Key Takeaways

- Although Michelangelo is celebrated mainly for his sculpting, he also made significant strides in architecture. His projects, such as the tomb of Julius II, the San Lorenzo façade, and the Medici Chapel, were frequently left incomplete due to interruptions and alterations that strayed from his initial designs.

- Despite these challenges, Michelangelo's architectural projects reflect his deep commitment to design. Notable achievements include the unique window arrangement at the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi and the impressive staircase of the Laurentian Library.

- In his later years, Michelangelo took on pivotal commissions like the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome, demonstrating his influence on urban development and architectural creativity. He skillfully integrated his architectural ideas with pre-existing structures, crafting iconic examples of Renaissance architecture.

"I have never felt salvation in nature. I love cities above all." This statement by Michelangelo perfectly encapsulates his artistic philosophy. Unlike Leonardo Da Vinci, who drew inspiration from the natural world, Michelangelo sought to transcend it, a tendency that is particularly visible in his architectural works.

Michelangelo frequently asserted that his true calling was sculpture, denying any association with painting or architecture. However, his legacy confirms that he excelled in all three disciplines.

Before turning twenty-five, the artist's early sculptures had already achieved great acclaim across Europe. By his late thirties, under immense pressure, he created what is widely regarded as the most extraordinary and imaginative fresco painting in history: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo's architectural ventures, including the tomb of Julius II, the façade for San Lorenzo, and the Medici Chapel, were fraught with setbacks. Each project faced interruptions and alterations, leaving none fully realized as he had envisioned. Despite these challenges, his enthusiasm for innovation and design never waned. At sixty-five, he was still to undertake two of his most significant architectural commissions.

This article delves into some of Michelangelo's pivotal architectural achievements. Click the links below to uncover the stories behind these works and the tension between the artist's struggles and his belief in a divine purpose.

- Basilica di San Lorenzo: Pope Leo X commissioned Michelangelo to design a façade for the Basilica di San Lorenzo, but the project was abandoned four years later. Discover why Michelangelo's inaugural architectural endeavor remained unfinished.

- Palazzo Medici-Riccardi Windows: Michelangelo's window design for this palace remains one of the most iconic in history. Learn why it is famously referred to as a "kneeling window."

- Medici Chapel: Cardinal Guilio de' Medici tasked Michelangelo with constructing a modest chapel to serve as the burial site for the influential Medici family. Explore Michelangelo's complex relationship with the Medicis on this page.

- Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici: Visit this page to view one of the two tombs within the Medici Chapel and appreciate the magnificence Michelangelo bestowed upon the memory of these lesser-known dukes.

- Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici: The second tomb in the Medici Chapel honors Lorenzo the Magnificent, an early patron of Michelangelo until his death in 1492. Discover more about this remarkable work.

- Laurentian Library: Despite his strained relationship with the Medici family, Michelangelo began work on the Laurentian Library. Learn more about this ambitious architectural project.

- Study of Fortification for the Porta al Prato of Ognissanti: Michelangelo contributed to the design of fortifications for Rome during its conflict with the Florentine Medicis, though none of his structures survive today except in sketches. Explore his fortification designs further.

- Piazza del Campidoglio: Michelangelo was entrusted with revitalizing the grandeur of this piazza on the Capitoline Hill. Read about its layout, buildings, and sculptures.

- Marcus Aurelius Statue Base: The statue of the Roman emperor is the sole surviving bronze statue from antiquity. Learn about Michelangelo's design for the base of this priceless artifact.

- Farnese Palace Courtyard: Initially designed by Antonio da Sangallo, Michelangelo was called upon to complete the project after da Sangallo's death. See how he harmonized his design with the original architect's vision.

- Santa Maria degli Angeli: Michelangelo left this church unfinished, built on the remnants of the Roman Baths of Diocletian. Find out more about this unique undertaking.

Proceed to the next page to start your exploration of Michelangelo's architectural masterpieces with an in-depth look at the Basilica di San Lorenzo.

For further insights into Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, explore the following resources:

Basilica di San Lorenzo by Michelangelo

Located in Florence, Italy, the Basilica di San Lorenzo was the focus of Michelangelo's architectural efforts from 1516 to 1520, where he aimed to create a magnificent new design for the church.

