Widely regarded as one of the most impactful Brutalist structures ever built, the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille stands as a key project by the legendary 20th-century French architect, Le Corbusier. This iconic structure is one of 17 of his works that have been honored by UNESCO, earning recognition as a site of global architectural significance. Flickr/Denis Esakov/(CC 3.0)

Widely regarded as one of the most impactful Brutalist structures ever built, the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille stands as a key project by the legendary 20th-century French architect, Le Corbusier. This iconic structure is one of 17 of his works that have been honored by UNESCO, earning recognition as a site of global architectural significance. Flickr/Denis Esakov/(CC 3.0)When discussing the most stunning buildings around the world, Brutalist architecture might not immediately come up in conversation. While structures like the Palace of Versailles or the more modern Sacré-Coeur Basilica are likely contenders, Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation in Marseille probably won't be the first on anyone's list.

Completed in 1952, however, this monumental building is considered by ArchDaily to be the architect's 'most significant and inspiring' work. Constructed from béton-brut concrete—an affordable material in post-war Europe—the Unité d'Habitation housed 1,600 residents and offered communal spaces for dining, shopping, and socializing. Its raw, heavy aesthetic laid the foundation for Brutalism, a style that continues to find its rightful place in the hearts of architecture enthusiasts worldwide.

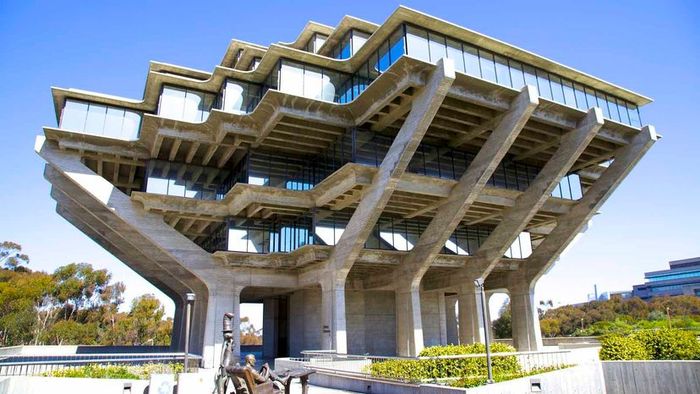

The renowned Geisel Library at UCSD was initially named the Central Library, but in 1995, it was renamed to honor Audrey and Ted Geisel (better known as Dr. Seuss) after Audrey contributed $20 million to the university. The library is also home to more than 20,000 original works and memorabilia from Dr. Seuss.

What Exactly Is Brutalism?

Brutalism is an architectural movement that emerged after World War II, defined by bold, imposing forms, distinctive shapes, and a heavy reliance on raw, unfinished materials, according to Brandon Buck, RIBA and design director at global firm Perkins&Will. Buck is also overseeing the renovation of the Brutalist Richard Seifert building at 41 Tower Hill, London.

The name 'Brutalism' derives from its characteristic unfinished surfaces—the 'béton brut' (raw concrete) used in the design. This style mainly utilizes exposed concrete and, occasionally, brick, complemented by a simple, monochromatic color scheme. While materials like steel, timber, and glass may be used, they play a secondary role in the construction.

"It's hard not to be struck by the boldness of Brutalist architecture," remarks Buck, who compares the experience of walking through these buildings to visiting a modern art museum—whether or not you appreciate everything, it forces you to stop, reflect, and evoke emotion.

Brandon Buck, the design director at global design firm Perkins&Will, is spearheading the team working on the renovation of the Brutalist structure at 41 Tower Hill, London, as shown in the image here.

Perkins&Will

Brandon Buck, the design director at global design firm Perkins&Will, is spearheading the team working on the renovation of the Brutalist structure at 41 Tower Hill, London, as shown in the image here.

Perkins&Will

Is Brutalism in Vogue or Out of Favor?

While the term 'Brutalism' comes from the French 'béton brut,' meaning raw concrete, rather than implying any 'brutal' connotation, it's surprising how negatively the style is often perceived.

