Doubleday’s sales team gazed intently at the screen, where the proposed cover for Jaws was displayed. The artwork, inspired by Benchley’s idea, featured the bleached jawbone of a shark, its mouth wide open, poised to devour unsuspecting beachgoers. The novel, a suspenseful thriller by the then-unknown author, centered on a menacing great white shark wreaking havoc in a coastal town.

However, the sales team foresaw issues. To them, the image didn’t evoke a shark’s jaw but rather resembled a toothed vagina or the unsettling Freudian concept of vagina dentata.

A subsequent redesign featuring a shark, completed just before publication, sparked new controversy—this time drawing comparisons to male genitalia. (It appeared the Doubleday team had a singular focus.) After numerous revisions and contributions from various artists, the final cover emerged as one of the most iconic in literary history: a shark rising toward the surface, with a swimmer perilously close to its deadly jaws. This striking imagery was later adapted for the 1975 Steven Spielberg film, cementing its place as one of the most recognizable movie posters ever created.

Despite its iconic status, the artwork for Jaws remains shrouded in mystery. While copies are widespread, locating the original painting is a far more challenging endeavor.

A View of the Sea

Peter Benchley penned Jaws to explore a lingering fascination: What if a shark decided to strike a popular seaside resort? His manuscript caught the attention of Doubleday editor Tom Congdon, who transformed Benchley’s draft—initially laden with humor—into a potential blockbuster.

This left Doubleday with the task of effectively marketing the novel. The responsibility landed on art director Alex Gotfryd, who, in 1973, oversaw more than 700 book covers each year. Gotfryd embraced Benchley’s concept: a stark depiction of a shark’s jawbone, with the fictional town of Amity ensnared within its teeth. (Congdon proposed adding an ominous red sky, which Gotfryd included in the final design.)

Peter Benchley, the author of 'Jaws,' proposed a concept for the book's cover art. | Peter Jones/GettyImages

Peter Benchley, the author of 'Jaws,' proposed a concept for the book's cover art. | Peter Jones/GettyImagesArtist Wendell Minor’s design was unveiled at an April 1973 sales conference, where it faced resistance due to its unintended anatomical resemblance. Concerned, Congdon consulted Gotfryd and proposed a redesign featuring a realistic shark, complete with its full body.

“The cover isn’t large enough,” Gotfryd argued. “It’ll end up looking like a tiny fish.”

As a compromise, they agreed on a minimalist cover featuring only the title and Benchley’s name. However, this approach didn’t sit well with Bantam Books, which had invested $575,000 for the paperback rights to Jaws. Oscar Dystel, Bantam’s publisher, feared that a text-only cover might mislead readers into thinking it was a book about dental care.

To address Dystel’s concerns, Gotfryd enlisted renowned artist Paul Bacon, known for his work on iconic covers like Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. (Bacon’s portfolio would eventually include over 6,500 cover designs.)

Bacon’s design featured a shark rising toward the surface of shadowy waters. To address Gotfryd’s worry about the shark appearing too small, Bacon included a swimmer, providing a clear sense of scale. (The cover can be viewed here.)

Congdon and Gotfryd reluctantly accepted the new design. “We noticed the updated version resembled a toothed phallus,” Congdon remarked. It seemed that crafting the perfect cover for Jaws was an art in itself, and they hadn’t yet mastered it.

Jaws Redesigned

The hardcover edition of Jaws (priced at $6.95) became an instant success upon its February 1974 release, with 75,000 copies in circulation by April. However, Bantam executives felt Bacon’s cover lacked a certain impact. With significant investment in Jaws and ambitions to sell 5 million paperback copies ($1.95 each) upon its January 1975 release, Bantam sought a fresh approach.