Located in Florence, Italy, the Basilica di San Lorenzo was the focus of Michelangelo's architectural efforts from 1516 to 1520, where he aimed to create a magnificent new design for the church.In 1516, Pope Leo X commissioned Michelangelo to design an impressive façade for the Basilica of San Lorenzo. This project gained significance due to the growing influence of the Medici family and their pope, Leo X. Michelangelo returned to Florence to undertake this politically charged assignment for the Medici pope.

Michelangelo dedicated himself to the project, confidently stating that the façade would serve as a "mirror of architecture and sculpture for all of Italy." However, after three years of relentless effort, including numerous trips to Carrara and Seravezza to source the finest marble, the commission was abruptly canceled. The pope offered no explanation, leaving Michelangelo both enraged and deeply humiliated.

A likely explanation for the project's cancellation was the passing of Lorenzo de' Medici in 1519, the church's namesake and the primary advocate for the endeavor. Additionally, the Medici family shifted their focus to financing another family monument: a tomb chapel dedicated to two Medici dukes, Lorenzo and Giuliano (who died in 1516).

During his work on the Basilica di San Lorenzo, Michelangelo also managed to take on other projects for the Medici family. Discover more about his innovative window designs for the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in the next section.

For additional information on Michelangelo, art history, and other celebrated artists, explore the following resources:

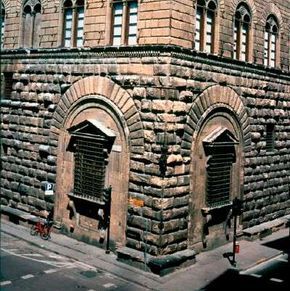

Palazzo Medici-Riccardi Windows by Michelangelo

Designed by Michelangelo in 1517, the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi windows are located in Florence, Italy, and remain a testament to his architectural ingenuity.

Designed by Michelangelo in 1517, the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi windows are located in Florence, Italy, and remain a testament to his architectural ingenuity.Michelangelo designed one of the most iconic window styles in history for the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi. These windows are famously referred to as kneeling windows due to the unique shape of their supporting consoles, which extend nearly to the ground, resembling a pair of legs.

During his time under the patronage of the Medici family, Michelangelo undertook several significant projects, including the Medici Chapel. He began work on this chapel just a few years after completing the windows for the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi. Continue to the next page for more details.

For further exploration of Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, refer to the following resources:

Medici Chapel by Michelangelo

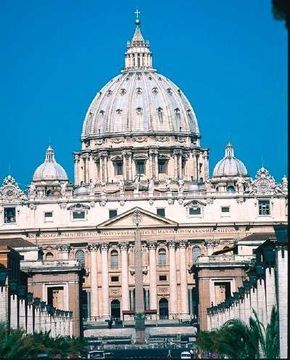

Michelangelo's dome for the Medici Chapel (1519-34) is located in San Lorenzo, Florence, and remains a remarkable architectural achievement.

Michelangelo's dome for the Medici Chapel (1519-34) is located in San Lorenzo, Florence, and remains a remarkable architectural achievement.Commissioned in 1519 by Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, Michelangelo's Medici Chapel was designed as a modest structure to serve as the burial site for Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici. It was intended to reflect the design of Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy for San Lorenzo, a Florentine masterpiece from the 1420s.

The dome of the Medici Chapel, with its coffered design, draws inspiration from the Roman Pantheon, though Michelangelo's version is notably lighter and more luminous. He meticulously planned the placement of the chapel's windows to ensure optimal lighting, which enhances the structure's atmosphere and purpose. The four circular elements at the dome's base further contribute to its uplifting and ethereal quality.

Inside the Medici Chapel, visitors can view Michelangelo's tomb for his former patron, Lorenzo de' Medici, created between 1520 and 1534.

Inside the Medici Chapel, visitors can view Michelangelo's tomb for his former patron, Lorenzo de' Medici, created between 1520 and 1534.As construction progressed, the scale of the figures Michelangelo envisioned for the Chapel grew significantly. These exquisitely crafted and polished sculptures are complemented by a striking two-tone background, featuring dark gray Tuscan limestone supports and white plaster walls, creating a harmonious yet dramatic contrast.

