Many of cinema’s greatest masterpieces, including Gone With the Wind and The Godfather, originated from literary works—and Jaws was no different. Directed by Steven Spielberg and released in 1975, this shark-filled blockbuster was adapted from Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel. Much like its terrifying predator, the book surfaced unexpectedly, captivating and terrifying readers worldwide. Discover how Benchley transformed a simple newspaper idea into a gripping, gory modern take on Moby-Dick.

Jaws secured its publication deal with just one compelling page.

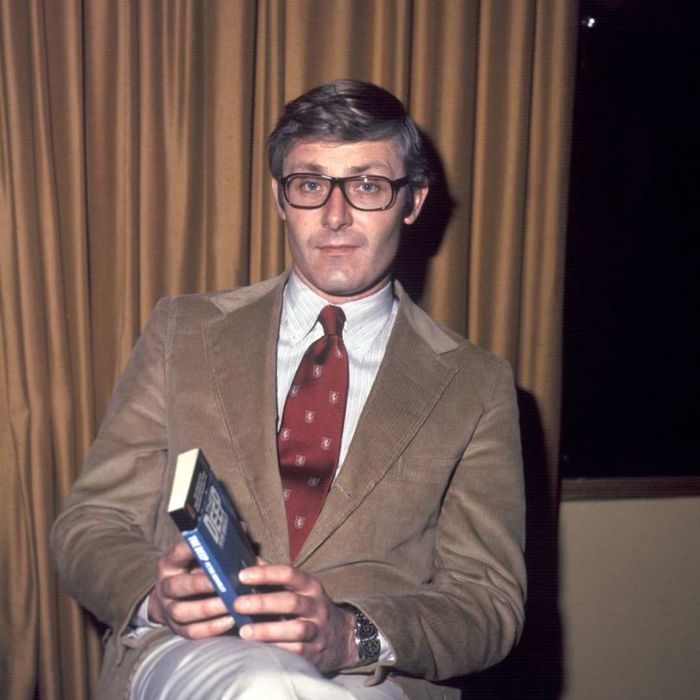

Peter Benchley, the author of 'Jaws.' | Peter Jones/GettyImages

Peter Benchley, the author of 'Jaws.' | Peter Jones/GettyImagesBorn on May 8, 1940, in New York City, Peter Benchley developed a deep passion for the ocean from a young age. His family frequently visited Nantucket, where he and his father, author Nathaniel Benchley, fished for swordfish. (Benchley once mentioned that he had “dissected” sharks during these trips, preserving their jawbones as souvenirs.) Years later, in 1965, Benchley read about a shark caught off Montauk, Long Island, sparking his fascination with what he would later describe as “ancient predatory creatures.”

During a lunch meeting in 1971 with Doubleday editor Thomas Congdon, Benchley proposed a novel about a shark terrorizing a peaceful coastal town. Congdon requested a one-page summary, which ultimately persuaded Doubleday to offer Benchley a $1000 advance to develop the story that would become Jaws.

The initial version of Jaws leaned a bit too heavily on humor.

Peter Benchley initially added too much humor to 'Jaws.' | United Archives/GettyImages

Peter Benchley initially added too much humor to 'Jaws.' | United Archives/GettyImagesIn March 1972, Benchley delivered the first four chapters of Jaws to Congdon. The editor was unimpressed. In a memo to a colleague, he noted, “The book’s opening is fantastic, and the shark scenes are strong throughout. However, the rest feels rather lackluster…” Congdon specifically criticized Benchley’s tendency to include jokes for the characters. “The author aims for both laughs and scares, but the combination falls flat.”

Congdon urged Benchley to revise the chapters, eliminating the humor, which Benchley did willingly. This effort secured him a $7500 advance, including the initial $1000. The final manuscript received high praise, leading others at Doubleday to join Congdon in supporting the book.

Jaws wasn’t Peter Benchley’s debut novel.

Peter Benchley holding a book industry award. | Express Newspapers/GettyImages

Peter Benchley holding a book industry award. | Express Newspapers/GettyImagesWhile Jaws later led The New York Times to hail Benchley as the most successful debut novelist ever, it wasn’t his first publication. A Harvard alumnus, Benchley worked at Newsweek and the Washington Post. In 1964, he published Time and a Ticket, a memoir detailing his travels after graduation. That same year, he also released the children’s book Jonathan Visits the White House. (In 1967, Benchley had the opportunity to visit the White House himself when he became a speechwriter for Lyndon Johnson.)

Jaws might have been named What’s That Noshin’ on My Laig?**

Peter Benchley contemplated numerous titles for 'Jaws.' | Avalon/GettyImages

Peter Benchley contemplated numerous titles for 'Jaws.' | Avalon/GettyImagesJaws stands as one of the most iconic titles in modern literature and film, perfectly capturing the menace of a predator hunting humans. However, Benchley and his editors went through extensive deliberations to settle on it. Over 200 potential titles were considered, including Silence in the Water (Benchley’s initial choice), The Jaws of the Leviathan, The Summer of the Shark, The Year They Closed the Beaches, and a humorous suggestion from Benchley’s father: What’s That Noshin’ on My Laig [Leg]?

Benchley insisted on avoiding the word shark in the title, worried that bookstores might place it in the nature section. Eventually, he suggested to Congdon that since both liked the word jaws, they should simply title it Jaws.

