Dina Zirlott and her daughter, Zoe, in 2007.

Warning: This story discusses sexual assault and suicidal ideation.

At 17, I was sexually assaulted. By 18, I had given birth to a child. By 19, that child had passed away.

The details of the day I was assaulted are hazy — I can’t recall the sky’s color or the events leading up to it. My life is now divided into Before and After, with me stuck in the middle.

What I do remember: A boy from school, someone I considered a friend, came over to watch a movie. His hand moved up my leg, and when I asked him to stop, he simply said, “I don’t want to.” I thought leaving the room would calm things down, so I went to the kitchen for water.

I remember: Him trapping me against the kitchen counter, knocking the air out of me. His hand covered my mouth, then gripped my throat. The sound of fabric tearing, the counter digging into my stomach, my hands slipping on the granite. Time seemed endless. I fought back, tried to escape, but a strangled cry escaped me as his grip tightened. I stopped resisting. I felt detached, as if I were watching my body from afar — it was no longer mine.

I don’t remember him leaving. I vaguely recall cleaning blood off the kitchen floor. My mind was in survival mode, unable to process what had happened. I didn’t think to keep my clothes, wake my mother, or call the police. I lay in bed, unable to comfort myself, even with my own touch. I thought about drowning myself in the pool, imagining sinking to the bottom and letting go.

Before the assault, I was an honor student, a cheerleader, and a choir member. I had dreams and plans. But within months, my grades dropped, I quit cheerleading, and I became sick and withdrawn. I lost weight and was consumed by suicidal thoughts.

Attempting to feed Zoe during her first evening at home.

In the After, nearly eight months later, my mother discovered a book about recovering from rape hidden under my bed, wrapped in newspaper. She broke down, apologizing and listing all the signs she had missed over the past months. Her guilt and worry felt like a heavy, smothering weight. At that time, I couldn’t accept love. I felt my body was tainted.

Just when I thought things couldn’t get worse, my mother took me to her gynecologist for STI and pregnancy tests. Only the pregnancy test was positive. In the months following the assault, my mental state had deteriorated so severely that I hadn’t considered my illness might have a cause. I was weak, my stomach barely showing, and my periods had always been irregular. I felt like poison — how could anything grow inside me?

The nurse avoided eye contact and checked a box on my chart. “Do you know who the father is?” she asked flatly.

“I was raped,” I replied, watching her pen pause mid-air.

My mother accompanied me to the ultrasound. I was terrified to look at the screen, fearing undeniable proof. The technician asked if I wanted to know the gender. I must have agreed, because she patted my arm and said, “It’s a girl.”

She fell silent after that. As she scanned the head and took measurements, her expression darkened. After cleaning my stomach, she led us to a conference room. My mother fidgeted nervously, while I stared at the chair across from me. We both sensed something awful was coming.

The doctor laid out the ultrasound images and pointed to dark areas where brain matter should have been. She explained it was hydranencephaly, a condition where the brain’s hemispheres fail to develop, replaced by cerebrospinal fluid. The fetus’s brain stem allowed some development, but she would be born blind, deaf, cognitively impaired, and prone to seizures, diabetes insipidus, insomnia, hypothermia, and more. The list of her potential suffering was overwhelming.

“This condition is not compatible with life,” the doctor said, her tone detached, as if observing a tragedy from afar.

A short, painful existence. I blamed myself, convinced I had caused this. No one could persuade me otherwise. I was both victim and perpetrator, powerless in both roles.

My mother asked about our options, but I was already eight months pregnant. Abortions in Alabama were only allowed “up to the stage of fetal viability, usually between 24 and 26 weeks gestation.” It was too late for me. Even if I sought a “late-term abortion” out of state, I’d face time, paperwork, politics, and financial barriers.

“I wish I could do more,” the doctor said. “I know how unfair this must feel.”

The words “cruel” and “inhumane” echoed in my mind. I had already endured one trauma — wasn’t that enough? I was barely holding on, desperate for normalcy, yet more was being ripped away from me.

I dropped out of school during my senior year. My rapist seemed to haunt the halls, even when he wasn’t there. My parents asked if I wanted to report him, but I couldn’t face reliving that night in front of strangers. I wasn’t strong enough for the courtroom’s scrutiny. Shame, depression, anxiety, anger, and grief consumed me.

My daughter, Zoe Lily, was born on Oct. 27, 2005. At first, I couldn’t bring myself to hold her, fearing I’d hurt her further. I was terrified she’d die in my arms or that I’d feel the same disgust for her as I did for myself. They took her away, and the neurologist asked how we wanted to proceed. He explained her brainstem controlled only the most basic functions and suggested making her comfortable rather than prolonging her suffering.

I curled up in the maternity ward, an 18-year-old retraumatized by the attack, paralyzed by indecision. When my milk came in, it felt like a cruel joke. I couldn’t imagine then how my love for her would grow over the next year, even as I wished she had never been born.

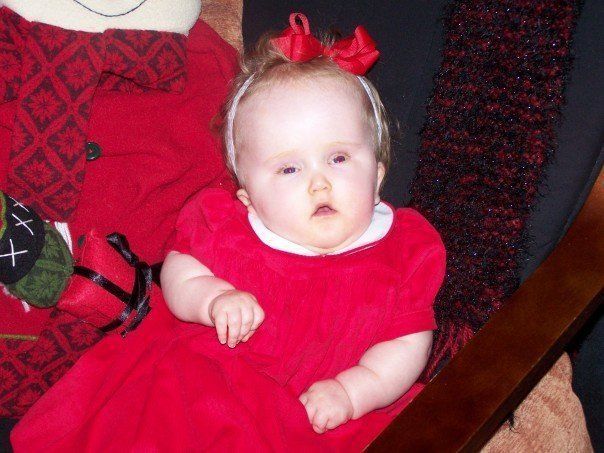

Zoe during Christmas, prior to our hospital admission.