"If you consider popular culture, there are many films that have cast Brutalist buildings in a harsh light, influenced by the surroundings of those structures," Buck explains. He points to the housing estate featured in the film "A Clockwork Orange" as a prime example. These portrayals in mainstream media have contributed to Brutalism's harsh reputation.

Brutalist structures are often labeled as ugly or unpopular. However, it's crucial to remember that the style had a significant purpose and was shaped by its historical context.

"Back in the late '50s and early '60s, concrete was relatively inexpensive," says Buck. In the postwar period, there was a surplus of energy and a strong demand for labor, making concrete a practical choice for construction. It became especially popular for building monumental government and university buildings, as well as social housing projects.

During that time, the public embraced it. Architects who championed the style "wanted to convey a sense of strength through these massive, fortress-like structures," Buck elaborates.

Despite its emphasis on practicality and authority, Brutalist architecture also had a more gentle side, showcasing the rawness and imperfections of handcrafted materials.

"There’s something deeply human about that," says Buck.

Integrating Brutalism into Home Décor and Interior Design

If you want to bring Brutalist style into your home, you don’t need to live in a mid- to late-20th century building. Today, Brutalist-inspired décor is easy to find. A piece of Brutalist-style sculpture could also serve as an excellent accent.

"There’s a growing interest in having such pieces in people’s homes and office spaces," says Buck.

According to Vault, modern Brutalist interiors often start with a bold, textured foundation, focusing on natural materials. What's new, however, is the addition of polished chrome metallics. The clean, geometric shapes provide a striking contrast to more vibrant palettes, or those featuring elements like brass and copper, Buck explains.

"The natural tone of concrete and its inherent imperfections complement other material palettes in interior design," he notes.

Is Brutalism on the Rise Again?

After falling out of favor in the 1980s, partly due to its links to totalitarianism, as noted by Jessica Stewart for My Modern Met — think socialist modernism — Brutalism seems to be undergoing a revival. While new Brutalist buildings aren’t emerging as they did in the 1960s, existing ones are being revisited, revamped, and retrofitted.

"This is definitely a major trend right now," says Buck. The robust nature of Brutalist buildings often allows for the addition of extra stories, enabling contemporary architects to preserve the building’s essence while improving the space to better serve the community.

"People are beginning to recognize the value of Brutalism and are adapting some of its features in fresh ways," he explains.

In many Brutalist designs, the fenestration (or window placement) is limited or minimized compared to the vast expanses of concrete. One common update involves enlarging these openings. This was a key aspect of the debated 2018 renovation of the Marcel Breuer-designed Central Atlanta Library by Cooper Carry. Another common improvement involves recladding the façade to enhance building performance, especially in terms of heat regulation, says Buck.

Due to their original purpose, architectural integrity, and strong association with renowned architects, Brutalist structures are enjoying a resurgence in the 21st century. Whether you appreciate them or not.

"They definitely stand out," says Buck. "They tend to evoke a reaction."

Iconic Brutalist Structures

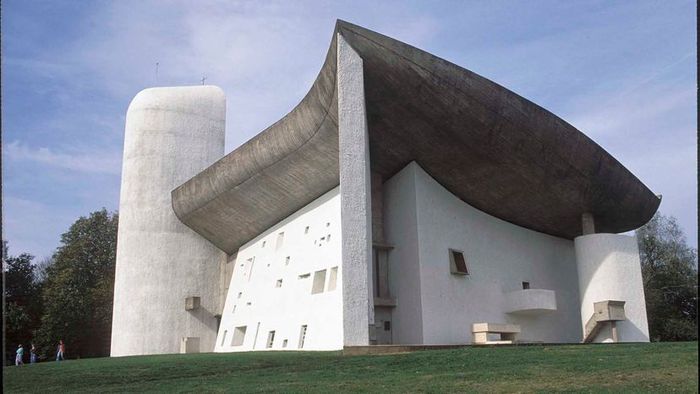

Brutalist buildings can be spotted all over the globe; many may have crossed your path without you even noticing. Aside from Le Corbusier's foundational Unité d'Habitation, his Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, is deemed "one of the most significant buildings of the 20th century," according to Dezeen.com.

Widely regarded as Le Corbusier's masterpiece, the Notre Dame du Haut chapel is defined by a massive, sweeping concrete roof that marks a departure from the more utilitarian style of the architect's earlier designs.

