On February 27, 1948, 160 boys and girls gathered at Corpus Christi Memorial Stadium, eagerly anticipating the moment the flames would ignite. Surrounding a towering stack of comic books—filled with superhero exploits, crime stories, and graphic horror—the children had been lured by a clever incentive: donate three comics and gain free entry to a local movie theater.

“We are not opposed to wholesome comics,” stated Reverend Peter Rinaldi of the Corpus Christi Church. “In fact, we support them. However, we stand firmly against those that corrupt young minds with crime narratives and suggestive imagery.”

This scene played out repeatedly across the nation, from small towns to bustling cities. Religious figures, parent associations, youth organizations, and local authorities, all alarmed by the rising sway of comics, orchestrated ceremonial bonfires for titles like Crime Does Not Pay and Tales From the Crypt. These events aimed to rally public support for eradicating the illustrated stories believed to be poisoning the minds of the youth.

Once the movie ended, the moment arrived. The mayor stepped forward, igniting the stack of comics. As the flames roared and the pages crackled, the children edged closer, drawn by the warmth. An onlooker noted that they “cheered enthusiastically” as the fire consumed the comics. The comic book had become the nation’s top adversary.

The Comic Controversy

Before the rise of television, streaming, or video games, millions of American children turned to comics for entertainment. Emerging in the 1930s as a way to compile comic strips, the medium truly took off with Superman’s debut in 1938. A wave of superheroes followed, their extraordinary abilities perfectly suited to the visual storytelling of comics. By the close of World War II, comic sales soared to tens of millions each month. Publishers such as National Comics Publications (later DC Comics), Timely (the future Marvel), and EC reaped substantial profits from this booming industry.

Adults quickly took notice of comics’ powerful hold on children, fearing that the more graphic and violent titles could harm young minds. Media reports amplified these concerns, linking comic book reading to juvenile delinquency. In one tragic case, 6-year-old Sammy from New Castle, Pennsylvania, shot and killed his 10-year-old brother George. A coroner’s inquest found Sammy’s comic book habit partly to blame. The Redwood City Tribune reported on a 13-year-old boy who “smothered” an 8-year-old girl over a comic book dispute, warning that this “comic book murder” would not be an isolated incident. In La Porte, Indiana, five burglars were said to have drawn criminal “ideas” from their comic book reading.

Even superheroes faced criticism. Some argued that characters like Batman and Superman, who operated outside the law, set a dangerous example by acting as vigilantes without accountability.

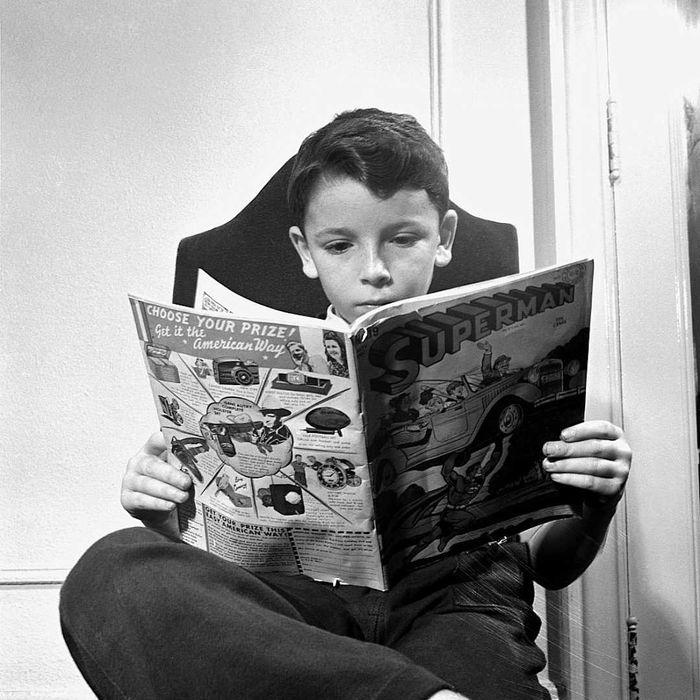

Superman's perceived authoritarian nature became a focal point of the anti-comics movement. | Historical/GettyImages

Superman's perceived authoritarian nature became a focal point of the anti-comics movement. | Historical/GettyImagesThe moral panic reached such heights that a divorced father in Chicago, Karl Drewes, was legally barred from allowing his children to read comics during his custody time. A judge mandated that Drewes keep his 8- and 12-year-old sons away from comics and gangster films, as their mother claimed the material made them “nervous.” (The judge also increased Drewes’ child support payments from $15 to $17 per week.)