The Medici Chapel is richly decorated with intricate sculptures, Corinthian capitals, and fluted pilasters, showcasing Michelangelo's attention to detail and artistic mastery.

The Medici Chapel is richly decorated with intricate sculptures, Corinthian capitals, and fluted pilasters, showcasing Michelangelo's attention to detail and artistic mastery.Although incomplete, the Medici Chapel stands as the closest realization of Michelangelo's grand architectural and sculptural vision. After Michelangelo departed for Rome in 1534, never to revisit Florence, his students completed the installation of the chapel's sculptures. This perspective emphasizes the artist's sophisticated use of dark stone (pietra serena) and light-colored marble to articulate the chapel's architectural features.

Proceed to the next page for additional interior views of the Chapel and insights into the architectural design of Michelangelo's Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici.

For further exploration of Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, consult the following resources:

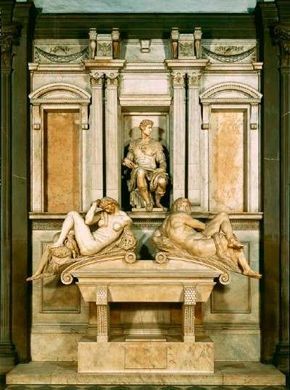

Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici Architecture by Michelangelo

Michelangelo's marble tomb for Giuliano de' Medici, measuring 20 feet 8 inches by 13 feet 9 inches, is housed within the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence.

Michelangelo's marble tomb for Giuliano de' Medici, measuring 20 feet 8 inches by 13 feet 9 inches, is housed within the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence.Constructed between 1520 and 1534, the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici features Michelangelo's transformation of the two lesser-known Medici dukes into grand allegorical figures. Rather than capturing their true likenesses, Michelangelo endowed them with heroic attributes, with Giuliano's statue prominently positioned above the representations of Night and Day.

As documented by a contemporary, Michelangelo expressed that he did not aim to depict the dukes "as nature had shaped them, but instead bestowed upon them a grandeur, proportion, and dignity...that he believed would earn them greater acclaim."

A detailed view of the console from Michelangelo's tomb of Giuliano de' Medici.

A detailed view of the console from Michelangelo's tomb of Giuliano de' Medici.Michelangelo's meticulous attention to detail is evident in the consoles supporting the reclining figures of the Times of Day. These elements showcase his adept use of fish-scale patterns and classical decorative moldings, reflecting his deep appreciation for ancient artistry.

Continue to the next page for further insights into the tombs of the two Medici dukes and to view images of the Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici.

For additional insights into Michelangelo, art history, and other celebrated artists, explore the following resources:

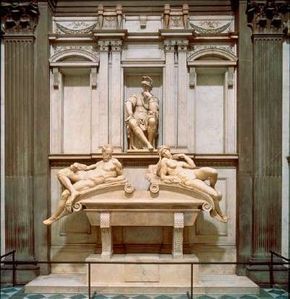

Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici Architecture by Michelangelo

The tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici, measuring 20 feet 8 inches by 13 feet 9 inches, is a majestic marble monument located within the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence.

The tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici, measuring 20 feet 8 inches by 13 feet 9 inches, is a majestic marble monument located within the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence.Michelangelo meticulously crafted distinct personalities for each of the two dukes. In Lorenzo de' Medici's tomb (1520-1534), Lorenzo is depicted as brooding and contemplative, with a closed posture and shadowed face (his statue is positioned above the figures of Dusk and Dawn). He is adorned in striking Roman armor that accentuates his muscular build. Together with the Times of Day, these figures reflect on the fleeting nature of time and the futility of earthly power.

During his work on the Medici Chapel, Michelangelo also undertook another project for the Medici family: the Laurentian Library. Continue to the next page to discover more about this architectural masterpiece.

For further exploration of Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, refer to the following resources:

Laurentian Library by Michelangelo

The vestibule and staircase of the Laurentian Library, designed by Michelangelo around 1524-34, are situated atop an existing monastery building in San Lorenzo, Florence.

