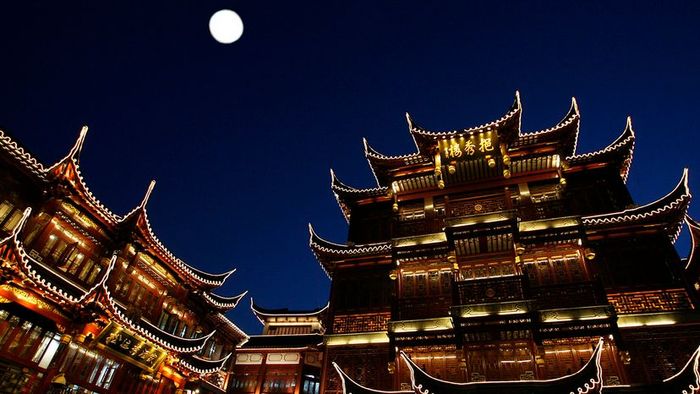

The full moon casts its glow over the Yuyuan Gardens in Shanghai, China. In the near future, a 'fake' moon might light up Chengdu, a city in Sichuan province. Lucas Schifres/Contributor/Getty Images

The full moon casts its glow over the Yuyuan Gardens in Shanghai, China. In the near future, a 'fake' moon might light up Chengdu, a city in Sichuan province. Lucas Schifres/Contributor/Getty ImagesA new artificial moon is on the horizon. A Chinese space contractor has revealed plans to launch a satellite in 2020 designed to reflect artificial moonlight. The satellite aims to serve as a supplemental streetlight, using reflective material to provide additional lighting for the people of Chengdu, a city in Sichuan province, after dark.

While some critics express concern about the environmental effects of the project, supporters argue that the satellite could significantly reduce electricity costs, saving the Chengdu government an estimated $173 million annually. Of course, this depends on the satellite's performance. To ensure a successful launch, the satellite will undergo thorough testing before it is deployed in populated regions.

Low Orbit, High Concept

The announcement of this ambitious project was made public at a conference on October 10, 2018, by entrepreneur Wu Chungfeng. He is the chairman of the Chengdu Aerospace Science and Technology Microelectronics System Institute Co., a company that collaborates with the Chinese Space Program. Currently, there has been no official confirmation from either the national government or the city of Chengdu regarding the satellite’s development.

Nevertheless, Chungfeng revealed that prestigious institutions such as the Harbin Institute of Technology and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation have endorsed the project, believing it is ready for trial testing.

Our natural moon doesn’t produce light; its glowing appearance is a result of sunlight being reflected off its surface. The proposed ‘artificial moon’ from China plans to employ the same method. According to Chungfeng, the satellite will utilize a reflective coating to channel sunlight toward Chengdu. Some experts hypothesize that large, solar panel-like structures could be attached to the satellite for this purpose.

The plan is to have the satellite orbit in low-Earth space at a height of 310 miles (500 kilometers). This would place it above the International Space Station's typical orbit of 248 miles (400 kilometers) and below the Hubble Space Telescope's usual altitude of around 353 miles (569 kilometers). Naturally, all of these objects will be much closer to Earth than the actual moon, which is positioned 225,623 miles (363,104 kilometers) from us at its closest approach.

When the Moon Hits Your Eye

It is said that the artificial moon could shine up to eight times brighter than the natural moon, though it will not light up the whole sky. Instead, it will cast a subtle, dusk-like glow, as described by a Harbin Institute of Technology scientist. According to Chungfeng, under ordinary conditions, the satellite will appear roughly one-fifth as bright as a typical streetlight when viewed with the naked eye from Earth.

Should the brightness become excessive, human operators will have the ability to control the satellite's intensity or switch it off completely.

Moreover, Chungfeng revealed that the satellite can direct its light onto specific areas of Earth, illuminating regions with diameters ranging from 6.2 to 50 miles (10 to 80 kilometers). While this won’t be enough to cover all of Chengdu, which spans 4,787 square miles (12,400 square kilometers), if it lights up just 19 square miles (50 square kilometers), Chengdu could reduce its urban lighting costs by 1.2 billion yuan — around $173 million — annually.

A Time For Reflection

In the 1990s, the Russians attempted something similar. In an effort to enhance productivity in polar regions, astro-engineer Vladimir Sergeevich Syromyatnikov developed what The New York Times referred to as a "space mirror." This satellite, called Znamaya (meaning "banner"), was equipped with a large aluminum-coated plastic sheet that could be deployed at will.

After spending a considerable time on the Mir space station, Znamaya was released into orbit on February 4, 1993. It emitted a beam of light at full-moon brightness directed toward Europe, although many areas were unable to see it due to cloud cover. A few days later, Znamaya burned up in the atmosphere. However, a larger version of the spacecraft, Znamaya 2.5, was launched on February 5, 1999. Unfortunately, it encountered problems when its reflective mirror got caught on an antenna and tore, leading to the termination of the mission.

In January 2018, a New Zealand company made an attempt to replicate moonlight with the controversial launch of Rocket Lab's "Humanity Star," which was essentially a large disco ball with 76 reflective panels. The object, which orbited Earth in 90-minute intervals, disintegrated prematurely on March 23.

Is This a Bright Idea?

The concept of artificial moons is not entirely new, but if Chungfeng's satellite succeeds, it will mark a new era. Should the new satellite function as intended, China plans to launch three more light-reflecting satellites into space in 2022.

There are concerns about the potential increase in light pollution caused by this project. Could the manmade moons disrupt astronomers by obscuring the stars in certain locations? And what will the impact be on wildlife, such as birds and sea turtles, whose navigation is influenced by natural moonlight? Chungfeng acknowledges these concerns and assures that such factors are being carefully considered. He mentions that the satellites have been in the works for several years and will be tested in an "uninhabited desert," where the light beams are expected to have minimal impact on city dwellers or observatories.

Tucson, Arizona, is home to streetlights designed with astronomers in mind. As observatories play a significant role in the local economy, the city enforces "dark sky" regulations aimed at reducing light pollution. For instance, the municipal streetlights now feature low-luminosity bulbs to minimize their brightness and protect the view of the night sky.