Amid the uproar, a few rational voices emerged. In California, the Congress of Parents and Teachers (PTA) tasked Stanford graduate students with studying comic book reading habits to determine any connection to crime or reduced intelligence. The study found no such link, but this did little to calm public fears. By the time the 1947 study was completed, comic book burnings were already underway.

One of the earliest recorded burnings occurred in 1945, when students at SS Peter and Paul school in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, adhered to guidelines established by Reverend Robert Southard of Loyola University in Chicago. Southard categorized comics into three groups: harmless, questionable, and condemned. Harmless comics included Disney titles like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck; questionable ones featured Superman and Archie, the latter due to the character’s suggestive behavior; and condemned titles included Batman, Wonder Woman, and Suspense. Comics from the latter two categories were collected and burned. (The initial bonfire was postponed due to rain.)

These publicized events inspired similar actions across the country. Comic burnings were organized in cities like Buffalo, Memphis, Waterbury (Connecticut), Vallejo (California), and Louisville (Kentucky). In Rumson, New Jersey, Cub Scouts collected comics while standing on a fire truck. In Port Huron, Michigan, students from St. Stephen Catholic School sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the comics burned. In Freeport, Illinois, a Boy Scout troop held a bonfire supervised by the local assistant fire chief, who gave a fire safety talk while Little Lulu comics were consumed by flames.

One of the most memorable burnings occurred in 1948, when 13-year-old David Mace of Spencer, West Virginia, organized 600 students to denounce comic books. Supported by the local PTA, the event resembled a tent revival more than a simple bonfire, with Mace leading the children in a solemn pledge.

“We believe comic books harm the mind, body, and morals of young people, and so we vow to burn those in our possession,” Mace declared. “We also promise to avoid reading any more. Do you, my fellow students, agree that comic books have led to the ruin of many young readers?”

“We do,” the crowd replied in unison.

“Do you believe you will grow stronger by refusing to read comic books?”

“We do,” they affirmed.

“Then let us consign them to the flames,” Mace declared.

With those words, Mace and the crowd watched as roughly 2000 comics were consumed by fire. A newspaper columnist humorously noted that the boy’s eloquent speech was likely crafted by a PTA member or “a student with a sharp sense of humor.”

The Wertham Catalyst

Few people, however, saw the humor in such acts of censorship. Historically, book burnings have been linked to authoritarian regimes. (Notably, one comic book burning during this period took place in communist East Berlin.) There was scant evidence to prove that reading comics led to criminal behavior. (For instance, young Sammy Nail, who shot his brother, was also reportedly influenced by Western films prior to the incident.)

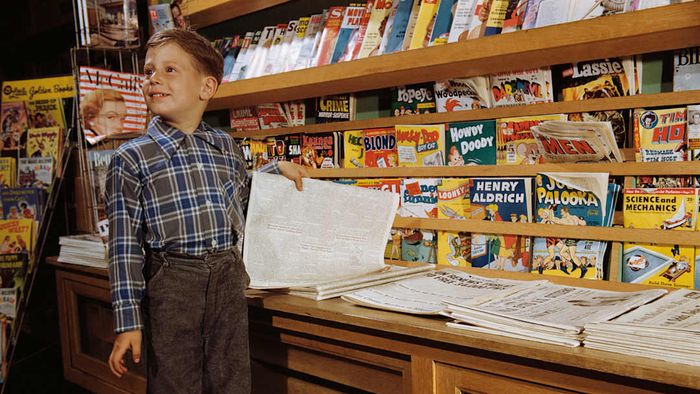

Titles like 'Lassie' and 'Blondie' are humorously accused of corrupting this young boy’s mind. | Steven Gottlieb/Corbis Historical via Getty Images

Titles like 'Lassie' and 'Blondie' are humorously accused of corrupting this young boy’s mind. | Steven Gottlieb/Corbis Historical via Getty ImagesA major factor behind the widespread acceptance of this theory was Dr. Frederic Wertham. A psychiatrist of German origin, Wertham had dedicated years to treating young patients at a psychiatric clinic in Harlem. His findings were highlighted in a 1948 issue of Collier’s magazine, where Wertham claimed that comics promoted delinquency and shaped sexual behavior. One of his most controversial statements was that Batman and his young companion, Robin, symbolized a homosexual fantasy, or “a dream of two gay men cohabiting.”

