It’s often overlooked that before the rise of film, stage actors were icons in their own right, wielding power comparable to today's Hollywood A-listers. In 1880, Sarah Bernhardt earned $46,000 for just a month of performances during her first New York tour—a sum that would be worth over $1 million today. By 1895, English actor Henry Irving became the first actor ever knighted by the British crown. Back in 1849, a rivalry between two Shakespearean giants, William Macready and Edwin Forrest, sparked such fierce competition over their productions of Macbeth that their supporters rioted in the streets of Manhattan.

Yet, long before these figures, there was Ira Aldridge. Born in New York in 1807, Aldridge made an indelible mark on mid-19th century theater, earning prestigious accolades and becoming one of only 33 individuals honored with a bronze plaque at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. What makes Aldridge's story even more remarkable is the context of his time—an era rife with racial prejudice, where he, as a Black man, rose to unparalleled heights of acclaim.

Young, Gifted, and Black

Born to a minister and his wife, Aldridge was educated at New York’s African Free School, a program founded by the New York Manumission Society to serve the city's black community. His first exposure to theater likely came at Manhattan’s now-defunct Park Theatre, and soon he became captivated by the stage. While still a student, Aldridge made his acting debut at the African Grove Theatre, founded by free Black New Yorkers in 1821, performing in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s adaptation of Pizarro. Some accounts suggest that his Shakespearean debut followed soon after when he starred as Romeo in the African Grove’s production of Romeo & Juliet.

These early performances were met with success, as was the African Grove Theatre, which quickly gained fame as one of the few New York venues predominantly staffed by Black actors and attended mainly by Black audiences. However, despite these initial victories, both Aldridge and the theatre faced numerous challenges.

Not long after its opening, the Grove was shut down by city officials, allegedly due to noise complaints. The theatre was relocated to Bleecker Street, but this move distanced it from its core Black audience in central Manhattan and placed it closer to larger, more prestigious theaters. This shift led to increased competition, smaller audiences, and escalating financial troubles. The situation was further exacerbated by continuous harassment from the police, city authorities, and hostile local residents.

The situation eventually became untenable: the Grove shut its doors two years later and was reportedly destroyed by fire under mysterious circumstances in 1826. After enduring and witnessing racist abuse and discrimination in the U.S., Aldridge decided to leave. In 1824, he sailed for England, seeking a new future.

The African Tragedian

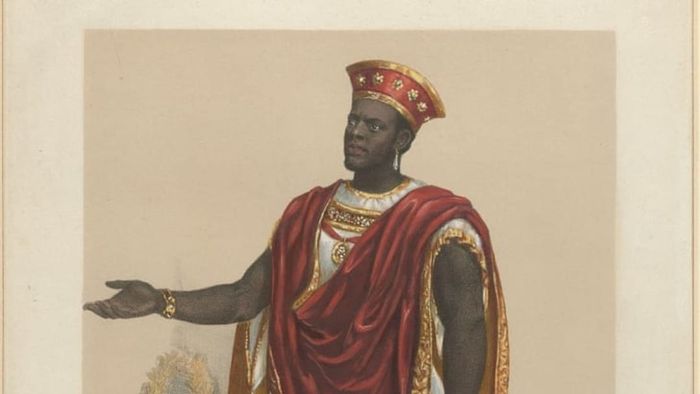

Ira Aldridge as Othello in 1854 | Houghton Library, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Ira Aldridge as Othello in 1854 | Houghton Library, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainBy this time, the British Empire had already abolished its slave trade, and the movement for emancipation was gaining momentum. Aldridge recognized that Britain presented a far more promising future for a young, ambitious Black actor like himself. What he couldn't foresee was how pivotal his transatlantic journey would become, shaping his destiny as much as his decision to leave America.

To fund his travel, Aldridge worked as a steward aboard the ship that took him to Britain. During the voyage, he had a chance encounter with British actor and producer James Wallack, whom he had met months earlier in New York. Wallack, recognizing Aldridge's potential, offered him a position as his personal attendant. Upon reaching Liverpool, Aldridge left his steward job and entered Wallack’s service, which allowed him to forge key connections in the theater world. By May 1825, Aldridge made his London debut, becoming the first Black actor in Britain to perform the role of Othello.

The critics, initially uncertain about a 'gentleman of colour lately arrived from America,' were ultimately captivated by Aldridge’s debut performance in Othello at the Royalty Theatre. They praised his 'fine natural feeling' and remarked that 'his death was certainly one of the finest physical representations of bodily anguish we ever witnessed.' Remarkably, Aldridge was only 17 years old at the time.

After making his debut in London at the Royalty Theatre, Aldridge gradually worked his way up the city's theatrical ranks, performing in increasingly prestigious venues. His portrayal of Othello moved to the Royal Coburg Theatre later in 1825. He then took on the lead role in a stage adaptation of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko, followed by an acclaimed supporting role in Titus Andronicus. To showcase his versatility, he also tackled a comedic role as a bumbling butler in the 18th-century comedy The Padlock. Aldridge’s reputation grew steadily, and he soon earned top billing as the 'African Roscius'—a nod to the famous Ancient Roman actor Quintus Roscius Gallus—or the 'African Tragedian,' becoming the first African-American actor to establish himself on the international stage.

