

Why Fainting Goats Faint

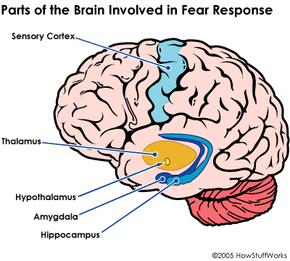

To better understand why a myotonic goat faints when frightened, it helps to first look at how the body reacts under normal circumstances. If someone were to chase a goat not affected by myotonia congenita, its eyes and ears would perceive the threat and send the information to the brain. The brain would then signal the skeletal muscles (such as those in the legs and neck) to tense up, triggering what is known as the fight or flight response.

Imagine how it feels to be surprised or startled by a friend. Your voluntary muscles contract and tighten for a brief moment. This reaction occurs because your brain is signaling your muscles to prepare for a potential confrontation or flight in response to an immediate threat.

Typically, muscle tension is followed by a quick relaxation of the affected muscles, allowing a normal goat to turn and flee from danger. However, with myotonia congenita, the muscles remain tensed for an extended period before gradually relaxing. Imagine the sensation of muscle tension after a sudden shock, but instead of lasting a moment, it stretches on for 10 to 20 seconds.

At the cellular level, the voluntary muscles of myotonic animals receive an electric signal from the brain to tense and hold that tension instead of releasing it, much like a skipping record that can’t continue properly.

This occurs because myotonia congenita affects a specific gene known as CLCN1 (Chloride Channel 1). This gene plays a key role in producing and regulating proteins essential for the flexing and relaxing of muscles. Positively charged sodium ions carry the brain's message for muscles to contract, while negatively charged chloride ions instruct muscles to relax. However, in myotonia congenita, the chloride ion channel malfunctions, disrupting this balance. As a result, muscle cells end up with too much sodium and not enough chloride, causing abnormal repetitive electrical signals, like those triggered by fear, to result in stiffness.

Although fainting goats often steal the spotlight, myotonia congenita also affects other animals, ranging from mice to humans.

This condition is hereditary and can be passed down as either a dominant trait (where only one parent needs to pass on the gene) or a recessive trait (where both parents must carry the gene). What sets fainting goats apart from other myotonic animals is that they are intentionally bred to enhance myotonia congenita in their offspring.

Some people with the disorder manage their symptoms through medication or physical therapy, while many miniature schnauzer breeders use genetic screening to prevent the birth of myotonic puppies. In contrast, fainting goats are specifically bred and raised to experience these episodes, with the goal of encouraging them to stiffen and collapse.

While fainting goats are selectively bred to encourage myotonia congenita, there are ethical concerns surrounding this practice. Breeders often assert that the goats do not suffer any pain during the fainting episodes, as the condition does not cause discomfort.

However, Kathy Guillermo, Director of Research for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), notes that fainting goats provide little to no benefit according to her organization’s perspective.

On the other hand, the Humane Society doesn’t view the issue with the same severity.

Jordan Crump, a representative of the Humane Society, explained that any concerns about their selective breeding are minor when compared to the serious issues found in the meat and poultry industries. He also suggested that the novelty of fainting goats likely ensures that most of them receive better care than typical farm goats.

Currently, neither the Humane Society of the United States nor PETA has taken an official stance on this specific matter.

Reasons to Breed Fainting Goats

Goats are known for their love of jumping and climbing, which makes fencing them in a challenge. However, when fainting goats attempt to jump or climb, they simply collapse instead.

Goats are known for their love of jumping and climbing, which makes fencing them in a challenge. However, when fainting goats attempt to jump or climb, they simply collapse instead.While myotonia congenita naturally occurs as part of an animal's genetic makeup, fainting goats exist as a breed solely because of human preference for them.

An animal with myotonia congenita would have a tough time surviving in the wild. If a predator approached, the animal would freeze, collapse, and become an easy target for natural selection. Only the strongest would survive, and the weaker ones would perish — that is, unless human breeders step in to protect and preserve those traits. This is an example of unnatural selection, a concept seen in many domestic and farm animal breeding programs.

Though myotonia congenita likely predates recorded history, the intentional breeding of this trait in goats, leading to the development of fainting goats as a distinct breed, began in the early 1880s in Marshall County, Tennessee. Some sources trace the breed's origins to a farmer named John Tinsley, who reportedly brought a group of goats exhibiting symptoms of myotonia congenita from Nova Scotia, Canada. These goats were bred by a local doctor, and over 120 years later, fainting goats are now found in herds across the United States.

But what is it about this breed that has made it thrive?

Throughout history, humans have selectively bred animals for two primary purposes: to enhance specific behavioral traits and/or to promote certain physical characteristics.

For instance, a guard dog might be bred for its aggression, while toy and show dogs are often bred for their appearance. Whether the goal is for entertainment or to fulfill a particular function, there is always an underlying reason for the direction of unnatural selection.

Fainting goats, like many other breeds, have been selectively bred for three main purposes:

- For meat: Fainting goats, like most farm goats, are often raised for slaughter. Goats are known for their natural ability to climb and jump, making them escape artists when confined. Farmers often have to put in extra effort to keep them enclosed. However, myotonia congenita reduces their tendency to climb and jump since these actions can trigger fainting. Moreover, the muscle tensing that occurs tends to increase muscle mass, decrease body fat, and result in a higher meat-to-bone ratio compared to other goat breeds.

- For amusement: Fainting goats are sometimes raised as pets for their unique fainting behavior, and in some cases, because they are easier to manage in an enclosure. Their calm temperament and distinctive appearance also make them good companion animals, much like other goat breeds.

- To accompany herds: Fainting goats were historically considered useful for protecting sheep herds. When frightened, they would either freeze or fall over, making them an ideal decoy for predators. In the event of an attack, the non-myotonic sheep would run away, leaving the fainting goats behind, either immobilized or limping due to the fear. The predators would then focus on the easier target. This practice, however, has mostly fallen out of use, and the extent of its historical use remains unclear.

Whether raised for food or as pets, fainting goats are here to stay. With an estimated population of 3,000 to 5,000, they are officially recognized as a breed and raised across the United States. Enthusiasts have even established breed standards and regularly showcase their prized goats at livestock shows.

Fainting goats serve multiple purposes: as a source of food, for entertainment, and as a means of protecting herds.

David Silverman/Staff/Getty Images

Fainting goats serve multiple purposes: as a source of food, for entertainment, and as a means of protecting herds.

David Silverman/Staff/Getty Images