Wertham’s opinions resonated with those already opposed to comic books. However, the genre found a passionate advocate in 14-year-old David Wigransky, who stood as a kind of Superman against Wertham’s Lex Luthor. In a letter published in the intellectual Saturday Review of Literature, Wigransky challenged Wertham and other critics, denouncing censorship and implying that adults were overstepping their authority. (One critic noted that Wigransky, being well-read, was not the type of child they were concerned about.)

“Unlike other critics of comics, I have firsthand experience with them,” Wigransky wrote. He dismissed the 25 or so “delinquents” cited by Wertham out of an estimated 70 million comic readers. “Many of these delinquents happened to read comics, just like 69,999,975 perfectly healthy, happy, and normal Americans. It’s absurd to claim that 69,999,975 people are law-abiding because they read comics, just as it’s absurd to blame the 25 delinquents on their reading habits.”

Despite Wigransky’s noble efforts, the backlash against comics continued. Soon after his letter appeared, children in Binghamton, a small town in upstate New York, organized what became one of the most widely publicized comic burnings of the decade. A student committee went door-to-door, collecting comics for their bonfire. They even approached delis, drugstores, and shoe repair shops, urging owners to sign a “pledge” refusing to sell sensational comics, aiming to cut off the problem at its source. Stores that declined faced the threat of a boycott.

On the day of the event, children gathered around a kiln near a handball court at St. Patrick’s School. Classes were dismissed so students could witness the burning of over 2000 comics, singing the school’s alma mater as the flames rose. A photograph of the blaze was later featured in Time magazine, bringing national attention to the event.

“The publishers,” the student leader told a reporter, “are slowly improving their content and cleaning it up. Only time will reveal the extent of these changes.”

The Bonfire Dies Down

While the comic burnings were dramatic, the industry faced even greater challenges. In 1954, Senate hearings discussed the impact of crime and horror comics. EC Comics, in particular, was criticized for its graphic violence. Publisher William Gaines attempted to defend his work, arguing that a severed head was appropriate for a horror comic. His defense, however, fell flat.

Facing pressure, the comic industry chose self-regulation over government intervention. The Comics Code Authority (CCA) was established to curb immoral content, effectively removing what one newspaper called “filth.” Romance and superhero comics thrived, alongside titles like Lassie and Popeye. However, the rise of affordable television began to erode readership. Why settle for reading Superman when his adventures were now on TV?

Superman’s live-action TV series—and television in general—diverted attention from comic books. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Superman’s live-action TV series—and television in general—diverted attention from comic books. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesThe era of comic book burnings began to fade. In 1955, a Rhode Island Boy Scout troop canceled a planned burning after New York media criticized it as censorship. To avoid tarnishing the Scouts’ reputation, organizers abandoned the event.

Decades later, Wertham’s claims, though long disputed, were revealed to be based on biased research. In 2013, Carol Tilley, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science, published findings from Wertham’s personal archives at the Library of Congress. Tilley argued that Wertham exaggerated his data, citing interactions with hundreds of at-risk youth in Harlem, not thousands as he claimed. His theory about Batman and Robin as gay icons also contradicted the views of two gay teens he interviewed, one of whom expressed a preference for Tarzan.

While comic book burnings have fallen out of favor, censorship persists. Most notably, Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus, which recounts his family’s Holocaust experiences, was banned in 2022 and 2023 by school boards in Tennessee and Missouri due to its sexual content. (The minimal nudity in the book is far from provocative.) “It’s just another book … toss it onto the fire,” Spiegelman remarked. Though the flames have died down, the embers of censorship still smolder.