Even in the more progressive society of abolitionist Britain, Aldridge faced significant challenges. When his performance of Othello moved to the prestigious Covent Garden in 1833, some critics found it intolerable to see a Black actor performing on one of London’s most revered stages. Their reviews turned harsh and revealing, with racism becoming ever more evident in their responses.

Campaigns were launched to remove Aldridge from the London stage, with the local Figaro newspaper among his most vehement adversaries. Shortly after his debut at Covent Garden, the paper began an open campaign to see him driven off the stage, calling for 'such a chastisement as must drive [Aldridge] from the stage… and force him to find [work] in the capacity of footman or street-sweeper, that level for which his colour appears to have rendered him peculiarly qualified.' Though the campaign ultimately failed, it tarnished Aldridge’s time on the London stage.

"The Greatest of All Actors"

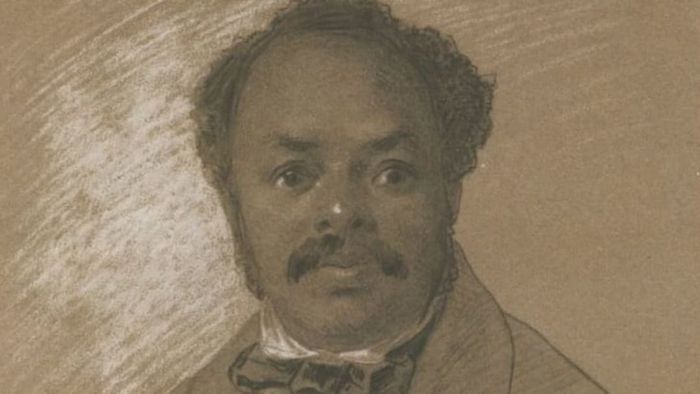

Portrait of Ira Aldridge in 1858 | Taras Shevchenko, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Portrait of Ira Aldridge in 1858 | Taras Shevchenko, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainRefusing to be discouraged, Aldridge took both Othello and The Padlock on a national tour across Britain’s provincial theaters. This bold move turned out to be a tremendous success.

During his tour, Aldridge won over a large new following and, in 1828, became the manager of the Coventry Theatre, making him the first Black theater manager in Britain. He also made a name for himself by using his time between performances to lecture on the horrors of slavery and lend his growing support to the abolitionist cause.

Next, Aldridge took his tour to Ireland, where he quickly became a sensation. With tensions still high between Ireland and Britain, Irish audiences embraced him, especially after hearing of his mistreatment in London. In one memorable speech in Dublin, Aldridge told his audience, 'Here the sable African was free / From every bond, save those which kindness threw / Around his heart, and bound it fast to you.'

By the 1830s, Aldridge was performing across Britain and Ireland in his own one-man show, blending powerful dramatic monologues and Shakespearean recitals with songs, personal stories, and lectures on abolitionism. In an effort to counter the blackface minstrel shows that were popular at the time, he began performing in 'whiteface,' portraying characters such as Shylock, Macbeth, Richard III, and King Lear. When the notorious Thomas Rice brought his racist 'Jump Jim Crow' minstrel act to England, Aldridge cleverly and boldly incorporated one of Rice’s skits into his own performance, parodying the parody and rendering Rice’s crude act ineffective—while simultaneously showcasing his own extraordinary skill as a performer.

Aldridge's popularity was such that he could have easily spent the rest of his days in England, performing to full houses night after night. However, by the 1850s, word of his extraordinary acting abilities had spread far and wide. Always eager to embrace new challenges, Aldridge decided to form a troupe of actors in 1852 and set off on a European tour.

In just a few months, Aldridge became one of the most celebrated actors across Europe. Critics praised his performances, with one German writer declaring him to be 'the greatest of all actors.' A Polish critic remarked, 'Though most of the audience did not speak English, they could still feel what was conveyed through the actor's face, eyes, lips, voice, and entire body.' His fame attracted admirers, including Danish author Hans Christian Andersen and the famed French poet Théophile Gautier, who lauded Aldridge’s portrayal of King Lear in Paris. Soon, royalty took notice: Friedrich-Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, awarded him the Prussian Gold Medal for Art and Science, and in Saxe-Meiningen, Aldridge was made a Chevalier Baron of Saxony in 1858.

Aldridge continued touring Europe for another decade, using his earnings to purchase two properties in London, one of which was on Hamlet Road. But by the time the Civil War ended, America called to him. In his late fifties, Aldridge, still eager for new challenges, planned one final venture—a 100-date tour of post-emancipation America. Venues were secured, contracts signed, and excitement for Aldridge's long-anticipated homecoming tour began to build.

Sadly, Aldridge's plans were never realized. Just weeks before his intended departure, he fell ill with a lung condition while touring in Poland. He passed away in Łódź in 1867 at the age of 60 and was buried in the city's Evangelical Cemetery.

Following his death, several theaters and troupes of Black actors, including Philadelphia's renowned Ira Aldridge Troupe, were established in his honor. Countless Black playwrights, performers, and directors have since viewed him as a profound influence on their own work and creativity.

In August 2017, marking the 150th anniversary of Aldridge's death, Coventry, England, unveiled a blue heritage plaque in the city's center, honoring Aldridge's legacy in the theater. Even more than a century after his passing, the remarkable life of Ira Aldridge remains unforgettable.