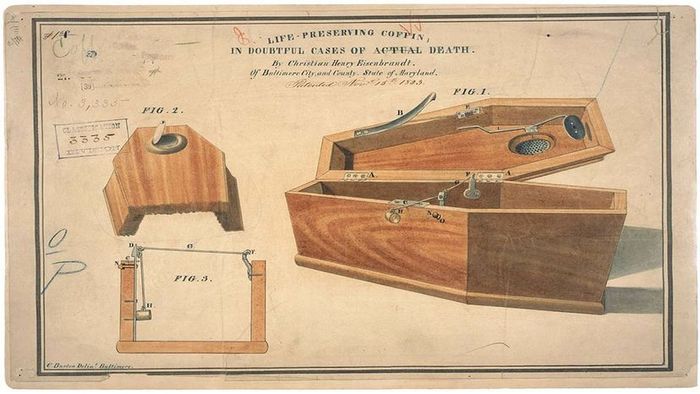

The printed patent illustration from 1843 showcases Christian H. Eisenbrandt's innovative life-preserving coffin. Designed with a spring-loaded mechanism, the lid would instantly open upon detecting even the smallest movement of the head or hand. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

The printed patent illustration from 1843 showcases Christian H. Eisenbrandt's innovative life-preserving coffin. Designed with a spring-loaded mechanism, the lid would instantly open upon detecting even the smallest movement of the head or hand. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.As George Washington lay on his deathbed in 1799, he called for his secretary, Tobias Lear, and uttered in a faint, strained voice, "I am about to depart. Ensure I am buried properly, and do not place my body in the Vault until at least three days have passed since my death."

These were Washington's last words, a cautious directive from a man unafraid of death itself but, like many in his time, deeply fearful of the horrifying possibility of premature burial.

During Washington's era and much of the 19th century, the fear of premature burial was a genuine concern. Medical knowledge was rudimentary, and death could result from everyday ailments, infected injuries, or rapid smallpox epidemics. With mortality rates high and scientific advancements scarce—even basic tools like stethoscopes didn't emerge until the 1820s—it was widely believed that many individuals were interred before they were truly deceased.

The intense dread of being buried alive, known as taphephobia (from the Greek word 'taphe' meaning burial), was part of a broader fascination with death that captivated the Western world in the 1800s. This fear led to the creation of 'safety coffins' (also called 'security coffins'), ingeniously designed caskets that allowed those mistakenly buried to free themselves from their graves.

Frankenstein, Seances and the 'Gray Area' of Death

According to Adam Bisno, a historian at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the first patents for security coffins emerged in the 1790s in central Europe. This timing aligns with the rise of German Romanticism, which deeply influenced European intellectuals of the period.

Romanticism arose as a reaction to the Enlightenment's focus on logic and reason. Instead, Romantic thinkers pursued truth in the 'unseen and unknown,' as Bisno explains, exploring ambiguous realms such as the uncertain boundary between life and death.

In 1818, Mary Shelley released "Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus," a novel that mirrored the 19th-century obsession with the thin boundary separating life and death. By the mid-1800s, seances and mediums became popular, offering methods for the living to connect with the deceased, who appeared to inhabit a realm just beyond our own.

"People were questioning, 'Are the dead truly gone? Do they still linger among us?'" explains Bisno. "The fear of being buried alive resonated deeply with this curiosity. It represents someone beneath the ground who is both present and absent, alive yet not alive, dead but somehow not entirely gone."

The Patent Craze of Life-preserving Coffins

According to Bisno, over 100 patents for security coffins were issued in America by the USPTO during the 19th century, with each new design boasting more elaborate features than its predecessor. (Each Halloween, the USPTO highlights eerie and morbid patents in its Creepy IP series.)

One of the earliest U.S. patents for a 'life-preserving coffin' (an ironic term?) was submitted in 1843 by Christian H. Eisenbrandt of Baltimore, Maryland. His design included a spring-loaded lid that would open instantly with the slightest movement of the head or hand. To ensure functionality, Eisenbrandt proposed placing the coffin in an above-ground vault, with the vault door key left inside, "so that if the person isn't truly deceased, their life may be saved."