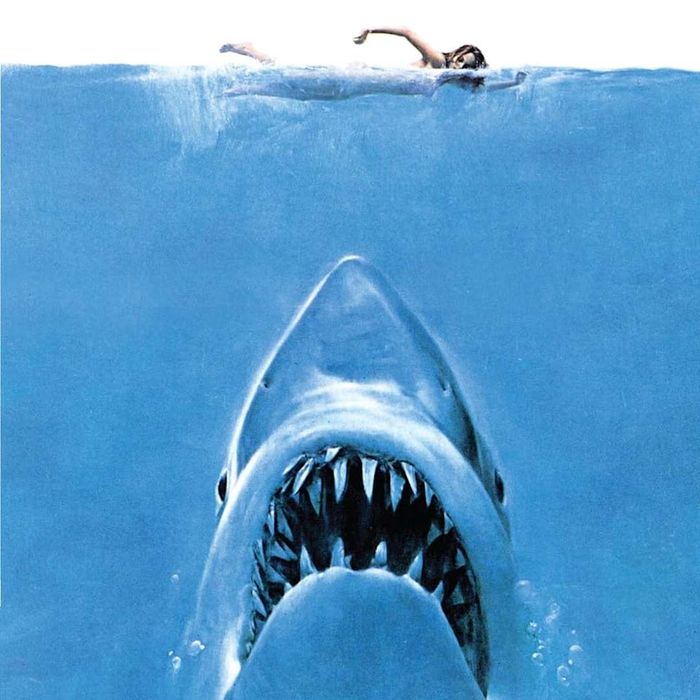

Bantam’s art director Len Leone enlisted Roger Kastel, a Korean War veteran and seasoned illustrator. Kastel was tasked with making the shark more menacing, emphasizing its razor-sharp teeth. (It’s unclear if anyone explicitly instructed him to avoid phallic imagery.) While Bacon’s layout was retained, the shark and swimmer underwent a dramatic transformation.

Kastel visited the American Museum of Natural History to study the shark exhibit, but renovations forced its closure. Undeterred, he sketched and photographed sharks, including mako sharks, using an easel. (This led to the shark in the illustration resembling a mako more than a great white.) These references gave the fictional predator a more realistic appearance, with a broader body and a larger mouth.

Roger Kastel’s book cover design for 'Jaws.' | Amazon

Roger Kastel’s book cover design for 'Jaws.' | AmazonFor the swimmer, Kastel seized a creative opportunity. While photographing a model for Good Housekeeping, he asked her to pose on a stool, mimicking a swimming motion. He then combined these images with a vibrant blue ocean, a stark contrast to the dark waters in Bacon’s version.

Kastel’s oil painting also introduced a notable change: the swimmer was depicted without a bathing suit. While no explicit details were shown, it was evident the swimmer was nude. This bold choice led to the paperback being banned in more conservative areas. For instance, in Tampa, Florida, an anti-obscenity law prompted the removal of Jaws from shelves, alongside issues of Time magazine featuring Cher in a tight-fitting dress.

“I thought my illustration career was over,” Kastel said to Collector’s Weekly in 2012. “I couldn’t have been more mistaken. Bantam adored the publicity. It boosted book sales tremendously.” However, Kastel’s joy was fleeting.

A Vanishing Masterpiece

Kastel’s artwork so vividly depicted the clash between species that Universal, the studio producing the film adaptation, adopted it almost unchanged for the movie poster, with only a splash of water added to partially conceal the swimmer’s chest. (The title font was modified, with the j designed to resemble a fishhook.) Bantam’s Oscar Dystel was perhaps overly generous, allowing Universal to use the artwork without charge. Still, the film served as excellent promotion for Bantam’s paperback edition.

Universal utilized Roger Kastel’s book cover art for the movie’s promotional materials. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImages

Universal utilized Roger Kastel’s book cover art for the movie’s promotional materials. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImagesThat decision drastically altered the fate of the original artwork. According to Kastel, the last time he saw his painting was during a book tour. After being sent to Universal, it vanished, and Kastel never laid eyes on it again.

Kastel speculated that the artwork might have been lost in Universal’s archives. A more troubling possibility is that someone associated with the studio may have taken it.

In a 2022 article for Daily Art Magazine, Matthew Kastel, the artist’s son, revealed that his father had tried to uncover the truth through Bantam publisher Oscar Dystel. However, Dystel only relayed that Universal executives had no information about the painting’s location. Matthew asserted his father’s ownership of the piece and called on Universal to locate it.

The painting remains missing, and Kastel passed away in 2023. While the absence of his Jaws artwork—which could command millions at auction if found—was a lingering disappointment, the project paved the way for another iconic creation: the poster for the 1980 Star Wars sequel, The Empire Strikes Back.