We brought Zoe home, fully aware she would pass away there. For a year, my family poured love into her.

We learned to feed her using a bottle by gently lifting her chin until she latched onto the nipple. Each feeding took two hours. We held her through endless nights, as her body couldn’t process sleep hormones. She would stiffen during seizures, her blue eyes jerking to one side. I’d cradle her, breathing in her soft scent, trying to etch it into memory. Sometimes, I wished her heart would stop, freeing her from pain. I both prayed for and feared that moment.

Even in the Alabama summer, we wrapped her in electric blankets because she couldn’t regulate her temperature. Every major holiday that year was spent in the hospital. On Thanksgiving, her lips turned blue, and she stopped eating due to a kidney infection. The antibiotics nearly took her life.

On Christmas, we watched as nurses struggled to place IVs, her veins collapsing one by one. She was on a cocktail of medications: Zantac, anti-diuretics, Synthroid, Klonopin, lorazepam, melatonin, and Miralax. She was diagnosed with diabetes insipidus. We hung red stockings by her hospital bed, listening to the steady beep of her heart monitor.

Amid all this, I started college at a local university. I juggled classes with Zoe’s doctor appointments, trading shifts with my mother so she could work. I enrolled in the nursing program, as it seemed practical given our circumstances. I made one friend, who later became my husband. My life felt chaotic, but I clung to a fragile sense of control.

On Easter, we were back in the hospital with a urinary tract infection, proteinuria, and an uncontrollable fever. The pediatrician warned us to prepare for the end. We took her home once she stabilized.

Unlike the day of my assault, I remember Zoe’s death with painful clarity.

She had seizures all night. Though common, my mother and I decided to take her to the ER at dawn. I got dressed, but my mother suggested I wait until after my 8 a.m. class. It was midterm week, and we agreed I shouldn’t skip. I kissed Zoe’s cheek before leaving.

While emailing my English professor about a family emergency, my mother stopped answering her phone. A part of me thought, Maybe this is it, and I felt a terrible relief.

Losing a child is unimaginable, even when expected. My best friend arrived at my house. “We need to go to the hospital. Zoe just died.” I collapsed, sobbing on the floor, detached from my body. I fixated on a dead moth on the windowsill, the sun streaming through the glass.

Her heart had stopped. She died in my stepfather’s arms. I couldn’t bring myself to look at her. I felt hollow.

At home, we packed away her belongings. Holding her pajamas, I felt an overwhelming emptiness. I longed to put socks on her tiny feet one last time, to kiss her hands. We buried her with the blankets she loved. I wanted to lie beside her, for it all to end. How could I go on? A black hole seemed to open inside me, devouring everything good and tender, leaving nothing of who I once was.

Even now, the grief consumes me. It has no teeth, yet it swallows me whole. In the 12 years since her death, it has derailed me countless times. I am fragmented. Part of me is still wiping blood from white tiles. I am the dead moth on the sill. I am buried under layers of dirt. And I am here, in these words. I am vast.

I now have three daughters, and I love them fiercely. But I grieve what was taken from me—the person I might have been if not for the assault, the motherhood forced upon me, the traumas that followed. Did that girl not deserve mercy? Was her life less valuable?

It shouldn’t have been this way.

If I had been allowed a “late-term abortion,” would I have chosen it?

Yes. A hundred times over, yes. It would have been a kindness. Zoe wouldn’t have suffered so much in her short life. Her heart could have stopped while she was warm and safe inside me, sparing her the pain that followed.

Perhaps I could have been spared, too.

Dina Zirlott in 2018, alongside her husband, Lance, and their daughters, Aine (7), Ariadne (5), and Asher (3).

I’ve witnessed the #MeToo Movement amplify women’s voices. I’ve seen the venom directed at sexual assault survivors and women who’ve faced the heart-wrenching choice of abortion. Now, I watch as our bodies are politicized and exploited. Judging without understanding is the height of cowardice. I challenge you to sit with me, hear my story in my own words, and tell me to my face how I should feel or what I should have done. Claim you understand my pain better than I do. Tell me it doesn’t matter.

Why am I sharing this? You might think I seek attention, and perhaps I do, in a way. After 12 years of carrying this burden in silence, I’m exhausted. The constant suppression, the silent suffering—it wears you down.

Why should I remain silent when my words can reach farther than my hands ever could?

Look at the photo of me and my daughter and tell me you know better than I do.

Listen to me. I am a human being, more than just a vessel. I speak for my daughter, who never cried. I speak for the 17-year-old girl bent over a kitchen counter. I speak for the woman I’ve become. And I speak for all women like me, past and future, who’ve faced or will face similar struggles—or perhaps your story is entirely different but equally powerful.

These are our bodies, our lives. Rarely do we choose the circumstances that force such heavy decisions, but these choices are ours. We shouldn’t have to beg for the right to decide what’s best for ourselves and our children, even those who may never be born—or perhaps never should be born.

Dina Zirlott is a 31-year-old stay-at-home mom living in Mobile, Alabama, with her husband and three daughters. In her free time, she enjoys baking and decorating cakes, though her skills—and taste—are questionable.

Need help? Visit RAINN’s National Sexual Assault Online Hotline or the National Sexual Violence Resource Center’s website.

If you or someone you know needs help, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. You can also text HOME to 741-741 for free, 24-hour support from the Crisis Text Line. Outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention for a database of resources.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost in 2019 and was updated in 2021.