In 1995, Fox approached Ted Koppel, an Emmy and Peabody award-winning news anchor, with an unusual request: to portray Alfred E. Neuman, the iconic fool from Mad magazine, in their upcoming late-night sketch comedy show, Mad TV.

“We’d be thrilled to have Ted join us anytime,” stated Fax Bahr, co-creator of Mad TV. “Aside from David Letterman, he’s the closest match to Alfred E. Neuman.”

While it’s unlikely the seasoned broadcaster would have accepted the offer, no matter how complimentary, that wasn’t the main focus. The irreverent tone was a cornerstone of Mad TV (sometimes written as MADtv), which boldly aimed to challenge the sketch comedy titan, Saturday Night Live.

In any other year, such ambition might have appeared hopeless. However, in 1995, SNL was grappling with harsh criticism, falling viewership, and a complete reshuffle of its cast and crew. Celebrating its 20th anniversary, the show seemed vulnerable to Fox executives, who saw an opportunity to dethrone it using another comedy legend—the gap-toothed fool, Alfred E. Neuman.

What the creators of Mad TV didn’t foresee was Fox’s relentless efforts to undermine them at every step.

The Usual Gang of Idiots

Throughout the 20th century, Mad stood as a cornerstone of American satire. Launched in 1952 as a comic book, it transitioned to a magazine format to evade censorship in the comic industry. Under the guidance of creator Harvey Kurzman and his editorial team, the publication humorously targeted pop culture, advertising, and politics. Their bold satire sometimes drew the attention of authorities, such as when the Treasury Department investigated their fake $3 bills featuring Alfred E. Neuman’s face in 1967. (The FBI, already monitoring Mad’s countercultural humor, could have provided a reference.)

Efforts to expand the Mad brand often fell flat. A 1974 animated TV special never made it to air. The 1980 film Up the Academy, directed by Robert Downey Sr., was meant to be a Mad-branded project akin to the National Lampoon movies. However, the final product was so poor that Mad publisher William Gaines withdrew the Mad endorsement, though a character in the film still dons a Neuman mask.

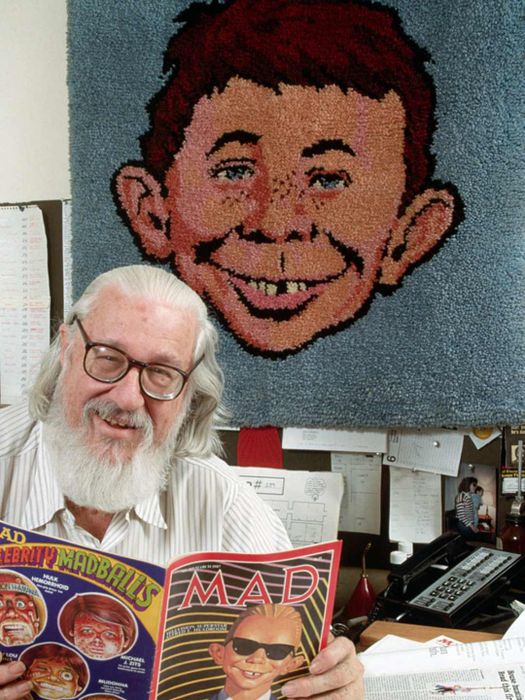

William Gaines. | Cheryl Chenet/GettyImages

William Gaines. | Cheryl Chenet/GettyImagesGaines, who previously managed EC’s controversial horror comics, was hesitant to relinquish control to external partners. He refused paid advertisements in the magazine, fearing they would influence its content, and avoided television adaptations of Mad due to his general disdain for the medium.

Years later, an aging Gaines met with producer David Salzman and his associate Steven Haft, who sought to license the Mad brand for a sketch comedy series. While it’s unclear if Gaines personally approved, his estate granted permission after his death in 1992. The agreement was likely facilitated by Mad being a Time Warner asset at the time, and Salzman’s QDE company, co-owned with music producer Quincy Jones, had strong ties to the entertainment conglomerate. (Jones would later serve as an executive producer for the show.)

Salzman, however, didn’t aim to replicate Mad verbatim. While key elements like Neuman and Spy vs. Spy were retained, much of the magazine’s imagery was limited to promotional materials or transitional segments in the show.

“We’re not trying to directly adapt the magazine for television because it wouldn’t work,” Salzman explained. “The magazine has a timeless, proven formula that appeals to younger men and older boys. Our TV show, however, targets a broader audience of men and women. It needs to feel contemporary, relevant, and distinctly ’90s.”

To avoid mimicking SNL, Salzman brought in Fax Bahr and Adam Small, veterans of In Living Color, to reimagine Mad for TV. Unlike SNL, which focused on timely topics and its Weekend Update segment, Mad TV would lean into timeless cultural references. Episodes often featured parodies like a Star Trek skit rather than current events like the Unabomber.

Salzman noted that assembling the Mad TV cast was like “building a sports team from the ground up.” The ensemble, including Bryan Callen, Artie Lange, Nicole Sullivan, David Herman, Mary Scheer, Phil LaMarr, Debra Wilson, and Orlando Jones, brought a diverse mix of stage, stand-up, and acting talent—arguably more varied than SNL’s lineup.

This effort was aided by SNL’s own struggles, as it had recently overhauled its cast and writing staff after the 1994–1995 season, introducing new faces like Will Ferrell and Cheri Oteri.

“The cast has grown too large,” remarked Don Ohlmeyer, NBC’s West Coast President. “No standout characters have emerged in the past few years. It’s time to refresh the writing team and bring in new talent. These are issues Lorne [Michaels, SNL creator] is well aware of and actively addressing.”