A romantic scene in Jaws was considered out of place for the novel.

Although Thomas Congdon was a staunch supporter of Benchley at Doubleday, he objected to a scene depicting intimacy between police chief Martin Brody and his wife Ellen. “Wholesome marital relations don’t belong in this kind of story,” Congdon remarked, believing a potential bestseller needed more sensational elements. In response, Benchley introduced an affair involving Brody’s wife and marine biologist Matt Hooper. (This subplot was omitted from the film adaptation, which Benchley initially scripted before Spielberg brought in Carl Gottlieb. Ironically, Gottlieb reintroduced humor into the screenplay after Congdon had worked to remove it from the book.)

Jaws nearly included a real shark tooth as a promotional feature.

Shark teeth were contemplated for promotional purposes. | Alexis Rosenfeld/GettyImages

Shark teeth were contemplated for promotional purposes. | Alexis Rosenfeld/GettyImagesCongdon was so excited about Jaws that he brainstormed creative marketing strategies. One idea was mailing book reviewers a real shark tooth alongside a copy of the novel. However, after his assistant found that a single tooth could cost over $40, the plan was abandoned.

Benchley never anticipated the success of Jaws.

Peter Benchley doubted the success of 'Jaws.' | McCarthy/GettyImages

Peter Benchley doubted the success of 'Jaws.' | McCarthy/GettyImagesAt the time, the publishing industry believed debut novels rarely gained traction, as authors typically needed a series of works to build a loyal audience. Benchley assumed Jaws wouldn’t make waves, either as a book or a potential film. “No one expected Jaws to succeed,” he remarked later. “It was a first novel, and first novels don’t sell. It was about a fish, for heaven’s sake—who cared about fish? Plus, we all thought it couldn’t be adapted into a movie because no one could train a great white shark, and Hollywood’s special effects weren’t advanced enough to create a believable mechanical shark.”

Jaws became a massive hit in paperback.

Peter Benchley with another bestselling paperback, 'The Deep.' | Avalon/GettyImages

Peter Benchley with another bestselling paperback, 'The Deep.' | Avalon/GettyImagesJaws hit shelves in January 1974, validating Congdon’s instincts. It stayed on bestseller lists for 45 weeks, partly due to its selection by book clubs. While Doubleday retained hardcover rights, Bantam acquired paperback rights for $575,000. By the time the Jaws movie premiered in June 1975, the paperback had 9 million copies in circulation.

However, Jaws wasn’t Benchley’s only lucrative venture. In 1978, he secured $2.15 million for the film rights to his novel The Island, setting a record for the highest price paid for non-musical film rights at the time.

The film rights for Jaws were sold before the book even hit stores.

The film adaptation of 'Jaws' was in development before the book’s publication. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImages

The film adaptation of 'Jaws' was in development before the book’s publication. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImagesUniversal secured the rights to Jaws before its publication for $175,000, anticipating—like Congdon—that the story would resonate with audiences. “We had no clue the novel would become a bestseller,” Steven Spielberg admitted. “We committed to the project when it was just 400 pages of widely spaced galleys.”

Spielberg and Universal were deeply invested in the book’s success. To boost its profile, they distributed copies to influential figures, ranging from socialites to studio staff and even restaurant proprietors.

According to Benchley’s recollection, the film adaptation nearly didn’t happen: A Universal script reader who praised the book gave it an ‘A’ grade, but the lowercase ‘a’ made it appear as a ‘C.’ This mix-up caused Universal to be one of the last studios to bid on the project.

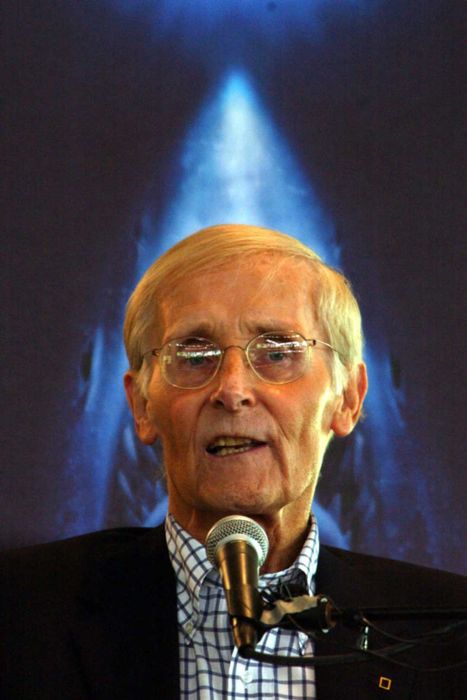

Benchley later expressed regret over how Jaws portrayed sharks as villains.

Peter Benchley in 2005. | Darren McCollester/GettyImages

Peter Benchley in 2005. | Darren McCollester/GettyImagesBenchley initially portrayed the shark in Jaws as an almost mythical predator. However, as awareness grew about shark conservation and public fears, he later regretted his role in fueling the panic. He dedicated himself to supporting shark preservation efforts until his passing in 2006. “What I’ve learned since writing Jaws is that there’s no such thing as a rogue shark with a craving for human flesh,” he stated in 2000. He further reflected: “If Jaws were written today, the shark couldn’t be the antagonist; it would have to be depicted as the victim, as sharks globally are far more endangered than dangerous.”