The artist highlighted four fundamental shapes on screen. 'With the ability to sketch these basic forms—ball, cone, cube, and cylinder,' he assured his audience, 'you can create a complete picture on your very first attempt.' A title card flashed—Learn to Draw—followed by his name in chalk: Jon Gnagy.

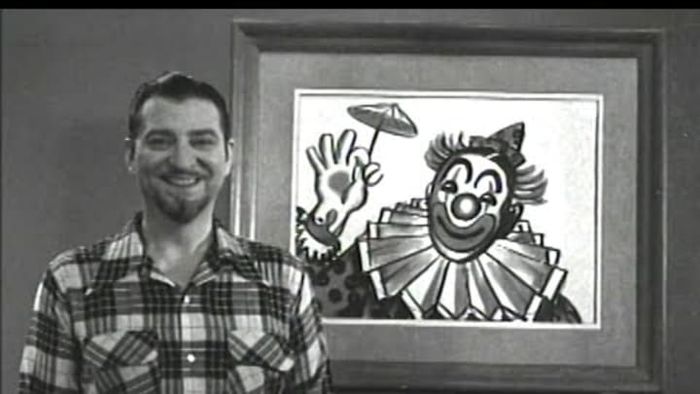

Starting in 1946, during the infancy of television, and continuing until 1960, Gnagy delivered a consistent weekly message: Anyone, regardless of skill level, could create art by mastering a few foundational techniques. Families gathered in living rooms to follow his lessons, while bar patrons scribbled on napkins to practice his methods. Countless individuals, including a young Andy Warhol, learned to sketch landscapes, farms, ships, and clowns under Gnagy's guidance. With his plaid shirts and Van Dyke beard, Gnagy became a calming artistic figure long before Bob Ross gained fame.

Despite his popularity, Gnagy didn't earn a single dollar from his television appearances, contrary to what many viewers might have assumed.

Drawn to It

Gnagy entered the world in 1907, long before television existed. Growing up on a farm in Varner, Kansas, he was part of the Mennonite community, a Christian denomination with similarities to the Amish. His father, a skilled cabinetmaker, noticed his son’s artistic inclinations, though Jon’s medium was pencil and ink rather than wood.

As a young adult—or nearly so at 17—Gnagy began exploring life beyond his hometown, moving to Tulsa, then New York, and later Philadelphia, where he worked in public relations and advertising. In 1927, he married Mary Jo Hinton, a fellow artist, and they welcomed two children, Polly and Stephen. Gnagy’s formal art education didn’t begin until 1943, when he started taking lessons. He eventually transitioned into teaching, traveling and sharing his expertise in drawing and painting.

In 1946, Gnagy quoted the French post-impressionist Paul Cézanne, stating, 'Cézanne observed that all of nature can be interpreted through cubes, spheres, cones, and cylinders. When these elements are combined to achieve harmony in line, value, size, and shape, a true work of art emerges.'

During World War II, the production of TVs and their components had stalled, but post-war, major cities began embracing the potential of television. New York alone had roughly 3800 sets, with demand rapidly increasing. At the time, television was seen as a promising educational tool, a vast classroom without the distractions of reality shows or scripted dramas.

In May 1946, NBC featured Gnagy in a short segment of Radio City Matinee, where he sketched an oak tree. It was a challenging debut, as Gnagy adapted to teaching within the tight time limits of television.

Despite the medium's infancy—likely reaching fewer than 200 viewers—his performance impressed NBC enough to grant him his own show, You Are an Artist, later that year. Each episode featured Gnagy breaking down a scene into simple shapes, like turning squiggles into a snowy mountain or an oval into a flock of geese.

The series lasted nearly three years before networks shifted focus to scripted dramas and game shows, sidelining educational content like Gnagy’s program. For a time, he disappeared from the airwaves.

Sketch Show

Gnagy later transitioned to a role as a television weatherman, eventually hosting The Jon Gnagy Fishing and Weather Show. His second art series, Draw With Me (later rebranded as Learn to Draw), debuted in 1950 as a syndicated program. Like its predecessor, it guided viewers through creating art step by step. Though based in California, Gnagy traveled to New York annually to film 13 episodes.

Gnagy often prepared a detailed 2000-word script, which he would recite to someone for feedback. If any part of his instructions caused confusion, he would refine it. His aim was to transform art into an accessible and practical activity.

In a 1952 interview with The New York Times, Gnagy clarified, 'Let’s not label my program as art. It’s a blend of entertainment and education. My mission is to inspire as many people as possible to sketch independently and observe their surroundings. I want to elevate their doodles—something everyone does—into more meaningful creations. By being observant and mastering a few drawing principles, anyone can recreate what they see from memory.'

Instead of receiving a salary for hosting, Gnagy adopted an early version of a home shopping model. During each episode, he encouraged viewers to buy a Learn to Draw art kit from local stores. The kit included pencils, chalk, a shading stamp, a sketch pad, and an instructional book, with Gnagy earning a share of the sales. Later, he broadened the product line to include kits like Learn Pastel Painting With Jon Gnagy and Learn Watercolor Painting With Jon Gnagy.

Over time, interest in Learn to Draw waned among station programmers. As a 15-minute show, it didn’t fit well into the standard 30- to 60-minute time slots. By 1960, the program had virtually disappeared from television.

In the 1970s, Gnagy semi-retired and focused on private art instruction through The Jon Gnagy School of Painting, as well as delivering art lectures. In 1974, The Desert Sun announced that Gnagy would lead a new local series in the Coachella Valley titled How Do You Doodle. This project, five years in the making, showcased a technique Gnagy perfected to complete a color painting lesson in just 30 minutes.

Even as his public presence diminished, Gnagy’s influence endured. Art kits featuring his name remained popular through the 1980s and beyond, with some still available today. Figures like Andy Warhol credited Gnagy’s show as a formative influence, as did comic book artist Bernie Wrightson, renowned for his work on Swamp Thing and other horror series.

Gnagy passed away in 1981 at age 74 due to a heart attack (though some sources referred to it as cardiac arrest). Many who admired him recall his encouraging words as much as his artistic techniques, crediting him with inspiring their careers in art. In Gnagy’s philosophy, anyone could become an illustrator by mastering basic shapes like cubes and cylinders. As one of his art kit advertisements proclaimed, 'Who’s your favorite artist? It could be you.'