The vestibule and staircase of the Laurentian Library, designed by Michelangelo around 1524-34, are situated atop an existing monastery building in San Lorenzo, Florence.Michelangelo undertook the Laurentian Library project concurrently with his work on the Medici Chapel. Built as an additional level above the monastery, the library's construction progressed in phases until Michelangelo left for Rome in 1534. Although he later provided a design for the grand staircase, he never witnessed the library in its completed form.

Commissioned by Giulio de' Medici, who had ascended to the papacy as Clement VII, the Laurentian Library was intended to house the extensive Medici book collection. The library's vestibule design, particularly its breathtaking staircase, stands as one of Michelangelo's most remarkable architectural accomplishments. Inspired by a dream, the staircase's three flowing flights appear almost animated as they descend, filling the vestibule with dynamic energy.

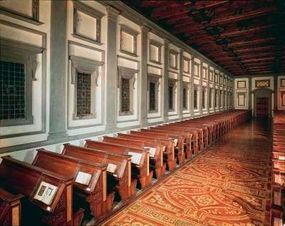

The reading room of the Laurentian Library.

The reading room of the Laurentian Library.Following the vibrant energy of the vestibule, the reading room offers a serene and focused atmosphere. The pilasters, ceiling beams, and floor design work in harmony to create a rhythmic repetition of bays that extend throughout the space, effectively anchoring the room's structure.

Wooden reading desks in the Laurentian Library.

Wooden reading desks in the Laurentian Library.Michelangelo meticulously designed the reading room's furniture to integrate seamlessly with the room's architectural aesthetic, ensuring a cohesive and unified design.

While the Laurentian Library was under construction, tensions arose between the Medicis and Rome. Having assisted in fortifying Rome, Michelangelo fell out of favor with the Medici family. Proceed to the next page to view a sketch Michelangelo created for a fortification.

For further insights into Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, explore the following resources:

Study of Fortification for the Porta al Prato of Ognissanti by Michelangelo

Michelangelo's study of fortification for the Porta al Prato of Ognissanti, measuring 16 x 22-1/8 inches, was created using pen and ink, watercolor, and red pencil. This work is housed at Casa Buonarroti in Florence.

Michelangelo's study of fortification for the Porta al Prato of Ognissanti, measuring 16 x 22-1/8 inches, was created using pen and ink, watercolor, and red pencil. This work is housed at Casa Buonarroti in Florence.This study by Michelangelo depicts a fortification for the Porta al Prato of Ognissanti, dating back to around 1529-30. Although none of Michelangelo's fortifications remain standing today, his surviving sketches highlight his engineering prowess. This expertise later proved invaluable when he designed the piers and dome of St. Peter's Basilica.

Michelangelo's next architectural project was of a more tranquil nature: the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome. Situated on the Capitoline Hill, this space was designed to evoke the grandeur of ancient Rome.

For additional information on Michelangelo, art history, and other celebrated artists, explore the following resources:

Piazza del Campidoglio by Michelangelo

Michelangelo was tasked with revitalizing Rome's Capitoline Hill. He achieved this by completely redesigning the Piazza del Campidoglio, including the plaza and its surrounding structures.

Michelangelo was tasked with revitalizing Rome's Capitoline Hill. He achieved this by completely redesigning the Piazza del Campidoglio, including the plaza and its surrounding structures.The Piazza del Campidoglio, initiated in 1538, was the outcome of Michelangelo's vision to restore the Capitoline Hill, a location of immense historical significance since ancient times.

The project began with the establishment of a central focal point, surrounded by three newly constructed or renovated buildings. At the heart of the oval courtyard stands a statue of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the sole surviving intact bronze statue from antiquity. Michelangelo designed the statue's base.

Piazza del Campidoglio pavement design (begun 1538).

Piazza del Campidoglio pavement design (begun 1538).Once in a state of disrepair after its medieval role as the headquarters for Roman guilds, the site required innovative solutions to transform it from ruins into the focal point of Roman socio-political life. Michelangelo embraced this challenge with enthusiasm, resulting in pioneering contributions to urban design. His radiant starburst pattern on the square amplified the dynamic relationship between the surrounding structures and the plaza's center.

A detailed view of Palazzo dei Senatori (begun 1538).

