On the morning of August 21, 1986, a man traveling to Nyos, a village near a crater lake in northwest Cameroon, came across a horrifying sight: dozens of dead animals scattered along the road. Concerned, he stopped at a home to ask the residents what had happened, only to discover that the entire village was dead, despite showing no visible signs of injury.

Within days, authorities confirmed that over 1,700 people in Nyos had perished, along with thousands of animals. The cause of the disaster was initially unclear, but it seemed eerily similar to a tragedy that took place two years earlier, just 60 miles south.

On August 15, 1984, at Lake Monoun, villagers found 37 people and numerous animals dead along the lake's shore. At first, officials were puzzled and even speculated about domestic terrorism. Witnesses reported hearing rumbling noises and witnessing a strange white cloud rise from the lake before vanishing.

While the Lake Monoun tragedy left geologists and local authorities baffled, the catastrophe at Lake Nyos attracted global attention. Scientists from all over the world converged on Nyos to investigate the cause. Since the lake is located on a dormant volcano, the initial hypothesis was that a volcanic eruption released toxic gases into the atmosphere. However, further studies revealed a far stranger explanation.

The tragic events at both Lake Monoun and Lake Nyos were the result of an incredibly rare natural phenomenon known as limnic eruptions.

What Exactly Are Limnic Eruptions?

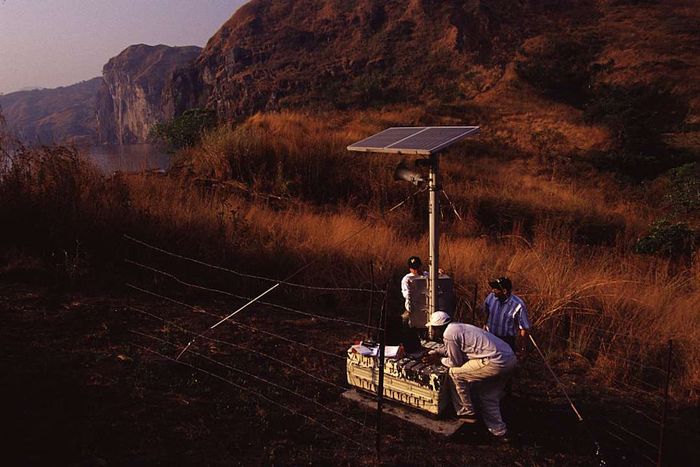

Scientists installed carbon dioxide detectors after the Nyos tragedy. | Louise Gubb/GettyImages

Scientists installed carbon dioxide detectors after the Nyos tragedy. | Louise Gubb/GettyImagesThe two occurrences in Cameroon are the only known cases of limnic eruptions. Despite their deadly and terrifying nature, these eruptions are extremely rare because they require a very specific set of circumstances—circumstances that were present at Lake Monoun and Lake Nyos during the 1980s.

A limnic eruption, also known as lake overturn, happens when carbon dioxide (CO2) dissolved in the deep waters of a lake suddenly erupts, forming a lethal gas cloud above the surface. Since carbon dioxide is denser than air, the cloud sinks toward the ground, suffocating animals, livestock, and humans.

Limnic eruptions take place in locations where the water holds a high concentration of carbon dioxide. This CO2 can form through various geological processes, with volcanic gases from Earth's magma being the most common source.

Carbon dioxide dissolves more easily in areas with high pressure, such as the cold, deep regions of lakes. As a result, deep lake bottoms can accumulate significant levels of CO2, which decreases toward the surface. Limnic eruptions are most likely to occur in stratified lakes, where water remains in layers that rarely mix, trapping the CO2 at the bottom as pressure builds.

Changes in temperature or pressure can trigger a rapid release of the accumulated carbon dioxide from a lake, leading to an eruption. Although the exact cause of the explosions at Lake Monoun and Lake Nyos is unclear, their proximity to the Oku Volcanic Field suggests that an earthquake or small volcanic eruption may have preceded each disaster. We may never know the exact trigger.

Preventing the Next Limnic Eruption

A fountain of carbon dioxide-rich water shoots up from the deep waters of Lake Nyos during the degassing process. | USGS // Public Domain

A fountain of carbon dioxide-rich water shoots up from the deep waters of Lake Nyos during the degassing process. | USGS // Public DomainAfter examining the chemical composition and geology surrounding Lake Monoun and Lake Nyos, experts concluded that the eruptions were caused by carbon dioxide accumulating in the cold bottom waters, where pressure gradually built up until the gases erupted violently, like a shaken soda can. Researchers began focusing on identifying other lakes with similar conditions that could trigger limnic eruptions and sought ways to prevent such disasters, with particular attention given to Lake Kivu, located on the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Lake Kivu, situated just south of the highly active Nyiragongo stratovolcano, contains large amounts of carbon dioxide that do not dissipate at the surface. These conditions make the lake vulnerable to a potential limnic eruption in the future. However, scientists now have an advantage, thanks to research carried out following the Lake Monoun and Lake Nyos disasters.

Beginning in 1992 at Lake Monoun and 1995 at Lake Nyos, researchers started experimenting with degassing techniques, a process that involves inserting a pipe into the CO2-rich layers of the lake to allow the water to jet out like a fountain, releasing the gas harmlessly into the air [PDF]. For these experiments, they used specialized tubes with sensors and control valves, which were anchored to floating rafts on the lakes. This setup enabled scientists to monitor the gradual and safe gas release, preventing an explosion.

Full-scale degassing operations commenced in 2001 at Lake Nyos and in 2003 at Lake Monoun. Additional pipes were installed a few years later at each lake, successfully reducing the CO2 levels in the water, which lowered the risk of catastrophic explosions in the future.

Scientists now have a clearer understanding of how large quantities of lethal gas accumulate in lakes and the potential for devastating limnic eruptions. Lakes Monoun and Nyos continue to serve as natural laboratories, helping to develop new methods and equipment for monitoring—and preventing—similar disasters.