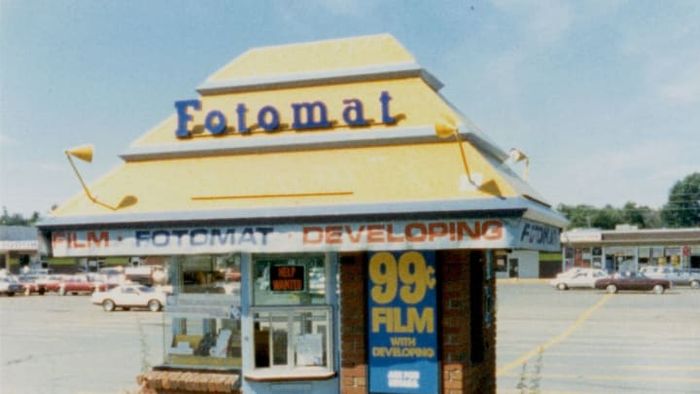

Much like McDonald's Golden Arches, the iconic golden pyramids of Fotomat stores became a recognizable symbol. Instead of fast food, these mini kiosks were dedicated to photography, offering small booths in parking lots, each staffed by a single employee. Men were called Fotomacs, while women were known as Fotomates. The dress code included hot pants, inspired by the attire worn by flight attendants at Pacific Southwest Airlines.

Customers would drive up to the Fotomat booth, drop off their film, and have it delivered by courier to a nearby lab for processing. The following day, it would be ready for pick-up. Aside from selling film and briefly experimenting with renting videotapes, this was the extent of Fotomat's services.

The idea, initially popularized by aviator Preston Fleet, was deceptively simple yet effective. At its peak in the 1970s and early 1980s, Fotomat boasted over 4000 locations across North America. Despite its minimal costs—these kiosks lacked even basic amenities like restrooms—and the widespread popularity of photography, Fotomat ultimately suffered due to its own overwhelming success. The company’s story even included a former president who became a federal fugitive.

During the 1960s, Kodak Instamatic cameras and film became a staple in American households. People would send in the familiar yellow film canisters filled with snapshots from weddings, birthdays, vacations, and other personal milestones, often waiting several days for the processed prints to be returned.

This is where Preston Fleet saw a business opportunity. Fleet, a wealthy aviation aficionado, was the son of Reuben Fleet, the founder of Consolidated Aircraft Company—later known as Convair—which produced planes during World War II. Born in Buffalo, New York, Fleet’s family relocated to San Diego when the aviation industry moved west. There, he met Clifford Graham, a La Jolla entrepreneur known for his various business ventures. Graham was also infamous for his gun-toting persona and dubious business dealings that led investors astray.

Fotomat, however, was no scam. The idea of a small kiosk where people could drop off and pick up film for overnight processing was first introduced in Florida by Charles Brown in 1965. After purchasing Brown's shares and securing a royalty deal, Fleet and Graham launched Fotomat Corporation in 1967, with Graham as president and Fleet as vice-president. The concept took off quickly, reaching 1800 locations within 18 months. Due to its color scheme, many mistakenly thought Kodak was behind the operation, which led to complaints and lawsuits from Kodak itself. (In response, Fotomat changed its design in 1970 to clear up the confusion.)

While it was easy to place a Fotomat hut in a parking lot, the challenges of operating a business surrounded by traffic became apparent. Residents from New Dorp on Staten Island shared memories on Facebook of accidents where cars accidentally collided with the kiosk. (In one memorable pop culture reference, terrorists destroy a Fotomat-like hut in the parking lot of Twin Pines Mall in the 1985 film Back to the Future.)

Then, there was the issue of bathrooms: they didn’t exist. Employees had to sneak into nearby supermarkets or other stores whenever nature called.

Despite the lack of restrooms and the infamous hot pants, Fotomat thrived to the point where Fleet and Graham decided to take the company public in 1969. At one point, each man’s stock was valued at $60 million. However, Graham’s controversial business tactics quickly caught up with him. In 1971, he was forced out of Fotomat amidst allegations of misusing company funds for personal gain, including his political ambitions—Graham was a backer of both Richard Nixon and Jack Kemp, the football player-turned-congressman who eventually became an assistant to the president and recommended fellow football pros as franchisees.

By the early 1980s, Fotomat had grown to over 4000 locations—though this expansion came at a price. Fleet, who had sold off his shares, and Graham, who was long gone, left Fotomat to grapple with overextension. The company often opened kiosks too close to each other, causing them to compete for the same customers. Additionally, pharmacies and grocery stores started to offer photo processing, adding to Fotomat’s troubles.

Fotomat booths were typically situated in parking lots. | David Prasad, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0

Fotomat booths were typically situated in parking lots. | David Prasad, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0However, the true downfall for Fotomat was not its rapid expansion—it was the rise of the one-hour minilab.

For an investment ranging from $50,000 to $100,000, existing stores could set up labs capable of processing photos in as little as one hour, allowing customers to shop while they waited. Minilabs surged from 600 locations in 1980 to 14,700 by 1988. Since film remained at the site, it was far less likely to get misplaced. This shift devastated Fotomat and similar businesses, causing Fotomat’s market share in photo processing to plummet from an impressive 18 percent to a mere 2 percent by 1988.

In an attempt to pivot, Fotomat tried diversifying, converting home movies to videotape and even offering VHS rentals during the 1980s VCR boom. However, these efforts failed. Mass layoffs and store closures followed, and eventually, minilabs would face their own challenges, particularly with the rise of 35mm and digital photography. By 1990, Fotomat had dwindled to just 800 locations.

Fleet, who had long departed from Fotomat—after the company was sold to Konica—was unaffected by its decline. Before his death in 1995, he authored a book, Hue and Cry, which questioned the authenticity of works attributed to William Shakespeare. Fleet also served as a founding director of the San Diego Aerospace Museum in 1963 and played a key role in popularizing Omnimax, an immersive theater experience under the Imax brand, installing the first Omnimax screen at the Reuben H. Fleet Space Theater and Space Museum in 1973.

Graham’s post-Fotomat life was far more colorful. He promoted a fraudulent gold mining operation called Au Magnetics, claiming he could transform sand into gold. Instead, he was accused of scamming investors. In 1986, a federal grand jury indicted him on charges of mail fraud, wire fraud, and tax evasion, but by then, Graham had vanished. He was never found, and some speculate he either evaded capture or was killed by an investor unhappy with his losses.

After Fotomat’s downfall, many of its former locations were repurposed for other businesses. Some became coffee shops, while others turned into watch repair kiosks, locksmith stands, windshield wiper dealers, or tailor shops. It’s safe to say that none of the new business owners required their employees to wear hot pants.