A detailed view of Palazzo dei Senatori (begun 1538).Michelangelo significantly restructured this building, which was mostly intact when the project commenced. By relocating its tower to a central position that aligned with the grand staircases leading to the entrance, he created a compelling contrast with the other two palazzos. Today, the building functions as Rome's city hall.

The Palazzo dei Conservatori is adorned with Corinthian pilasters.

The Palazzo dei Conservatori is adorned with Corinthian pilasters.Michelangelo redesigned the façade of the Palazzo dei Conservatori (begun 1538), which was mostly in ruins when he started transforming the square. The building exemplifies his use of a "giant Corinthian order," featuring massive pilasters on elevated bases that seamlessly connect the two levels. The flat roof and uniform entablature are hallmark elements of Michelangelo's architectural style.

A closer examination of the Palazzo dei Senatori staircase.

A closer examination of the Palazzo dei Senatori staircase.Where the two staircases of the Palazzo dei Senatori (begun 1538) converge, there is a niche housing a statue of the goddess Roma. Depicted seated triumphantly with a globe in her hand, she represents the expansive influence of Rome.

At the heart of Piazza del Campidoglio lies a bronze statue from ancient Rome. Discover how Michelangelo contributed to its enhancement on the following page.

For further insights into Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, explore the following resources:

- Michelangelo

Marcus Aurelius Statue Base by Michelangelo

The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, located in Piazza del Campidoglio, Rome, features a marble base crafted by Michelangelo.

The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, located in Piazza del Campidoglio, Rome, features a marble base crafted by Michelangelo.At the heart of the intricately designed Piazza del Campidoglio stands an equestrian statue of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the sole surviving bronze statue from antiquity that remains nearly intact. Michelangelo designed the statue's base. While the original statue has been relocated to the Capitoline Museum, the one in the piazza is a precise replica.

Similar to the Marcus Aurelius statue, the next page highlights a project that demonstrates Michelangelo's ability to harmoniously integrate his work with pre-existing structures, such as the Farnese Palace Courtyard.

For further exploration of Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, refer to the following resources:

- Michelangelo

Farnese Palace Courtyard by Michelangelo

Michelangelo was tasked with completing the courtyard of the Farnese Palace in Rome, Italy.

Michelangelo was tasked with completing the courtyard of the Farnese Palace in Rome, Italy.Michelangelo commenced work on the Farnese Palace courtyard in 1546. Following the death of Antonio da Sangallo in 1546, Pope Paul III appointed Michelangelo to oversee the project's final stages. Demonstrating his adaptability, Michelangelo seamlessly integrated his designs with the existing structure. For the courtyard and third-story façade, he designed windows that not only mirrored Sangallo's style but also enhanced and surpassed the original design. The palace, a square, freestanding stone edifice with a central courtyard, reflects the architectural trends of Florentine palazzi of the time.

The final structure in this article is the Santa Maria degli Angeli, another project where Michelangelo expanded upon an existing building. Continue to the next page for more details.

For further insights into Michelangelo, art history, and other renowned artists, explore the following resources:

- Michelangelo

Santa Maria degli Angeli by Michelangelo

Michelangelo began his work on Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome just a year before his death.

Michelangelo began his work on Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome just a year before his death.The project for Santa Maria degli Angeli (1563-64) was commissioned by Pope Pius IV and stands as one of Michelangelo's most unique assignments. It required converting the ruins of the Roman Baths of Diocletian, constructed in 305 A.D. as a hub of social and physical indulgence, into a Christian church. Originally, the vast interior was decorated with multicolored marble, painted stucco, and pagan statues. Michelangelo repurposed the central hall's immense space into the church's luminous and spacious transept. The project was finalized in 1564 by Jacopo LoDuca.

For additional insights into Michelangelo, art history, and other celebrated artists, explore the following resources:

- Michelangelo

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lauren Mitchell Ruehring is a freelance writer who has crafted promotional content for numerous artists, including Erté and Thomas McKnight. Her work has also appeared in publications like Kerry Hallam: Artistic Visions and Liudmila Kondakova: World of Enchantment. Additionally, she has been honored by the National Society of Arts and Letters.