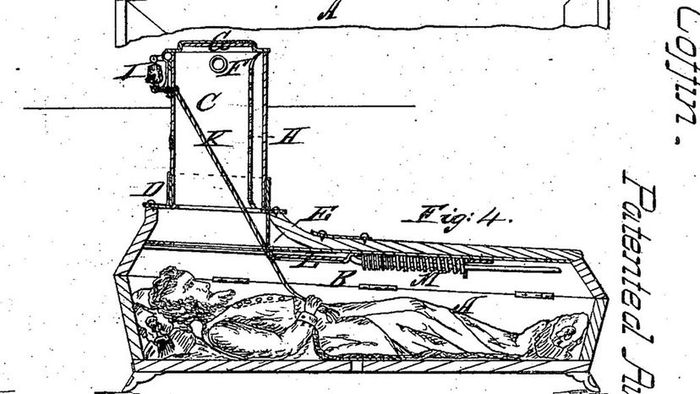

This illustration depicts Franz Vester's 'improved burial-case,' U.S. Patent No. 81,437, granted on August 25, 1868, in Newark, New Jersey.

Wikipedia

This illustration depicts Franz Vester's 'improved burial-case,' U.S. Patent No. 81,437, granted on August 25, 1868, in Newark, New Jersey.

WikipediaHistorians uncovered advertisements from 1844 promoting Eisenbrandt's jack-in-the-box coffin, capitalizing on the widespread (yet baseless) fear of the 'frequency and peril' of premature burial and the need for such a contraption. While it's unclear how many were produced, sales may have been bolstered by Edgar Allen Poe, who released his chilling tale "The Premature Burial" that same year.

"Being buried alive is, without doubt, the most horrifying fate that can befall a mortal," Poe wrote, delving into the macabre themes of Romanticism. "That it has occurred often, very often, will hardly be disputed by those who ponder such matters. The line separating Life from Death is faint and ambiguous. Who can determine where one ends and the other begins?"

In 1868, Franz Vester of Newark, New Jersey, patented his 'improved burial-case,' which included a narrow tube with a ladder, enabling a revived person to climb to safety. If the individual was too feeble to escape alone, they could tug a rope inside the coffin, triggering a bell above ground to signal for help.

Vester showcased his coffin in public demonstrations, such as one documented by a New York Times reporter in 1868. During the event, he was buried under four feet of soil and reemerged an hour later, climbing out of his 'living grave' to the cheers and applause of the onlookers.

The 'Count' of Security Coffins

The most flamboyant figure in the 19th-century security coffin scene was Count Michel de Karnice-Karnicki, who claimed to be a 'chamberlain to the czar of Russia.' He traveled across Europe and the United States, showcasing his ingenious coffin device, which he named 'Le Karnice.'

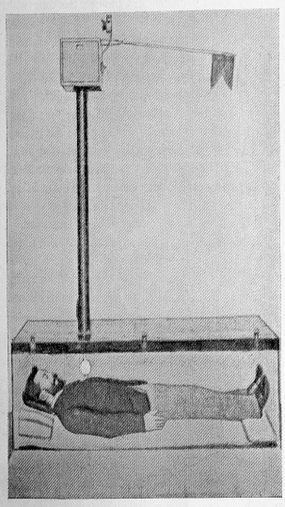

Count Karnice-Karnicki's creation featured a mechanism that would activate upon movement by the 'corpse,' releasing light and oxygen into the coffin.

Wikimedia

Count Karnice-Karnicki's creation featured a mechanism that would activate upon movement by the 'corpse,' releasing light and oxygen into the coffin.

WikimediaIn a 1899 newspaper article, The Chicago Tribune covered a meeting of the Academy of Medicine in New York City, where Dr. Henry J. Garrigues shocked attendees by claiming that one in every 200 people buried in the U.S. was actually in a 'lethargic state' and buried alive.

This dubious statement set the stage for Count Karnice-Karnicki, who showcased his invention. Le Karnice enhanced existing security coffins by activating alarms and alerts with any bodily movement. It included a ringing bell and a rising shiny ball. The trapped person could breathe and communicate through a specialized tube while awaiting rescue.

To prove its efficacy, the Count invited volunteers to be buried alive. The world record for the longest voluntary live burial still belongs to Faroppo Lorenzo, an Italian man who spent nine days in Le Karnice in 1898.

Despite the theatrical displays, Bisno is convinced the Count never mass-produced Le Karnice. "No one purchased it," Bisno explains. "Funeral directors and the public showed no interest. In reality, none of these inventions gained traction."

A significant flaw in safety coffins is the unsettling reality that corpses do move, albeit involuntarily. As decomposition occurs, a body can shift or even turn over, potentially setting off false alarms in most security coffin designs.

Though not a traditional security coffin, a unique grave in New Haven, Connecticut, features a window. Dr. Timothy Clark Smith, who passed away in 1893, was so terrified of premature burial that he built an elaborate underground tomb. His body was placed alongside a hammer and chisel, and the window enabled cemetery staff and visitors to verify if Smith had revived. So far, no activity has been reported.