According to Reebok president Paul Fireman, the company's primary challenge boiled down to a single issue: Michael Jordan had gas.

In 1988, Nike's Air sneakers, endorsed by Jordan, featured a gas-filled heel cushion for enhanced comfort and support. This innovative blend of science and footwear, paired with Jordan's star power, allowed Nike to rapidly gain market dominance. By the next year, Nike had surpassed Reebok in sales.

Fireman knew action was necessary. He assigned engineer Paul Litchfield to lead the development of a customizable sneaker, offering only Ellesse's inflatable ski boot as inspiration—a bulky, outdated design with brass fittings, far from ideal for athletic use.

Within a year, Litchfield and his team transformed a rudimentary concept into a game-changing innovation, generating nearly $1 billion in sales. Their journey included a banned TV commercial, bold ads targeting Jordan, and intense legal battles. The Reebok Pump's success was so overwhelming that it threatened to outgrow the company itself.

The bladder integrated into every Pump. Reebok

Running enthusiast Joseph William Foster’s vision for spiked racing shoes inspired the creation of J.W. Foster and Sons in 1895. Decades later, in 1958, his descendants discovered a dictionary from South Africa, a prize from one of his races. It featured the word rhebok, an antelope native to the region, but misspelled as reebok. The family embraced the name, making it their own.

Sneaker branding gained widespread attention in 1968 when athletes sported striped Adidas during the first globally televised Olympics. Reebok rose to prominence a decade later with its aerobic-focused footwear. The Reebok Freestyle, promoted by fitness expert Gin Miller, became a sensation, capturing half of all women’s sneaker sales in the U.S. at its peak.

Reebok's dominance waned after 1987, culminating in Nike overtaking them in 1989. Founded by Phil Knight, Nike aligned itself with Michael Jordan during a surge in athlete endorsements. Even in ads for McDonald’s, Jordan’s connection to Nike was unmistakable. The slogan "Just Do It" became ingrained in popular culture, solidifying Nike's place in the market.

Falling behind motivated Fireman to accelerate innovation, but Reebok lacked sufficient design resources. Tasked with creating a customizable sneaker, Litchfield collaborated with Design Continuum, a Massachusetts consultancy known for turning abstract ideas into reality. One designer had prior experience with inflatable splints, while another had worked on intravenous bags. Combining these insights led to the breakthrough: an inflatable bladder integrated directly into the shoe.

Design Continuum delivered a concept akin to an advanced blood pressure cuff. Inflating the bladder would expand the sneaker, offering superior ankle support—though Reebok avoided claiming it could reduce injuries.

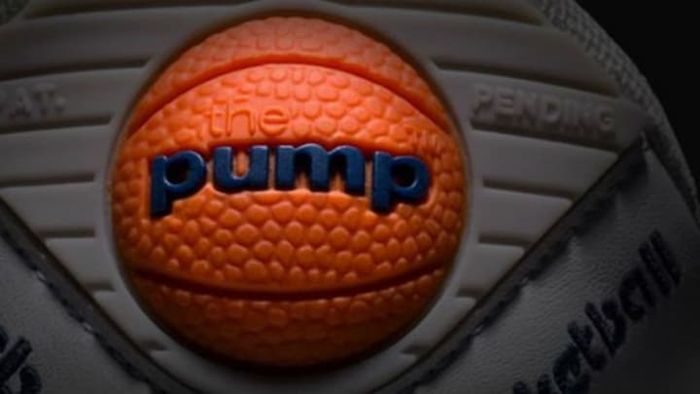

Two prototypes were created: one with manual inflation and another that inflated automatically as the wearer walked. Litchfield found the automatic version intriguing, almost as if the shoe had a life of its own, but high school tests revealed kids preferred the manual pump. The playful hiss of releasing air added to the appeal, making the Pump feel like a toy. Designer Paul Brown enhanced this by shaping the inflation mechanism like a basketball.

Retrobok

At its February 1989 trade show debut, the shoe drew significant attention, but Litchfield felt uneasy. Nearby, Nike showcased the Air Pressure, a competing air-chambered sneaker, in a private display, signaling a looming rivalry.

Litchfield feared Reebok might miss its moment, but the Air Pressure had a critical weakness: it relied on an external pump to inflate the shoe. As Nike discovered, consumers weren’t interested in carrying extra equipment for their sneakers.

Despite Nike’s apparent advantage, Fireman was determined to act quickly. Encouraged by the trade show response, he instructed Litchfield to launch the Pump by November that year. Though the timeline was tight, Litchfield believed it was achievable.

The Pump was revolutionary in athletic footwear. While the shoes were manufactured in Korea, the bladders were produced by a medical supply company in Massachusetts. This required Litchfield to test the bladders twice domestically, ship them overseas for assembly, and test them twice more to ensure no damage occurred during sewing.

Litchfield considered the process meticulous. However, when the first shipment of 7,000 pairs arrived in Boston that September, the warehouse called in a panic—none of the sneakers could inflate.