In the realm of televised sketch comedy, SNL appeared vulnerable, and Fox aimed to capitalize on this. “We believed it was the perfect opportunity to aggressively compete,” stated Fox President John Matoian. After reviewing a pilot of Mad TV, the network greenlit 12 additional episodes.

Mad TV enjoyed a significant advantage during its October 14, 1995, premiere: SNL aired a best-of compilation that night instead of a new episode. The ratings revealed that Mad TV dominated the 11 p.m. to 12 a.m. slot, outperforming SNL in 33 markets. Memorable sketches like “Gump Fiction,” which reimagined the gentle Forrest Gump in a Tarantino-esque setting, generated buzz, as did a cameo by Kato Kaelin, a figure linked to the O.J. Simpson trial.

Fox had reason to celebrate, especially as ratings stayed robust in the following weeks. Although SNL often led with a 5.5 rating (about 5.5 million households) compared to Mad TV’s 4.1, the latter occasionally matched SNL in the prized 18–49 demographic. However, by spring, Mad TV faced competition from Fox’s search for new Saturday night programming.

Hello, Neuman

While Mad TV was being produced, Fox commissioned Saturday Night Special, a variety series with rotating hosts, produced by Roseanne Barr. In spring 1996, Fox interrupted Mad TV to air six consecutive episodes of Saturday Night Special, signaling potential doubts about the sketch show’s future.

Fox executives made their stance clear. “If Roseanne’s show performs well and Mad TV fails, we’ll replace Mad TV,” Matoian stated.

The results showed a clear preference for Mad TV. Fox ordered 25 episodes for the 1996–’97 season, while Barr’s show was not renewed. However, this decision highlighted an ongoing tension between Mad TV’s team and Fox: the belief that the network lacked commitment to the show. Promotion was scarce, budgets were cut, and sketches were extended to maximize resources.

“After decades in the industry, I thought I’d seen it all,” Salzman remarked. “But this has been a unique challenge. We’ve never gotten a fair shot. If anything, we’ve faced constant obstacles… it’s astonishing how overlooked we’ve been.”

Nicole Sullivan shared Salzman’s sentiment, though less tactfully. “I’m not going to sugarcoat it,” she said. “We’re treated like the unwanted stepchildren of the network. They ignore us. We simply don’t matter to them.”

Fox executives acknowledged this, pointing to the show’s budget-to-revenue ratio as a reason for the lack of promotion. “Mad TV will always feel like the stepchild because it’s the only non-primetime show [on Fox],” David Nevins, executive vice-president of programming, said in 2001.

Meanwhile, SNL was undergoing another revival, with performers like Ferrell, Oteri, and others connecting strongly with audiences. Critics often noted that characters such as Ferrell and Oteri’s cheerleaders were overused, but this was typical in sketch comedy. On Mad TV, recurring characters like Michael McDonald’s Stuart Larkin, a needy man-child, and Alex Borstein’s Ms. Swan, introduced in 1997, were fan favorites, though the latter faced criticism for reinforcing Asian stereotypes. Borstein clarified that Swan was inspired by her Hungarian-Mongolian grandmother.

Mad TV also faced backlash for its biting parodies, which sometimes upset the celebrities being mocked. Rosie O’Donnell was offended by a sketch depicting her as a sexual predator, while Drew Barrymore and Britney Spears reportedly found their portrayals irritating. Nicole Sullivan recalled in 2016 that Spears’ bodyguard once “very obviously shoved me several feet away from her.”

Goodbye, Neuman

Despite Fox’s lukewarm support, Mad TV steadily grew its audience in the early 2000s. “Early on, our audiences included Marines on group outings and rehab patients just happy to be out,” Phil LaMarr noted in 1999. “Now, we have fans who know the show, recognize the characters, and cheer without needing cues. It’s a real testament to the show’s impact.”

The show continued to showcase talent, with Keegan Michael-Key and Jordan Peele joining in its ninth season before creating their acclaimed sketch series, Key and Peele.

Despite its efforts, the series couldn’t shake its reputation as a secondary priority, and by 2008, Fox ceased funding entirely. Mad TV was canceled after 14 seasons.

The CW attempted a short-lived revival in 2016, featuring a few original cast members as guests, but it lasted only one season. Shortly after, Mad magazine halted its print edition, further eroding the brand’s prominence. (It has since resumed publishing new content.) However, just as Mad’s impact on American comedy is undeniable, so is Mad TV’s achievement: it survived for over a decade against the comedy giant SNL, which is now approaching its 50th season.

Critics noted the mutual influence between the two shows. Mad TV eventually incorporated more guest stars, while SNL increased its use of animated segments like The Ambiguously Gay Duo, inspired by Mad TV’s popular holiday specials, including a mafia-themed Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer parody.

Lorne Michaels, creator and producer of SNL, rarely discussed Mad TV but shared his thoughts in 1999. He concluded that Mad TV wasn’t truly a competitor. “They’ve always positioned themselves as superior to Saturday Night Live, fresher than Saturday Night Live,” he said. “That’s how they’ve been evaluated, which is unfortunate because they can stand on their own. The shows are compared because they air at the same time, but they’re not alike. Mad TV focuses on parody, while we’re more of a live variety show.”

Ted Koppel never appeared on Mad TV—instead, the show held an Alfred E. Neuman lookalike contest for its premiere. However, a version of Koppel did make it to the screen: Frank Caliendo portrayed him in a 2002 episode.