Sobli/RDB/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Widely regarded as Le Corbusier's masterpiece, the Notre Dame du Haut chapel is defined by a massive, sweeping concrete roof that marks a departure from the more utilitarian style of the architect's earlier designs.

Sobli/RDB/ullstein bild via Getty ImagesIn the U.K., Alison and Peter Smithson, the husband-and-wife duo, "guided British Brutalism through the latter half of the 20th century," according to ArchDaily. They are known for designing modern housing with "streets in the sky," the headquarters of The Economist, and a building at Oxford University.

Swiss-British architect Richard Seifert was a prolific creator of Brutalist buildings, including the 34-story Centre Point in London, described as a 'beehive' grid of glass and concrete. The building was left unused for decades but has since been redeveloped into a luxury residential tower. Another notable Brutalist landmark in London is the Barbican Centre and Estate, designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, who were inspired by Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation.

The architects of London's iconic Barbican Centre, Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, drew inspiration from Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation.

Jordi Prats/Shutterstock

The architects of London's iconic Barbican Centre, Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, drew inspiration from Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation.

Jordi Prats/ShutterstockAnother groundbreaking example of "reimagining apartment living," Moshe Safdie's Habitat 67, created for the 1967 World's Fair in Montreal, blends the concrete of Brutalism with the principles of Japanese Metabolism, resulting in a striking design of modular cubes.

Habitat 67, conceived by Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie as the Canadian Pavilion for the 1967 World Exposition, was originally envisioned as an experimental solution to provide high-quality housing within densely populated urban areas.

Taxiarchos228/Wikimedia/(CC BY-SA 3.0)

Habitat 67, conceived by Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie as the Canadian Pavilion for the 1967 World Exposition, was originally envisioned as an experimental solution to provide high-quality housing within densely populated urban areas.

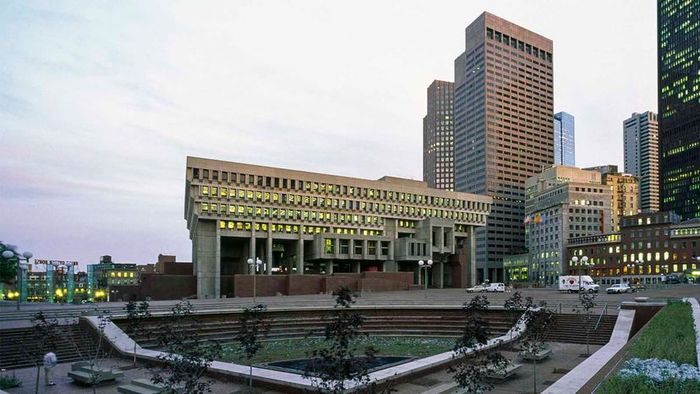

Taxiarchos228/Wikimedia/(CC BY-SA 3.0)Boston boasts several iconic Brutalist buildings, including Boston City Hall, often referred to as a "concrete fortress". The design emerged from an international competition, with the winning concept developed by Gerhard Kallmann, Noel McKinnell, and Edward Knowles, all of whom were influenced by Le Corbusier.

The design of Boston City Hall emerged from an international competition, with the winning proposal developed by Gerhard Kallmann, Noel McKinnell, and Edward Knowles, who were influenced by the work of Le Corbusier.

DEA/M. BORCHI /De Agostini via Getty Images

The design of Boston City Hall emerged from an international competition, with the winning proposal developed by Gerhard Kallmann, Noel McKinnell, and Edward Knowles, who were influenced by the work of Le Corbusier.

DEA/M. BORCHI /De Agostini via Getty ImagesThe Geisel Library, one of the most iconic Brutalist structures, is located at the University of California San Diego. Designed by William Pereira, it was completed in 1970 and constructed using reinforced concrete and glass. The building features a two-story pedestal that supports six cantilevered stories above it.

Another well-known Brutalist masterpiece is the Geisel Library at the University of California San Diego, which was designed by William Pereira.

Geisel Library

Another well-known Brutalist masterpiece is the Geisel Library at the University of California San Diego, which was designed by William Pereira.

Geisel Library