Cristian Borquez, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

The Korean factory had attempted to save time. To test the bladders post-assembly, they used sewing machines without needles, believing it would prevent damage. Instead, it warped the plastic molds. Litchfield and his team had to manually re-sew thousands of pairs with replacement bladders.

Despite Reebok's established reputation, the November 1989 Pump launch sparked significant debate. Priced at $170—a staggering amount at the time, even surpassing Nike's Jordan line—the sneaker's cost reflected the innovative bladder system. Reebok also recognized the potential appeal of a high price tag, as sneakers had become symbols of status and coolness in schools and on courts. If the Pump became a coveted item, consumers would prioritize it over other expenses.

Reebok's Pump debuted alongside Nike's inflatable sneaker, and consumer preference was clear. The Air Pressure, with its clunky design and detachable pump, couldn't compete. Reebok emphasized the Pump's custom fit, noting that one foot might need 16 pumps while the other required 21. Kids flocked to see the sneaker in action, even if they couldn't afford it.

NiceKicks

Reebok also took direct aim at Jordan, airing ads featuring Atlanta Hawk Dominique Wilkins mocking his rival: “Michael, my man,” he quipped, “if you want to fly first class, pump up and air out!”

Nike maintained a dignified stance, telling the press their shoes were designed for performance, not gimmicks. Reebok, however, pressed on. In March 1990, they aired a controversial TV ad during an NCAA game featuring two bungee jumpers. One jumper, wearing Pumps, returned safely with a smile, while the other, in ill-fitting Nikes, vanished, implying a fatal outcome.

Parents were outraged, calling the ad dark and inappropriate; CBS pulled it after one airing. Despite the backlash, the message hit its mark. By the close of 1990, Nike projected just $10 million in Air Pressure sales, while Reebok raked in $500 million from the Pump. The New York Times noted that if the Pump were a standalone company, it would rank as the industry's fourth-largest.

1990 was a landmark year for Reebok, but 1991 would surpass it. The Pump was poised to overshadow Jordan in his own backyard, and Reebok didn’t even orchestrate it.

Kickologists

Dee Brown, a rookie for the Boston Celtics, stood at six-foot-one, lacking the imposing stature of some competitors in the NBA’s 1992 slam dunk contest. Held in Charlotte, North Carolina, near Jordan’s hometown, the event would become a pivotal moment for the Pump.

After Jordan’s back-to-back wins in 1987 and 1988, he stepped aside, leaving hometown favorite Rex Chapman to dazzle the crowd. Dee Brown, waiting for his turn, decided to capture their focus. When he stepped onto the court, he crouched and pumped up his sneakers, electrifying the audience. Brown’s victory in the contest turned into an unforgettable promotional moment for the Reebok Pump, driving demand sky-high. Reebok’s sales surged by 26 percent in 1991.

The Pump quickly expanded beyond basketball. Tennis star Michael Chang endorsed a version with a fuzzy green tennis ball pump, while Boomer Esiason promoted it for football. Reebok introduced air-bladder designs for running shoes, golf shoes, and cleats, including models with digital displays and the Insta-Pump, which used a canister for instant inflation. The sneaker even appeared at the 1992 Olympics, a nod to its industry roots. By then, the top model was priced at a more accessible $130.

As the Pump’s popularity soared, competitors emerged. L.A. Gear, struggling with declining sales, released the Regulator, featuring air-bladder technology Reebok claimed infringed on their patent. The dispute ended with L.A. Gear paying Reebok $1 million and licensing fees to resolve the matter.

Design Continuum also posed an unexpected challenge, collaborating with Spalding on an inflatable baseball glove. Reebok, feeling betrayed, sued the firm for misusing trade secrets. The case was settled out of court, with details remaining confidential.

By 1992, when Shaquille O’Neal joined Reebok, six million Pumps had been sold. Reebok openly predicted a decline in Pump sales, viewing it as a springboard for future innovations. Fireman saw Reebok as a brand, not just a shoe company—a perspective that would later prove costly.

Reebok

Despite gaining 2 percent in market share after the Pump’s debut, Reebok couldn’t dethrone Nike. In 1992, Nike commanded 30 percent of the market, largely due to Jordan’s influence. Reebok’s gains came at the expense of weaker competitors like L.A. Gear and British Knights. By flooding the market with numerous Pump variations, they overloaded store shelves, causing the novelty to fade.

Nike’s focus on lightweight, performance-driven sneakers paid off: their designs became sleeker, while Reebok faced challenges with their bulky 22-ounce high-tops. Though Reebok didn’t collapse—achieving a record $3.8 billion in sales in 2004—they couldn’t catch up to Nike, which generated $12 billion in revenue that same year.

The Pump remained in production, available in modern and retro designs. In 2005, Reebok introduced a redesign developed with MIT and NASA engineers. Like Litchfield’s early prototype, it inflated automatically as the wearer walked. While the company released various iterations, none matched the success of the 1989 original.

This year, Reebok launched the ZPump Fusion, blending the comfort and fun of the bladder system with the streamlined look of cross-trainers. If it succeeds, Reebok may once again pull off one of the sneaker industry’s most ingenious moves: selling air and turning it into millions.